Уроборос

Уроборос — мифологический мировой змей, обвивающий кольцом Землю, ухватив себя за хвост; один из основных символов алхимии

Уроборос — мифологический мировой змей, обвивающий кольцом Землю, ухватив себя за хвост; один из основных символов алхимии

Уроборос — мифологический мировой змей, обвивающий кольцом Землю, ухватив себя за хвост; один из основных символов алхимии

Уроборос — мифологический мировой змей, обвивающий кольцом Землю, ухватив себя за хвост; один из основных символов алхимии

Уроборос — мифологический мировой змей, обвивающий кольцом Землю, ухватив себя за хвост; один из основных символов алхимии

Auroborus — вариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницей

Oroborus — вариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницей

Oureboros — вариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницей

Ouroboros — вариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницей

Uroboros — вариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницейвариант написания названия Уробороса латиницей

Οὐροβόρος — греческое написание названия Уробороса, от ουρά «хвост» и βορά, «еда, пища»; буквально «пожирающий [свой] хвост»греческое написание названия Уробороса, от ουρά «хвост» и βορά, «еда, пища»; буквально «пожирающий [свой] хвост»греческое написание названия Уробороса, от ουρά «хвост» и βορά, «еда, пища»; буквально «пожирающий [свой] хвост»греческое написание названия Уробороса, от ουρά «хвост» и βορά, «еда, пища»; буквально «пожирающий [свой] хвост»греческое написание названия Уробороса, от ουρά «хвост» и βορά, «еда, пища»; буквально «пожирающий [свой] хвост»

Змеи, кусающие свой собственный хвост, были обнаружены в египетских изображениях, датированных приблизительно 1600 годом до н.э. Затем такой змей появился у финикийцев и греков, которые назвали его уроборосом, что означает «пожирающий собственный хвост». «Таково техническое название этого чудовища, вошедшее затем в обиход алхимиков.

Самое впечатляющее его изображение дано в скандинавской космогонии. В прозаической, или Младшей, Эдде говорится, что Локи родил волка и змея. Оракул предупредил богов, что от этих существ будет земле погибель. Волка Френира привязали цепью, скованной из шести фантастических вещей: из шума шагов кота, из женской бороды, из корня скалы, из сухожилий медведя, из дыхания рыбы и из слюны птицы. Змея Иормунгандра «бросили в море, окружающее землю, и в море он так вырос, что и теперь окружает землю, кусая свой хвост». (1)

Также змея, кусающая свой хвост, есть и в индуизме, где дракон кружится перед черепахой, которая поддерживает четырех слонов, несущих на себе мир.

В символизме уроборос имеет несколько значений. Основной — отображение циклического характера Вселенной: создание из разрушения, Жизнь из Смерти. Уроборос ест собственный хвост, чтобы вновь обрести жизнь, в вечном цикле возобновления. На рисунке из книги алхимика Клеопатра, черная половина отображает в символической форме Ночь, Землю, и разрушительную силу природы, начало Инь; светлая половина представляет День, Небеса, порождающую творческую силу, начало Янь. Также в алхимии уроборос используется как глиф очищения.

ИсточникиКрыніцыŹródłaДжерелаSources

Дополнительная информацияДадатковая інфармацыяInformacja dodatkowaДодаткова інформаціяAdditional Information

Статус статьиСтатус артыкулаStatus artykułuСтатус статтіArticle status:

Заглушка (пустая страница, созданная чтобы застолбить неопределенно запланированную статью, либо чтобы прикрыть ведущую из другой статьи ссылку)

Подготовка статьиПадрыхтоўка артыкулаPrzygotowanie artykułuПідготовка статтіArticle by:

Адрес статьи в интернетеАдрас артыкулу ў інтэрнэцеAdres artykułu w internecieАдрес статті в інтернетіURL of article: //bestiary.us/uroboros

Культурно-географическая классификация существ:

Культурна-геаграфічная класіфікацыя істот:

Kulturalno-geograficzna klasyfikacja istot:

Культурно-географічна класифікація істот:

Cultural and geographical classification of creatures:

Псевдо-биологическая классификация существ:

Псеўда-біялагічная класіфікацыя істот:

Pseudo-biologiczna klasyfikacja istot:

Псевдо-біологічна класифікація істот:

Pseudo-biological classification of creatures:

Физиологическая классификация:

Фізіялагічная класіфікацыя:

Fizjologiczna klasyfikacja:

Фізіологічна класифікація:

Physiological classification:

Вымышленные / литературные миры:

Выдуманыя / літаратурныя сусветы:

Wymyślone / literackie światy:

Вигадані / літературні світи:

Fictional worlds:

Форумы:

Форумы:

Fora:

Форуми:

Forums:

- quote

Еще? Еще!

Апоп — великий змей египетской мифологии, враг верховного бога Ра и олицетворение мрака

Гаргулец — гад преогромный, дракон водный с шеею зело длиною, мордою вытянутою и буркалами, аки карбункулы светящимися

Василиск — тварь зело ужасная, взглядом жертв умерщвляющая, да воду дыханием зловонным отравляющая

Дракон — одно из наиболее распространенных вымышленных существ, встречающееся почти повсеместно, как правило — крылатый змей; общее название различных яшероподобных мифических существ

Ёрмунганд — мировой змей из скандинавской мифологии, средний сын Локи и Ангрбоды

Нидхегг — дракон из скандинавской мифологии, грызущий корни мирового дерева и грешников

Адские гончие — собирательное наименование демонических псовых в мифологии, фольклоре, фентези, играх

Нинки-нанка — в фольклоре народов Западной Африки огромные опасные змеи-оборотни, живущие в лесах и болотах и питающиеся отбившимися от племени детьми

Тиритчик — рептилиеподобное существо с маленькой головой и шестью ногами в фольклоре инуитов Аляски

Дябдар — в мифах эвенков гигантский змей

Ямата-но Ороти — легендарный японский дракон, гигантский змей с восемью головами и восемью хвостами

Куэлебре — в низшей мифологии Астурии и Кантабрии, опасный крылатый змей, охраняющий сокровища в своем логове в пещере у источника

Макупо — горный змееподобный дракон из фольклора жителей Западных Висайских островов Филиппинского архипелага

Эренсуге — согласно мифологии басков, змей с одной или с семью головами, воплощение необузданной силы

Керасты — в античности и средневековых европейских бестиариях рогатая гадюка

Лун — дальневосточный (в частности, китайский) дракон

Гидрус — в средневековых бестиариях, змея, заползающая спящим крокодилам в пасть, и разрывающая им внутренности

Якул — змея, стремительно бросающаяся на свою жертву

Фэйи — китайский змеевидный дракон, предвестник засухи

уроборос

-

1

Уроборос

General subject: ( the) Ouroboros

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Уроборос

-

2

уроборос

General subject: ( the) Ouroboros

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > уроборос

-

3

Уроборос

Универсальный русско-немецкий словарь > Уроборос

См. также в других словарях:

-

Уроборос — архаический образ, часто встречающийся в алхимических трактатах и представляющий собой змею, заглатывающую свой хвост. В рамках глубинной психологии, например у Э. Нойманна (Neumann E. Die Grosse Mutter , Zurich, 1956) трактуется как базовый… … Психологический словарь

-

уроборос — сущ., кол во синонимов: 2 • вымышленное существо (334) • символ (25) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

уроборос — Этимология. Мифологический персонаж, встречающийся в алхимических трактатах, в виде змеи, заглатывающей свой хвост. Исследования. В рамках глубинной психологии, например у Э.Нойманна трактуется как базовый архетип, символизирующий доисторическое… … Большая психологическая энциклопедия

-

Уроборос — Изображение уробороса в алхимическом трактате 1478 г. Автор Теодор Пелеканос Уроборос (др. греч … Википедия

-

УРОБОРОС — архаический образ, часто встречающийся в алхимических трактатах и представляющий собой змею, заглатывающую свой хвост. В рамках «глубинной» психологии, например у крупнейшего специалиста в этой области Э. Нойманна, трактуется как базовый архетип… … Символы, знаки, эмблемы. Энциклопедия

-

Уроборос — Изображается в виде змеи или дракона, пожирающего собственный хвост. Мой конец это мое начало. Символизирует отсутствие дифференциации, совокупность всего, изначальное единство, самодостаточность. Порождает сам. себя, сам с собой соединяется в… … Словарь символов

-

УРОБОРОС — (Uroboros) универсальный мотив змеи, свернувшейся в кольцо и кусающей свой собственный хвост.Как символ уроборос предполагает первичное состояние, подразумевающее темноту и саморазрушение, равно как и плодородность, и творческую потенцию. Он… … Словарь по аналитической психологии

-

уроборос — (грч. ura опашка, boros јадач) позната фигура од старогрчката митологија што прикажува змија што сама си ја јаде опашката и така се врти како круг симбол на вечноста … Macedonian dictionary

-

Ороборос — Уроборос. Изображение из алхимического трактата XV века Aurora Consurgens Уроборос, ороборос (от греч. ουρά, «хвост» и греч. βορά, «еда, пища»; букв. «пожирающий [свой] хвост») мифологический мировой змей, обвивающий кольцом Землю, ухватив себя… … Википедия

-

Уроборус — Уроборос. Изображение из алхимического трактата XV века Aurora Consurgens Уроборос, ороборос (от греч. ουρά, «хвост» и греч. βορά, «еда, пища»; букв. «пожирающий [свой] хвост») мифологический мировой змей, обвивающий кольцом Землю, ухватив себя… … Википедия

-

Цикличность в религии — Уроборос … Википедия

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An ouroboros in a 1478 drawing in an alchemical tract[1]

The ouroboros or uroboros ([2]) is an ancient symbol depicting a serpent or dragon[3] eating its own tail. The ouroboros entered Western tradition via ancient Egyptian iconography and the Greek magical tradition. It was adopted as a symbol in Gnosticism and Hermeticism and most notably in alchemy. The term derives from Ancient Greek οὐροβόρος,[4] from οὐρo oura ‘tail’ plus -βορός -boros ‘-eating’.[5][6] The ouroboros is often interpreted as a symbol for eternal cyclic renewal or a cycle of life, death, and rebirth; the snake’s skin-sloughing symbolises the transmigration of souls. The snake biting its own tail is a fertility symbol in some religions: the tail is a phallic symbol and the mouth is a yonic or womb-like symbol.[7]

Some snakes, such as rat snakes, have been known to consume themselves. One captive snake attempted to consume itself twice, dying in the second attempt. Another wild rat snake was found having swallowed about two-thirds of its body.[8]

Historical representations[edit]

First known representation of the ouroboros, on one of the shrines enclosing the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun

Ancient Egypt[edit]

One of the earliest known ouroboros motifs is found in the Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld, an ancient Egyptian funerary text in KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun, in the 14th century BCE. The text concerns the actions of the Ra and his union with Osiris in the underworld. The ouroboros is depicted twice on the figure: holding their tails in their mouths, one encircling the head and upper chest, the other surrounding the feet of a large figure, which may represent the unified Ra-Osiris (Osiris born again as Ra). Both serpents are manifestations of the deity Mehen, who in other funerary texts protects Ra in his underworld journey. The whole divine figure represents the beginning and the end of time.[9]

Ouroboros swallowing its tail; based on Moskowitz’s symbol for the constellation Draco

The ouroboros appears elsewhere in Egyptian sources, where, like many Egyptian serpent deities, it represents the formless disorder that surrounds the orderly world and is involved in that world’s periodic renewal.[10] The symbol persisted from Egyptian into Roman times, when it frequently appeared on magical talismans, sometimes in combination with other magical emblems.[11] The 4th-century CE Latin commentator Servius was aware of the Egyptian use of the symbol, noting that the image of a snake biting its tail represents the cyclical nature of the year.[12]

China[edit]

An early example of an ouroboros (as a purely artistic representation) was discovered in China, on a piece of pottery in the Yellow River basin. The jar belonged to the neolithic Yangshao culture which occupied the area along the basin from 5000 to 3000 BCE.[13]

Gnosticism and alchemy[edit]

In Gnosticism, a serpent biting its tail symbolised eternity and the soul of the world.[14] The Gnostic Pistis Sophia (c. 400 CE) describes the ouroboros as a twelve-part dragon surrounding the world with its tail in its mouth.[15]

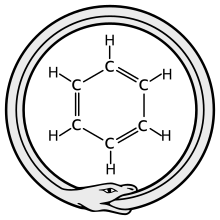

The famous ouroboros drawing from the early alchemical text, The Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra (Κλεοπάτρας χρυσοποιία), probably originally dating to the 3rd century Alexandria, but first known in a 10th-century copy, encloses the words hen to pan (ἓν τὸ πᾶν), «the all is one». Its black and white halves may perhaps represent a Gnostic duality of existence, analogous to the Taoist yin and yang symbol.[16] The chrysopoeia ouroboros of Cleopatra the Alchemist is one of the oldest images of the ouroboros to be linked with the legendary opus of the alchemists, the philosopher’s stone.[citation needed]

A 15th-century alchemical manuscript, The Aurora Consurgens, features the ouroboros, where it is used among symbols of the sun, moon, and mercury.[17]

-

A highly stylised ouroboros from The Book of Kells, an illuminated Gospel Book (c. 800 CE)

-

An engraving of a woman holding an ouroboros in Michael Ranft’s 1734 treatise on vampires

World serpent in mythology[edit]

In Norse mythology, the ouroboros appears as the serpent Jörmungandr, one of the three children of Loki and Angrboda, which grew so large that it could encircle the world and grasp its tail in its teeth. In the legends of Ragnar Lodbrok, such as Ragnarssona þáttr, the Geatish king Herraud gives a small lindworm as a gift to his daughter Þóra Town-Hart after which it grows into a large serpent which encircles the girl’s bower and bites itself in the tail. The serpent is slain by Ragnar Lodbrok who marries Þóra. Ragnar later has a son with another woman named Kráka and this son is born with the image of a white snake in one eye. This snake encircled the iris and bit itself in the tail, and the son was named Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye.[19]

It is a common belief among indigenous people of the tropical lowlands of South America that waters at the edge of the world-disc are encircled by a snake, often an anaconda, biting its own tail.[20]

The ouroboros has certain features in common with the Biblical Leviathan. According to the Zohar, the Leviathan is a singular creature with no mate, «its tail is placed in its mouth», while Rashi on Baba Batra 74b describes it as «twisting around and encompassing the entire world». The identification appears to go back as far as the poems of Kalir in the 6th–7th centuries.[citation needed]

The Ouroboros as an auroral Phenomenon[edit]

Following an exhaustive survey, historical linguist Marinus van der Sluijs and plasma physicist Anthony Peratt suggested that the ouroboros has a specific origin in time, in the 5th or 4th millennium BCE,[21][22] and was ultimately based on globally independent observations of an intense aurora, with somewhat different characteristics than the familiar aurora.[23] Specifically, the ouroboros could have represented an auroral oval seen as a whole, at a time when it was smaller and located closer to the equator than now. That could have been the case during geomagnetic excursions, when the geomagnetic field weakens and the earth’s magnetic poles shift places.[24] Tok Thompson and Gregory Allen Schrempp cautiously allow that this new idea might «mark a bold new interdisciplinary venture made possible by modern science«.[25]

Connection to Indian thought[edit]

In the Aitareya Brahmana, a Vedic text of the early 1st millennium BCE, the nature of the Vedic rituals is compared to «a snake biting its own tail.»[26]

Ouroboros symbolism has been used to describe the Kundalini.[27] According to the medieval Yoga-kundalini Upanishad: «The divine power, Kundalini, shines like the stem of a young lotus; like a snake, coiled round upon herself she holds her tail in her mouth and lies resting half asleep as the base of the body» (1.82).[28]

Storl (2004) also refers to the ouroboros image in reference to the «cycle of samsara».[29]

Modern references[edit]

Jungian psychology[edit]

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung saw the ouroboros as an archetype and the basic mandala of alchemy. Jung also defined the relationship of the ouroboros to alchemy: Carl Jung, Collected Works, Vol. 14 para. 513.

The alchemists, who in their own way knew more about the nature of the individuation process than we moderns do, expressed this paradox through the symbol of the Ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail. The Ouroboros has been said to have a meaning of infinity or wholeness. In the age-old image of the Ouroboros lies the thought of devouring oneself and turning oneself into a circulatory process, for it was clear to the more astute alchemists that the prima materia of the art was man himself. The Ouroboros is a dramatic symbol for the integration and assimilation of the opposite, i.e. of the shadow. This ‘feedback’ process is at the same time a symbol of immortality since it is said of the Ouroboros that he slays himself and brings himself to life, fertilizes himself, and gives birth to himself. He symbolizes the One, who proceeds from the clash of opposites, and he, therefore, constitutes the secret of the prima materia which … unquestionably stems from man’s unconscious.

The Jungian psychologist Erich Neumann writes of it as a representation of the pre-ego «dawn state», depicting the undifferentiated infancy experience of both humankind and the individual child.[30]

Kekulé’s dream[edit]

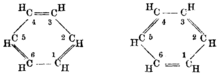

The ouroboros, Kekulé’s inspiration for the structure of benzene

Kekulé’s proposal for the structure of benzene (1872)

The German organic chemist August Kekulé described the eureka moment when he realised the structure of benzene, after he saw a vision of Ouroboros:[31]

I was sitting, writing at my text-book; but the work did not progress; my thoughts were elsewhere. I turned my chair to the fire and dozed. Again the atoms were gamboling before my eyes. This time the smaller groups kept modestly in the background. My mental eye, rendered more acute by the repeated visions of the kind, could now distinguish larger structures of manifold conformation: long rows, sometimes more closely fitted together; all twining and twisting in snake-like motion. But look! What was that? One of the snakes had seized hold of its own tail, and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. As if by a flash of lightning I awoke; and this time also I spent the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis.

Cosmos[edit]

Martin Rees used the ouroboros to illustrate the various scales of the universe, ranging from 10−20 cm (subatomic) at the tail, up to 1025 cm (supragalactic) at the head.[32] Rees stressed «the intimate links between the microworld and the cosmos, symbolised by the ouraborus«,[33] as tail and head meet to complete the circle.

Cybernetics[edit]

Cybernetics deployed circular logics of causal action in the core concept of feedback in the directive and purposeful behaviour in human and living organisms, groups, and self-regulating machines. The general principle of feedback describes a circuit (electronic, social, biological, or otherwise) in which the output or result is a signal that influences the input or causal agent through its response to the new situation. W. Ross Ashby applied ideas from biology to his own work as a psychiatrist in «Design for a Brain» (1952): that living things maintain essential variables of the body within critical limits with the brain as a regulator of the necessary feedback loops. Parmar contextualises his practices as an artist in applying the cybernetic Ouroboros principle to musical improvisation.[34]

Hence the snake eating its tail is an accepted image or metaphor in the autopoietic calculus for self-reference,[35] or self-indication, the logical processual notation for analysing and explaining self-producing autonomous systems and «the riddle of the living», developed by Francisco Varela. Reichel describes this as:

…an abstract concept of a system whose structure is maintained through the self-production of and through that structure. In the words of

Kauffman, is ‘the ancient mythological symbol of the worm ouroboros embedded in a mathematical, non-numerical calculus.[36][37]

The calculus derives from the confluence of the cybernetic logic of feedback, the sub-disciplines of autopoiesis developed by Varela and Humberto Maturana, and calculus of indications of George Spencer Brown. In another related biological application:

It is remarkable, that Rosen’s insight, that metabolism is just a mapping…, which may be too cursory for a biologist, turns out to show us the way to construct recursively, by a limiting process, solutions of the self-referential Ouroborus equation f(f) = f, for an unknown function f, a way that mathematicians had not imagined before Rosen.[38][39]

Second-order cybernetics, or the cybernetics of cybernetics, applies the principle of self-referentiality, or the participation of the observer in the observed, to explore observer involvement in all behaviour and the praxis of science[40] including D.J. Stewart’s domain of «observer valued imparities».[41]

Armadillo girdled lizard[edit]

The genus of the armadillo girdled lizard, Ouroborus cataphractus, takes its name from the animal’s defensive posture: curling into a ball and holding its own tail in its mouth.[42]

Pescadillas are often presented biting their tails.

In Iberian culture[edit]

A medium-sized European hake, known in Spanish as pescadilla and in Portuguese as pescada, is often presented with its mouth biting its tail. In Spanish it receives the name of pescadilla de rosca («torus hake»).[43]. Both expressions Uma pescadinha de rabo na boca «tail-in mouth little hake» and La pescadilla que se muerde la cola, «the hake that bites its tail», are proverbial Portuguese and Spanish expressions for circular reasoning and vicious circles.[44]

Dragon Gate Pro-Wrestling[edit]

The Kobe, Japan-based Dragon Gate Pro-Wrestling promotion used a stylised ouroboros as their logo for the first 20 years of the company’s existence. The logo is a silhouetted dragon twisted into the shape of an infinity symbol, devouring its own tail. In 2019, the promotion dropped the infinity dragon logo in favour of a shield logo.

In fiction[edit]

«Ouroboros» is an episode of the British science-fiction sitcom Red Dwarf,[45] in which one character is revealed to be his own father due to time travel. The concept also features in Claire North’s ‘the fifteen lives of Harry August.

The Worm Ouroboros is a high-fantasy novel written by E. R. Eddison. Much like the cyclical symbol of the ouroboros eating its own tail, the novel ends the way it begins.

The Ouroboros is used as a main plot device in Lisa Maxwell’s The Last Magician series.

The main six playable characters of the video game Xenoblade Chronicles 3 are able to transform into fiercely powerful forms called Ouroboros, which are ultimately tied to the fate of their world.[46]

The Ouroboros is the adopted symbol of the End Times-obsessed Millennium Group in the TV series Millennium. It also briefly appears when Dana Scully gets a tattoo of it in The X-Files episode «Never Again».

The Ouroboros is referenced in the science fiction short story All You Zombies by American writer Robert A. Heinlein as ‘the worm Ouroboros, the world snake’. The short story later serves as inspiration for the movie Predestination (2014).

In the A Discovery of Witches novels and television adaptation, the crest of the de Clermont family is an ouroboros. The symbol plays a significant role in the alchemical plot of the story.

In The Wheel of Time, the Aes Sedai wear a «Great Serpent» ring, described as a snake consuming its own tale. This image evokes the idea of eternity, and the cyclical nature of time and creation (major themes of the series, throughout).

Splatoon 3 has a similar creature called the Horrorboros which is based off the ouroboros.

See also[edit]

- Amphisbaena

- Cyclic model

- Dragon (M. C. Escher)

- Endless knot

- Ensō

- Eternal return (Eliade)

- Eternalism (philosophy of time)

- Historic recurrence

- Hoop snake

- Infinite loop

- Möbius strip

- Quine (computing)

- Self-reference

- Social cycle theory

- Strange loop

- Three hares

- Valknut

- The Worm Ouroboros

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Theodoros Pelecanos’s manuscript of an alchemical tract attributed to Synesius, in Codex Parisinus graecus 2327 in the Bibliothèque Nationale, France, mentioned s.v. ‘alchemy’, The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0199545561

- ^ «uroboros». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019.

- ^ «Salvador Dalí: Alchimie des Philosophes | The Ouroboros». Academic Commons. Willamette University.

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1940), οὐροβόρος

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1940), οὐρά

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1940), βορά

- ^ Arien Mack (1999). Humans and Other Animals. Ohio State University Press. p. 359.

- ^ Mattison, Chris (2007). The New Encyclopedia of Snakes. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-691-13295-2.

- ^ Hornung, Erik. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Cornell University Press, 1999. pp. 38, 77–78

- ^ Hornung, Erik (1982). Conceptions of God in Egypt: The One and the Many. Cornell University Press. pp. 163–64.

- ^ Hornung 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Servius, note to Aeneid 5.85: «according to the Egyptians, before the invention of the alphabet the year was symbolized by a picture, a serpent biting its own tail because it recurs on itself» (annus secundum Aegyptios indicabatur ante inventas litteras picto dracone caudam suam mordente, quia in se recurrit), as cited by Danuta Shanzer, A Philosophical and Literary Commentary on Martianus Capella’s De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii Book 1 (University of California Press, 1986), p. 159.

- ^ van der Sluijs, Marinus Anthony; Peratt, Anthony L. (2009). «The Ourobóros as an Auroral Phenomenon». Journal of Folklore Research. 46 (1): 3–41. doi:10.2979/JFR.2009.46.1.3. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 40206938. S2CID 162226473.

- ^ Origen, Contra Celsum 6.25.

- ^ Hornung 2002, p. 76.

- ^ Eliade, Mircea (1976). Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashions. Chicago and London: U of Chicago Press. pp. 55, 93–113.

- ^ Bekhrad, Joobin. «The ancient symbol that spanned millennia». BBC. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Lambsprinck: De Lapide Philosophico. E Germanico versu Latine redditus, per Nicolaum Barnaudum Delphinatem …. Sumptibus LUCAE JENNISSI, Frankfurt 1625, p. 17.

- ^ Jurich, Marilyn (1998). Scheherazade’s Sisters: Trickster Heroines and Their Stories in World Literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29724-3.

- ^ Roe, Peter (1986), The Cosmic Zygote, Rutgers University Press

- ^ Daily, Charles (2022). The Serpent Symbol in Tradition. Google Books. pp. 218–219.

- ^ Daily, Charles (24 January 2022). The Serpent Symbol in Tradition. Books Google. ISBN 9781914208690.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Marinus Anthony van der Sluijs and Anthony L. Peratt (2009). «The Ouroboros as an Auroral Phenomenon». Folklore Research 46, No. 1: 17.

- ^ van der Sluijs, Marinus Anthony (2021). The Earth’s Aurora. Vancouver: All-Round Publications. pp. 99, 102, 216.

- ^ Tok Thompson, Gregory Allen Schrempp (2020). The Truth of Myth: World Mythologies in Theory and Everyday Life. UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 157–159. ISBN 9780190222789.

- ^ Witzel, M., «The Development of the Vedic Canon and its Schools: The Social and Political Milieu» in Witzel, Michael (ed.) (1997), Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts. New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas, Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora vol. 2, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 325 footnote 346

- ^ Henneberg, Maciej; Saniotis, Arthur (24 March 2016). The Dynamic Human. Bentham Science Publishers. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-68108-235-6.

- ^ Mahony, William K. (1 January 1998). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. SUNY Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-7914-3579-3.

- ^ «When Shakti is united with Shiva, she is a radiant, gentle goddess; but when she is separated from him, she turns into a terrible, destructive fury. She is the endless Ouroboros, the dragon biting its own tail, symbolizing the cycle of samsara.» Storl, Wolf-Dieter (2004). Shiva: The Wild God of Power and Ecstasy. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-59477-780-6.

- ^ Neumann, Erich. (1995). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Bollington series XLII: Princeton University Press. Originally published in German in 1949.

- ^ Read, John (1957). From Alchemy to Chemistry. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-486-28690-7.

- ^ M Rees Just Six Numbers (London 1999) p. 7-8

- ^ M Rees Just Six Numbers (London 1999) p. 161

- ^ Parmar, Robin. «No Input Software: Cybernetics, Improvisation, and the Machinic Phylum.» ISSTA 2011 (2014). He further discusses the cybernetics in elementary actions (like picking up a drum stick), the evolution of cybernetic science from Norbert Wiener to Gordon Pask, Heinz von Foerster, and Autopoiesis, and in related fields such as Autocatalysis, the philosophical system of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, and Manuel DeLanda.

- ^ Varela, Francisco J. «A Calculus for Self-reference.» International Journal of General Systems 2 (1975): 5–24.

- ^ Kauffman sub-reference: Kauffman LH. 2002. Laws of form and form dynamics. Cybernetics & Human Knowing 9(2): 49–63, pp57–58.

- ^ Reichel, André (2011). «Snakes all the Way Down: Varela’s Calculus for Self-Reference and the Praxis of Paradis» (PDF). Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 28 (6): 646–662. doi:10.1002/sres.1105. S2CID 16051196.

- ^ Gutiérrez, Claudio, Sebastián Jaramillo, and Jorge Soto-Andrade. «Some Thoughts on A.H. Louie’s More Than Life Itself: A Reflection on Formal Systems and Biology.» Axiomathes 21, no. 3 (2011): 439–454, p448.

- ^ Soto-Andrade, Jorge, Sebastia Jaramillo, Claudio Gutierrez, and Juan-Carlos Letelier. «Ouroboros Avatars: A Mathematical Exploration of Self-reference and Metabolic Closure.» «One of the most important characteristics observed in metabolic networks is that they produce themselves. This intuition, already advanced by the theories of Autopoiesis and (M,R)-systems, can be mathematically framed in a weird-looking equation, full of implications and potentialities: f(f) = f. This equation (here referred to as Ouroboros equation), arises in apparently dissimilar contexts, like Robert Rosen’s synthetic view of metabolism, hyper set theory and, importantly, untyped lambda calculus. …We envision that the ideas behind this equation, a unique kind of mathematical concept, initially found in biology, would play an important role in the development of a true systemic theoretical biology. MIT Press online.

- ^ Müller, K H. Second-order Science: The Revolution of Scientific Structures. Complexity, design, society. Edition Echoraum, 2016.

- ^ Scott, Bernard. «The Cybernetics of Systems of Belief.» Kybernetes: The International Journal of Systems & Cybernetics 29, no. 7-8 (2000): 995–998.

- ^ Stanley, Edward L.; Bauer, Aaron M.; Jackman, Todd R.; Branch, William R.; Mouton, P. Le Fras N. (2011). «Between a rock and a hard polytomy: Rapid radiation in the rupicolous girdled lizards (Squamata: Cordylidae)». Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 58 (1): 53–70. (Ouroborus cataphractus, new combination).

- ^ Spínola Bruzón, Carlos. «Pescadilla; entre pijota y pescada.- Grupo Gastronómico Gaditano». grupogastronomicogaditano.com (in European Spanish). Grupo Gastronómico Gaditano. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

La pescadilla se fríe en forma de rosca, de modo que la cola esté cogida por los dientes del pez.

- ^ «pescadilla». Diccionario de la lengua española (in Spanish) (24th ed.). RAE-ASALE. 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ «Ouroboros». Red Dwarf: The Official Site. Grant Naylor Productions. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ «Xenoblade Chronicles 3 Direct – Nintendo Switch». Nintendo of America. 22 June 2022 – via YouTube.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bayley, Harold S (1909). New Light on the Renaissance. Kessinger. Reference pages hosted by the University of Pennsylvania

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Hornung, Erik (2002). The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. Cornell University Press.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press – via perseus.tufts.edu.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ouroboros.

- BBC Culture – The ancient symbol that spanned millennia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

An ouroboros in a 1478 drawing in an alchemical tract[1]

The ouroboros or uroboros ([2]) is an ancient symbol depicting a serpent or dragon[3] eating its own tail. The ouroboros entered Western tradition via ancient Egyptian iconography and the Greek magical tradition. It was adopted as a symbol in Gnosticism and Hermeticism and most notably in alchemy. The term derives from Ancient Greek οὐροβόρος,[4] from οὐρo oura ‘tail’ plus -βορός -boros ‘-eating’.[5][6] The ouroboros is often interpreted as a symbol for eternal cyclic renewal or a cycle of life, death, and rebirth; the snake’s skin-sloughing symbolises the transmigration of souls. The snake biting its own tail is a fertility symbol in some religions: the tail is a phallic symbol and the mouth is a yonic or womb-like symbol.[7]

Some snakes, such as rat snakes, have been known to consume themselves. One captive snake attempted to consume itself twice, dying in the second attempt. Another wild rat snake was found having swallowed about two-thirds of its body.[8]

Historical representations[edit]

First known representation of the ouroboros, on one of the shrines enclosing the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun

Ancient Egypt[edit]

One of the earliest known ouroboros motifs is found in the Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld, an ancient Egyptian funerary text in KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun, in the 14th century BCE. The text concerns the actions of the Ra and his union with Osiris in the underworld. The ouroboros is depicted twice on the figure: holding their tails in their mouths, one encircling the head and upper chest, the other surrounding the feet of a large figure, which may represent the unified Ra-Osiris (Osiris born again as Ra). Both serpents are manifestations of the deity Mehen, who in other funerary texts protects Ra in his underworld journey. The whole divine figure represents the beginning and the end of time.[9]

Ouroboros swallowing its tail; based on Moskowitz’s symbol for the constellation Draco

The ouroboros appears elsewhere in Egyptian sources, where, like many Egyptian serpent deities, it represents the formless disorder that surrounds the orderly world and is involved in that world’s periodic renewal.[10] The symbol persisted from Egyptian into Roman times, when it frequently appeared on magical talismans, sometimes in combination with other magical emblems.[11] The 4th-century CE Latin commentator Servius was aware of the Egyptian use of the symbol, noting that the image of a snake biting its tail represents the cyclical nature of the year.[12]

China[edit]

An early example of an ouroboros (as a purely artistic representation) was discovered in China, on a piece of pottery in the Yellow River basin. The jar belonged to the neolithic Yangshao culture which occupied the area along the basin from 5000 to 3000 BCE.[13]

Gnosticism and alchemy[edit]

In Gnosticism, a serpent biting its tail symbolised eternity and the soul of the world.[14] The Gnostic Pistis Sophia (c. 400 CE) describes the ouroboros as a twelve-part dragon surrounding the world with its tail in its mouth.[15]

The famous ouroboros drawing from the early alchemical text, The Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra (Κλεοπάτρας χρυσοποιία), probably originally dating to the 3rd century Alexandria, but first known in a 10th-century copy, encloses the words hen to pan (ἓν τὸ πᾶν), «the all is one». Its black and white halves may perhaps represent a Gnostic duality of existence, analogous to the Taoist yin and yang symbol.[16] The chrysopoeia ouroboros of Cleopatra the Alchemist is one of the oldest images of the ouroboros to be linked with the legendary opus of the alchemists, the philosopher’s stone.[citation needed]

A 15th-century alchemical manuscript, The Aurora Consurgens, features the ouroboros, where it is used among symbols of the sun, moon, and mercury.[17]

-

A highly stylised ouroboros from The Book of Kells, an illuminated Gospel Book (c. 800 CE)

-

An engraving of a woman holding an ouroboros in Michael Ranft’s 1734 treatise on vampires

World serpent in mythology[edit]

In Norse mythology, the ouroboros appears as the serpent Jörmungandr, one of the three children of Loki and Angrboda, which grew so large that it could encircle the world and grasp its tail in its teeth. In the legends of Ragnar Lodbrok, such as Ragnarssona þáttr, the Geatish king Herraud gives a small lindworm as a gift to his daughter Þóra Town-Hart after which it grows into a large serpent which encircles the girl’s bower and bites itself in the tail. The serpent is slain by Ragnar Lodbrok who marries Þóra. Ragnar later has a son with another woman named Kráka and this son is born with the image of a white snake in one eye. This snake encircled the iris and bit itself in the tail, and the son was named Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye.[19]

It is a common belief among indigenous people of the tropical lowlands of South America that waters at the edge of the world-disc are encircled by a snake, often an anaconda, biting its own tail.[20]

The ouroboros has certain features in common with the Biblical Leviathan. According to the Zohar, the Leviathan is a singular creature with no mate, «its tail is placed in its mouth», while Rashi on Baba Batra 74b describes it as «twisting around and encompassing the entire world». The identification appears to go back as far as the poems of Kalir in the 6th–7th centuries.[citation needed]

The Ouroboros as an auroral Phenomenon[edit]

Following an exhaustive survey, historical linguist Marinus van der Sluijs and plasma physicist Anthony Peratt suggested that the ouroboros has a specific origin in time, in the 5th or 4th millennium BCE,[21][22] and was ultimately based on globally independent observations of an intense aurora, with somewhat different characteristics than the familiar aurora.[23] Specifically, the ouroboros could have represented an auroral oval seen as a whole, at a time when it was smaller and located closer to the equator than now. That could have been the case during geomagnetic excursions, when the geomagnetic field weakens and the earth’s magnetic poles shift places.[24] Tok Thompson and Gregory Allen Schrempp cautiously allow that this new idea might «mark a bold new interdisciplinary venture made possible by modern science«.[25]

Connection to Indian thought[edit]

In the Aitareya Brahmana, a Vedic text of the early 1st millennium BCE, the nature of the Vedic rituals is compared to «a snake biting its own tail.»[26]

Ouroboros symbolism has been used to describe the Kundalini.[27] According to the medieval Yoga-kundalini Upanishad: «The divine power, Kundalini, shines like the stem of a young lotus; like a snake, coiled round upon herself she holds her tail in her mouth and lies resting half asleep as the base of the body» (1.82).[28]

Storl (2004) also refers to the ouroboros image in reference to the «cycle of samsara».[29]

Modern references[edit]

Jungian psychology[edit]

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung saw the ouroboros as an archetype and the basic mandala of alchemy. Jung also defined the relationship of the ouroboros to alchemy: Carl Jung, Collected Works, Vol. 14 para. 513.

The alchemists, who in their own way knew more about the nature of the individuation process than we moderns do, expressed this paradox through the symbol of the Ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail. The Ouroboros has been said to have a meaning of infinity or wholeness. In the age-old image of the Ouroboros lies the thought of devouring oneself and turning oneself into a circulatory process, for it was clear to the more astute alchemists that the prima materia of the art was man himself. The Ouroboros is a dramatic symbol for the integration and assimilation of the opposite, i.e. of the shadow. This ‘feedback’ process is at the same time a symbol of immortality since it is said of the Ouroboros that he slays himself and brings himself to life, fertilizes himself, and gives birth to himself. He symbolizes the One, who proceeds from the clash of opposites, and he, therefore, constitutes the secret of the prima materia which … unquestionably stems from man’s unconscious.

The Jungian psychologist Erich Neumann writes of it as a representation of the pre-ego «dawn state», depicting the undifferentiated infancy experience of both humankind and the individual child.[30]

Kekulé’s dream[edit]

The ouroboros, Kekulé’s inspiration for the structure of benzene

Kekulé’s proposal for the structure of benzene (1872)

The German organic chemist August Kekulé described the eureka moment when he realised the structure of benzene, after he saw a vision of Ouroboros:[31]

I was sitting, writing at my text-book; but the work did not progress; my thoughts were elsewhere. I turned my chair to the fire and dozed. Again the atoms were gamboling before my eyes. This time the smaller groups kept modestly in the background. My mental eye, rendered more acute by the repeated visions of the kind, could now distinguish larger structures of manifold conformation: long rows, sometimes more closely fitted together; all twining and twisting in snake-like motion. But look! What was that? One of the snakes had seized hold of its own tail, and the form whirled mockingly before my eyes. As if by a flash of lightning I awoke; and this time also I spent the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis.

Cosmos[edit]

Martin Rees used the ouroboros to illustrate the various scales of the universe, ranging from 10−20 cm (subatomic) at the tail, up to 1025 cm (supragalactic) at the head.[32] Rees stressed «the intimate links between the microworld and the cosmos, symbolised by the ouraborus«,[33] as tail and head meet to complete the circle.

Cybernetics[edit]

Cybernetics deployed circular logics of causal action in the core concept of feedback in the directive and purposeful behaviour in human and living organisms, groups, and self-regulating machines. The general principle of feedback describes a circuit (electronic, social, biological, or otherwise) in which the output or result is a signal that influences the input or causal agent through its response to the new situation. W. Ross Ashby applied ideas from biology to his own work as a psychiatrist in «Design for a Brain» (1952): that living things maintain essential variables of the body within critical limits with the brain as a regulator of the necessary feedback loops. Parmar contextualises his practices as an artist in applying the cybernetic Ouroboros principle to musical improvisation.[34]

Hence the snake eating its tail is an accepted image or metaphor in the autopoietic calculus for self-reference,[35] or self-indication, the logical processual notation for analysing and explaining self-producing autonomous systems and «the riddle of the living», developed by Francisco Varela. Reichel describes this as:

…an abstract concept of a system whose structure is maintained through the self-production of and through that structure. In the words of

Kauffman, is ‘the ancient mythological symbol of the worm ouroboros embedded in a mathematical, non-numerical calculus.[36][37]

The calculus derives from the confluence of the cybernetic logic of feedback, the sub-disciplines of autopoiesis developed by Varela and Humberto Maturana, and calculus of indications of George Spencer Brown. In another related biological application:

It is remarkable, that Rosen’s insight, that metabolism is just a mapping…, which may be too cursory for a biologist, turns out to show us the way to construct recursively, by a limiting process, solutions of the self-referential Ouroborus equation f(f) = f, for an unknown function f, a way that mathematicians had not imagined before Rosen.[38][39]

Second-order cybernetics, or the cybernetics of cybernetics, applies the principle of self-referentiality, or the participation of the observer in the observed, to explore observer involvement in all behaviour and the praxis of science[40] including D.J. Stewart’s domain of «observer valued imparities».[41]

Armadillo girdled lizard[edit]

The genus of the armadillo girdled lizard, Ouroborus cataphractus, takes its name from the animal’s defensive posture: curling into a ball and holding its own tail in its mouth.[42]

Pescadillas are often presented biting their tails.

In Iberian culture[edit]

A medium-sized European hake, known in Spanish as pescadilla and in Portuguese as pescada, is often presented with its mouth biting its tail. In Spanish it receives the name of pescadilla de rosca («torus hake»).[43]. Both expressions Uma pescadinha de rabo na boca «tail-in mouth little hake» and La pescadilla que se muerde la cola, «the hake that bites its tail», are proverbial Portuguese and Spanish expressions for circular reasoning and vicious circles.[44]

Dragon Gate Pro-Wrestling[edit]

The Kobe, Japan-based Dragon Gate Pro-Wrestling promotion used a stylised ouroboros as their logo for the first 20 years of the company’s existence. The logo is a silhouetted dragon twisted into the shape of an infinity symbol, devouring its own tail. In 2019, the promotion dropped the infinity dragon logo in favour of a shield logo.

In fiction[edit]

«Ouroboros» is an episode of the British science-fiction sitcom Red Dwarf,[45] in which one character is revealed to be his own father due to time travel. The concept also features in Claire North’s ‘the fifteen lives of Harry August.

The Worm Ouroboros is a high-fantasy novel written by E. R. Eddison. Much like the cyclical symbol of the ouroboros eating its own tail, the novel ends the way it begins.

The Ouroboros is used as a main plot device in Lisa Maxwell’s The Last Magician series.

The main six playable characters of the video game Xenoblade Chronicles 3 are able to transform into fiercely powerful forms called Ouroboros, which are ultimately tied to the fate of their world.[46]

The Ouroboros is the adopted symbol of the End Times-obsessed Millennium Group in the TV series Millennium. It also briefly appears when Dana Scully gets a tattoo of it in The X-Files episode «Never Again».

The Ouroboros is referenced in the science fiction short story All You Zombies by American writer Robert A. Heinlein as ‘the worm Ouroboros, the world snake’. The short story later serves as inspiration for the movie Predestination (2014).

In the A Discovery of Witches novels and television adaptation, the crest of the de Clermont family is an ouroboros. The symbol plays a significant role in the alchemical plot of the story.

In The Wheel of Time, the Aes Sedai wear a «Great Serpent» ring, described as a snake consuming its own tale. This image evokes the idea of eternity, and the cyclical nature of time and creation (major themes of the series, throughout).

Splatoon 3 has a similar creature called the Horrorboros which is based off the ouroboros.

See also[edit]

- Amphisbaena

- Cyclic model

- Dragon (M. C. Escher)

- Endless knot

- Ensō

- Eternal return (Eliade)

- Eternalism (philosophy of time)

- Historic recurrence

- Hoop snake

- Infinite loop

- Möbius strip

- Quine (computing)

- Self-reference

- Social cycle theory

- Strange loop

- Three hares

- Valknut

- The Worm Ouroboros

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Theodoros Pelecanos’s manuscript of an alchemical tract attributed to Synesius, in Codex Parisinus graecus 2327 in the Bibliothèque Nationale, France, mentioned s.v. ‘alchemy’, The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0199545561

- ^ «uroboros». Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019.

- ^ «Salvador Dalí: Alchimie des Philosophes | The Ouroboros». Academic Commons. Willamette University.

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1940), οὐροβόρος

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1940), οὐρά

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1940), βορά

- ^ Arien Mack (1999). Humans and Other Animals. Ohio State University Press. p. 359.

- ^ Mattison, Chris (2007). The New Encyclopedia of Snakes. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-691-13295-2.

- ^ Hornung, Erik. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Cornell University Press, 1999. pp. 38, 77–78

- ^ Hornung, Erik (1982). Conceptions of God in Egypt: The One and the Many. Cornell University Press. pp. 163–64.

- ^ Hornung 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Servius, note to Aeneid 5.85: «according to the Egyptians, before the invention of the alphabet the year was symbolized by a picture, a serpent biting its own tail because it recurs on itself» (annus secundum Aegyptios indicabatur ante inventas litteras picto dracone caudam suam mordente, quia in se recurrit), as cited by Danuta Shanzer, A Philosophical and Literary Commentary on Martianus Capella’s De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii Book 1 (University of California Press, 1986), p. 159.

- ^ van der Sluijs, Marinus Anthony; Peratt, Anthony L. (2009). «The Ourobóros as an Auroral Phenomenon». Journal of Folklore Research. 46 (1): 3–41. doi:10.2979/JFR.2009.46.1.3. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 40206938. S2CID 162226473.

- ^ Origen, Contra Celsum 6.25.

- ^ Hornung 2002, p. 76.

- ^ Eliade, Mircea (1976). Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashions. Chicago and London: U of Chicago Press. pp. 55, 93–113.

- ^ Bekhrad, Joobin. «The ancient symbol that spanned millennia». BBC. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Lambsprinck: De Lapide Philosophico. E Germanico versu Latine redditus, per Nicolaum Barnaudum Delphinatem …. Sumptibus LUCAE JENNISSI, Frankfurt 1625, p. 17.

- ^ Jurich, Marilyn (1998). Scheherazade’s Sisters: Trickster Heroines and Their Stories in World Literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29724-3.

- ^ Roe, Peter (1986), The Cosmic Zygote, Rutgers University Press

- ^ Daily, Charles (2022). The Serpent Symbol in Tradition. Google Books. pp. 218–219.

- ^ Daily, Charles (24 January 2022). The Serpent Symbol in Tradition. Books Google. ISBN 9781914208690.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Marinus Anthony van der Sluijs and Anthony L. Peratt (2009). «The Ouroboros as an Auroral Phenomenon». Folklore Research 46, No. 1: 17.

- ^ van der Sluijs, Marinus Anthony (2021). The Earth’s Aurora. Vancouver: All-Round Publications. pp. 99, 102, 216.

- ^ Tok Thompson, Gregory Allen Schrempp (2020). The Truth of Myth: World Mythologies in Theory and Everyday Life. UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 157–159. ISBN 9780190222789.

- ^ Witzel, M., «The Development of the Vedic Canon and its Schools: The Social and Political Milieu» in Witzel, Michael (ed.) (1997), Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts. New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas, Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora vol. 2, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 325 footnote 346

- ^ Henneberg, Maciej; Saniotis, Arthur (24 March 2016). The Dynamic Human. Bentham Science Publishers. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-68108-235-6.

- ^ Mahony, William K. (1 January 1998). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. SUNY Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-7914-3579-3.

- ^ «When Shakti is united with Shiva, she is a radiant, gentle goddess; but when she is separated from him, she turns into a terrible, destructive fury. She is the endless Ouroboros, the dragon biting its own tail, symbolizing the cycle of samsara.» Storl, Wolf-Dieter (2004). Shiva: The Wild God of Power and Ecstasy. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-59477-780-6.

- ^ Neumann, Erich. (1995). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Bollington series XLII: Princeton University Press. Originally published in German in 1949.

- ^ Read, John (1957). From Alchemy to Chemistry. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-486-28690-7.

- ^ M Rees Just Six Numbers (London 1999) p. 7-8

- ^ M Rees Just Six Numbers (London 1999) p. 161

- ^ Parmar, Robin. «No Input Software: Cybernetics, Improvisation, and the Machinic Phylum.» ISSTA 2011 (2014). He further discusses the cybernetics in elementary actions (like picking up a drum stick), the evolution of cybernetic science from Norbert Wiener to Gordon Pask, Heinz von Foerster, and Autopoiesis, and in related fields such as Autocatalysis, the philosophical system of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, and Manuel DeLanda.

- ^ Varela, Francisco J. «A Calculus for Self-reference.» International Journal of General Systems 2 (1975): 5–24.

- ^ Kauffman sub-reference: Kauffman LH. 2002. Laws of form and form dynamics. Cybernetics & Human Knowing 9(2): 49–63, pp57–58.

- ^ Reichel, André (2011). «Snakes all the Way Down: Varela’s Calculus for Self-Reference and the Praxis of Paradis» (PDF). Systems Research and Behavioral Science. 28 (6): 646–662. doi:10.1002/sres.1105. S2CID 16051196.

- ^ Gutiérrez, Claudio, Sebastián Jaramillo, and Jorge Soto-Andrade. «Some Thoughts on A.H. Louie’s More Than Life Itself: A Reflection on Formal Systems and Biology.» Axiomathes 21, no. 3 (2011): 439–454, p448.

- ^ Soto-Andrade, Jorge, Sebastia Jaramillo, Claudio Gutierrez, and Juan-Carlos Letelier. «Ouroboros Avatars: A Mathematical Exploration of Self-reference and Metabolic Closure.» «One of the most important characteristics observed in metabolic networks is that they produce themselves. This intuition, already advanced by the theories of Autopoiesis and (M,R)-systems, can be mathematically framed in a weird-looking equation, full of implications and potentialities: f(f) = f. This equation (here referred to as Ouroboros equation), arises in apparently dissimilar contexts, like Robert Rosen’s synthetic view of metabolism, hyper set theory and, importantly, untyped lambda calculus. …We envision that the ideas behind this equation, a unique kind of mathematical concept, initially found in biology, would play an important role in the development of a true systemic theoretical biology. MIT Press online.

- ^ Müller, K H. Second-order Science: The Revolution of Scientific Structures. Complexity, design, society. Edition Echoraum, 2016.

- ^ Scott, Bernard. «The Cybernetics of Systems of Belief.» Kybernetes: The International Journal of Systems & Cybernetics 29, no. 7-8 (2000): 995–998.

- ^ Stanley, Edward L.; Bauer, Aaron M.; Jackman, Todd R.; Branch, William R.; Mouton, P. Le Fras N. (2011). «Between a rock and a hard polytomy: Rapid radiation in the rupicolous girdled lizards (Squamata: Cordylidae)». Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 58 (1): 53–70. (Ouroborus cataphractus, new combination).

- ^ Spínola Bruzón, Carlos. «Pescadilla; entre pijota y pescada.- Grupo Gastronómico Gaditano». grupogastronomicogaditano.com (in European Spanish). Grupo Gastronómico Gaditano. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

La pescadilla se fríe en forma de rosca, de modo que la cola esté cogida por los dientes del pez.

- ^ «pescadilla». Diccionario de la lengua española (in Spanish) (24th ed.). RAE-ASALE. 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ «Ouroboros». Red Dwarf: The Official Site. Grant Naylor Productions. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ «Xenoblade Chronicles 3 Direct – Nintendo Switch». Nintendo of America. 22 June 2022 – via YouTube.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bayley, Harold S (1909). New Light on the Renaissance. Kessinger. Reference pages hosted by the University of Pennsylvania

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Hornung, Erik (2002). The Secret Lore of Egypt: Its Impact on the West. Cornell University Press.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press – via perseus.tufts.edu.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ouroboros.

- BBC Culture – The ancient symbol that spanned millennia

- Текст

- Веб-страница

уроборос

0/5000

Результаты (латинский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

Ouroboros

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Другие языки

- English

- Français

- Deutsch

- 中文(简体)

- 中文(繁体)

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Español

- Português

- Русский

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Ελληνικά

- العربية

- Polski

- Català

- ภาษาไทย

- Svenska

- Dansk

- Suomi

- Indonesia

- Tiếng Việt

- Melayu

- Norsk

- Čeština

- فارسی

Поддержка инструмент перевода: Клингонский (pIqaD), Определить язык, азербайджанский, албанский, амхарский, английский, арабский, армянский, африкаанс, баскский, белорусский, бенгальский, бирманский, болгарский, боснийский, валлийский, венгерский, вьетнамский, гавайский, галисийский, греческий, грузинский, гуджарати, датский, зулу, иврит, игбо, идиш, индонезийский, ирландский, исландский, испанский, итальянский, йоруба, казахский, каннада, каталанский, киргизский, китайский, китайский традиционный, корейский, корсиканский, креольский (Гаити), курманджи, кхмерский, кхоса, лаосский, латинский, латышский, литовский, люксембургский, македонский, малагасийский, малайский, малаялам, мальтийский, маори, маратхи, монгольский, немецкий, непальский, нидерландский, норвежский, ория, панджаби, персидский, польский, португальский, пушту, руанда, румынский, русский, самоанский, себуанский, сербский, сесото, сингальский, синдхи, словацкий, словенский, сомалийский, суахили, суданский, таджикский, тайский, тамильский, татарский, телугу, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, уйгурский, украинский, урду, филиппинский, финский, французский, фризский, хауса, хинди, хмонг, хорватский, чева, чешский, шведский, шона, шотландский (гэльский), эсперанто, эстонский, яванский, японский, Язык перевода.

- Lässt dies ihn übermütig werden?

- памятник

- восхищаться

- Это виртуальный мир. Здесь много поддело

- бежать

- Я пишу письма

- shooting accuracy

- Also, I assume this pano tool is made on

- На прошлой неделе я встретил своего друг

- Лягушки ловят мошку

- возьми с собой чай

- об качествах, которыми я восхищаюсь

- Scot was awesome program…too bad that SO

- Лягушки ловят мошку

- они добрые и всегда обо мне заботятся

- Нелогичный ответ; неосуществимая задача;

- Ради народних депутатів

- дом мэри

- The Council of people’s deputies

- брайн находиться на кухне

- Lässt ob dies ihn übermütig werden?

- про что поговорим?

- у меня нет брата

- Then I’m your onii-chan

Эта статья — о символе. Другие значения термина «уроборос» см. на странице Уроборос (значения).

Изображение уробороса в алхимическом трактате 1478 г. Автор — Феодор Пелеканос (греч. Θεόδωρος Πελεκάνος)

Уробо́рос (др.-греч. οὐροβόρος от οὐρά «хвост» + βορά «пища, еда») — свернувшийся в кольцо змей или ящерица, кусающий себя за хвост. Является одним из древнейших символов[1][2][3], известных человечеству, точное происхождение которого — исторический период и конкретную культуру — установить невозможно[4].

Этот символ имеет множество различных значений. Наиболее распространённая трактовка описывает его как репрезентацию вечности и бесконечности, в особенности — циклической природы жизни: чередования созидания и разрушения, жизни и смерти, постоянного перерождения и гибели. Символ уробороса имеет богатую историю использования в религии, магии, алхимии, мифологии и психологии[3]. Одним из его аналогов является свастика — оба этих древних символа означают движение космоса[5].

Считается, что в западную культуру данный символ пришёл из Древнего Египта, где первые изображения свернувшейся в кольцо змеи датированы периодом между 1600 и 1100 годами до н. э.; они олицетворяли вечность и вселенную, а также цикл смерти и перерождения[6]. Ряд историков полагает, что именно из Египта символ уробороса перекочевал в Древнюю Грецию, где стал использоваться для обозначения процессов, не имеющих начала и конца[7]. Однако точно установить происхождение этого образа затруднительно, поскольку его близкие аналоги также встречаются в культурах Скандинавии, Индии, Китая и Греции[6].

Символ свернувшейся в кольцо змеи встречается в неявной форме в Мезоамерике, в частности, у ацтеков. При том, что змеи играли значительную роль в их мифологии[8], вопрос прямой связи пантеона ацтекских богов с уроборосом среди историков остаётся открытым — так, без каких-либо развёрнутых комментариев Б. Розен называет Кетцалькоатля[9], а М. Лопес — Коатликуэ[10].

Интерес к уроборосу сохранялся на протяжении многих веков — в частности, заметную роль он играет в учении гностиков[11], а также является важным элементом (в метафорическом смысле) ремесла средневековых алхимиков, символизируя преображение элементов в философский камень, требующийся для трансмутации металлов в золото[12], а также олицетворяя хаос в мифологическом понимании термина[13].

В новейшее время швейцарским психоаналитиком К. Г. Юнгом был вложен новый смысл в символ уробороса. Так в ортодоксальной аналитической психологии архетип уробороса символизирует темноту и саморазрушение одновременно с плодородностью и творческой потенцией. Дальнейшие исследования данного архетипа нашли наибольшее отражение в работах юнгианского психоаналитика Эриха Нойманна, обозначившего уроборос в качестве ранней стадии развития личности[14].

Древний Египет, Израиль и Греция

![Изображение уробороса из книги «Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra» (эллинистический период)[1]](https://wiki2.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/Chrysopoea_of_Cleopatra_1.png/im194-Chrysopoea_of_Cleopatra_1.png)

Изображение уробороса из книги «Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra» (эллинистический период)[1]

Д. Бопри, описывая появление изображений уробороса в Древнем Египте, утверждает, что этот символ наносился на стены гробниц и обозначал стражника загробного мира, а также пороговый момент между смертью и перерождением[15]. Первое появление знака уробороса в Древнем Египте датируется примерно 1600 годом до н. э. (по другим данным — 1100 годом[16])[17]. Свернувшаяся в кольцо змея, например, высечена на стенах храма Осириса в древнем городе Абидосе[18]. Символ, помимо прочего, являлся репрезентацией продолжительности, вечности и/или бесконечности[19]. В понимании египтян уроборос был олицетворением вселенной, рая, воды, земли и звёзд — всех существующих элементов, старых и новых[20]. Сохранилась поэма, написанная фараоном Пианхи, в которой упоминается уроборос[21].

У. Беккер, говоря о символизме змей как таковых, отмечает, что евреи издревле рассматривали их в качестве угрожающих, злых существ. В тексте Ветхого Завета, в частности, змей причисляется к «нечистым» созданиям; он символизирует Сатану и зло в целом — так, Змей является причиной изгнания из рая Адама и Евы[22]; взгляда, согласно которому между Змеем из райского сада и уроборосом ставился знак равенства, также придерживались некоторые гностические секты, к примеру, Офиты[23].

Историки полагают, что из Египта символ уробороса попал в Древнюю Грецию, где наравне с Фениксом стал олицетворять процессы, не имеющие конца и начала[7]. В Греции змеи были предметом почитания, символом здоровья, а также связывались с загробным миром, что нашло отражение во множестве мифов и легенд. Само слово «дракон» (др.-греч. δράκων) переводится дословно как «змея»[24].

Древний Китай

Р. Робертсон и А. Комбс отмечают, что в Древнем Китае уроборос назывался «Zhulong» и изображался в виде создания, совмещающего в себе свинью и дракона, кусающего себя за хвост. Многие учёные придерживаются взгляда, что со временем данный символ претерпел значительные изменения и трансформировался в традиционного «китайского дракона», символизирующего удачу[6]. Одни из первых упоминаний об уроборосе как символе датированы 4200 годом до н. э.. Первые находки фигурок свернувшихся в кольцо драконов относят к культуре Хуншань (4700—2900 до н. э.). Одна из них, в форме полного круга, находилась на груди покойника[25].

Также существует мнение, согласно которому с символом уробороса в древнекитайской натурфилософии напрямую связана монада, изображающая концепцию «инь и ян»[17]. Также для изображений уробороса в Древнем Китае характерно размещение яйца внутри пространства, которое охватывает телом змея; предполагается, что это является одноимённым символом, созданным самим Творцом[26]. «Центр» уробороса — упомянутое пространство внутри кольца — в философии нашёл отражение в понятии «дао», что означает «путь человека»[27].

Древняя Индия

Основная статья: Шеша

В ведийской религии и индуизме в качестве одной из форм бога фигурирует Шеша (или Ананта-шеша). Изображения и описания Шеши в виде змеи, кусающей себя за хвост, комментирует Д. Торн-Бёрд, указывая на его связь с символом уробороса[17]. С древних времён и по сей день в Индии почитались змеи (наги) — покровители водных путей, озёр и источников, а также воплощения жизни и плодородия. Кроме того, наги олицетворяют непреходящий цикл времени и бессмертие. Согласно легендам, все наги являются отпрысками трёх змеиных богов — Васуки, Такшаки (англ.) (рус. и Шеши[28].

Изображение Шеши можно часто увидеть на картинах, изображающих свернувшуюся в клубок змею, на которой, скрестив ноги, восседает Вишну. Витки тела Шеши символизируют нескончаемый кругооборот времени[29]. В более широкой трактовке мифа огромных размеров змея (наподобие кобры) обитает в мировом океане и имеет сотню голов. Пространство же, скрываемое массивным телом Шеши, включает в себя все планеты Вселенной[30]; если быть точным, именно Шеша и держит эти планеты своими многочисленными головами, а также распевает хвалебные песни в честь Вишну[31]. Образ Шеши, помимо прочего, также использовался как защитный тотем индийскими махараджами, поскольку существовало поверье, будто змей, опоясавший своим телом землю, охраняет её от злых сил[32]. Само слово «Шеша» обозначает «остаток», что отсылает к остающемуся после того, как всё созданное вернётся обратно в первичную материю[33]. По мнению Клауса Клостермайера, философское толкование образа Шеши даёт возможность понять историю с точки зрения философии индуизма, согласно которой история не ограничивается человеческой историей на планете Земля или историей одной отдельно взятой вселенной: существует бесчисленное множество вселенных, в каждой из которых постоянно разворачиваются какие-то события[34].

Германо-скандинавская мифология

В германо-скандинавской мифологии, как пишет Л. Фубистер[35], форму уробороса принимает Ёрмунганд (также называемый «Мидгардским змеем» или «Мидгардсормом», богом зла) — самец[36][37] огромного змееподобного дракона, один из детей бога Локи и великанши Ангрбоды. Когда отец и предводитель асов Один узнал от норн, что Ёрмунганд убьёт Тора — он сослал его на дно морское. В океане Ёрмунганд разросся до столь больших размеров, что смог опоясать своим телом землю и укусить себя за хвост — именно здесь, в мировом океане, он будет находиться бо́льшую часть времени вплоть до наступления Рагнарёка, когда ему будет суждено в последней битве встретиться с Тором[38].

Скандинавские легенды содержат описание двух встреч змея и Тора до Рагнарёка. Первая встреча произошла, когда Тор отправился к королю гигантов, Утгарда-Локи, чтобы выдержать три испытания физической силы. Первым из заданий было поднять королевского кота. Хитрость Утгарда-Локи заключалась в том, что на самом деле то был Ёрмунганд, превращённый в кошку; это сильно осложняло выполнение задания — единственным, чего смог достичь Тор, было заставить животное оторвать одну лапу от пола. Король гигантов, впрочем, признал это успешным выполнением поставленной задачи и раскрыл обман. Данная легенда содержится в тексте «Младшей Эдды»[36].

Второй раз Ёрмунганд и Тор встретились, когда последний вместе с Гимиром отправились на рыбалку. В качестве наживки использовалась бычья голова; когда лодка Тора проплывала над змеем, тот отпустил хвост и вцепился в наживку. Борьба продолжалась достаточно долго. Тору удалось вытащить голову чудовища на поверхность — он хотел поразить его ударом Мьёльнира, однако Гимир не выдержал вида корчащегося в агонии змея и перерезал леску, дав Ёрмунганду скрыться в пучине океана[36].

В ходе последней битвы (Рагнарёка), гибели Богов, Тор и Ёрмунганд встретятся в последний раз. Выбравшись из мирового океана, змей отравит своим ядом небо и землю, заставив водные просторы ринуться на сушу. Сразившись с Ёрмунгандом, Тор отобьёт голову чудовищу, однако сам сможет отойти только на девять шагов — брызжущий из тела чудовища яд поразит его насмерть[9].

Гностицизм и алхимия

Уроборос. Гравюра Л. Дженниса из книги алхимических эмблем «Философский камень». 1625. Символическое «принесение в жертву», то есть укус за хвост змеи, означает приобщение к вечности в конце Великого делания

В учении христианских гностиков уроборос был отображением конечности материального мира. Один из ранних гностических трактатов «Pistis Sophia» давал следующее определение: «материальная тьма есть великий дракон, что держит хвост во рту, за пределами всего мира и окружая весь мир»[6]; согласно этому же сочинению, тело мистической змеи имеет двенадцать частей (символически связывающихся с двенадцатью месяцами). В гностицизме уроборос олицетворяет одновременно и свет (др.-греч. ἀγαθοδαίμων — дух добра), и тьму (κακοδαίμων — дух зла). Тексты, обнаруженные в Наг-Хаммади, содержат ряд отсылок к уроборостической природе создания и распада всего мироздания, которые напрямую связаны с великим змием[39]. Образ свернувшегося в кольцо змея играл заметную роль в гностическом учении — к примеру, в его честь были названы несколько сект[11].

Средневековые алхимики использовали символ уробороса для обозначения множества «истин»; так, на различных ксилографиях XVIII века змей, кусающий свой хвост, изображался практически на каждом из этапов алхимического действа. Частым было также изображение уробороса совместно с философским яйцом (англ.) (рус. (одним из важнейших элементов для получения философского камня)[6]. Алхимики считали уробороса отображением циклического процесса, в котором нагревание, испарение, охлаждение и конденсация жидкости способствуют процессу очищения элементов и преобразования их в философский камень или в золото[12].

Для алхимиков уроборос был воплощением цикла смерти и перерождения, одной из ключевых идей дисциплины; змей, кусающий себя за хвост, олицетворял законченность процесса трансформации, преобразования четырёх элементов[40]. Таким образом, уроборос являл «opus circulare» (или «opus circularium») — течение жизни, то, что буддисты называют «Бхавачакра», колесо бытия[41]. В данном смысле символизируемое уроборосом было наделено крайне позитивным смыслом, оно являлось воплощением цельности, полного жизненного цикла[18]. Свернувшийся в кольцо змей очерчивал хаос и сдерживал его, поэтому воспринимался в виде «prima materia»; уроборос часто изображался двухголовым и/или имеющим сдвоенное тело, таким образом олицетворяя единство духовности и бренности бытия[13].

Новейшее время

Знаменитый английский алхимик и эссеист сэр Томас Браун (1605—1682) в своём трактате «Письмо другу», перечисляя тех, кто умер в день рождения, изумлялся тому, что первый день жизни столь часто совпадает с последним и что «хвост змеи возвращается к ней в пасть ровно в то же время». Он также считал уробороса символом единства всех вещей[42]. Немецкий химик Фридрих Август Кекуле (1829—1896) утверждал, что приснившееся ему кольцо в форме уробороса натолкнуло его на открытие циклической формулы бензола[43].

Печать Теософского общества, основанного Еленой Блаватской, имеет форму увенчанного омом уробороса, внутри которого расположены другие символы: шестиконечная звезда, анх и свастика[44]. Изображение уробороса используется масонскими великими ложами в качестве одного из главных отличительных символов. Основной идеей, вкладываемой в использование этого символа, является вечность и непрерывность существования организации. Уроборос можно увидеть на гербовой печати Великого востока Франции и Объединённой великой ложи России[45].

Уроборос также изображался на гербах, например, рода Доливо-Добровольские, венгерского города Хайдубёсёрмень и самопровозглашённой Республики Фиуме. Изображение свернувшейся в кольцо змеи можно встретить на современных картах Таро; используемая для гаданий карта с изображением уробороса означает бесконечность[46].

Образ уробороса активно используется в художественных фильмах и литературе: например, в «Бесконечной истории» Петерсена[47], «Красном карлике» Гранта и Нейлора[48], «Священная книга оборотня» Пелевина, «Стальном алхимике» Аракавы[49], «Колесе Времени» Джордана[36], в сериалах «Хелмок гроув», «12 обезьян» и «Секретных материалах» (серия «Never Again» (англ.) (рус.) Картера. Мотив закольцованной змеи часто встречается в татуировках, найдя отображение в виде рисунков, имитирующих различные узлы и в целом относящихся к кельтскому искусству[50]. Помимо прочего, символ уробороса используется в архитектуре для декорирования полов и фасадов зданий[4].

Американский физик и биолог Р. Фокс в книге «Энергия и эволюция жизни на Земле»[51] использует образ уробороса для иллюстрации одной из фундаментальных проблем теории зарождения жизни: для синтеза белков нужны нуклеиновые кислоты, а для их синтеза — белки (по современным представлениям проблема решается с помощью гипотезы «мира РНК»).

Паисий Святогорец говорил о последних временах: «Написано, что когда распространится эмблема со змеёй, пожирающей собственный хвост, это будет значить, что евреи поработили весь мир. Сейчас этот знак поставили на некоторые денежные купюры. Число 666 распространяется уже и в Китае, и в Индии».[52]

Британский писатель Эрик Рюкер Эддисон считается одним из основателей литературного жанра фэнтези. И главным его произведением был фэнтезийный роман «Змей Уроборос[en]» (1922).

Характерной чертой основного текста экспериментального романа «Поминки по Финнегану» (1923—1939) ирландского писателя Джеймса Джойса является мотив бесконечного возвращения (структура Уробороса).

Аналитическая психология

В теории архетипов, согласно мнению Карла Густава Юнга, уроборос является символом, предполагающим темноту и саморазрушение одновременно с плодородностью и творческой потенцией. Этот знак отображает этап, существующий между описанием и разделением противоположностей (принцип, согласно которому дуализм является неискоренимым и незаменимым условием всей психической жизни)[14]. Данная идея в дальнейшем была развита учеником Юнга Эрихом Нойманном, выдвинувшим предположение, что уроборос, понимаемый как метафора, является ранней стадией развития личности. Закольцованная форма зме́я, таким образом, показывает недифференцированность инстинктов жизни и смерти, равно как любви и агрессии, а также фрагментированную самость (то есть отсутствие различий между субъектом и объектом). По Нойманну, эта стадия развития, получившая название «уроборической», являет фантазии чистоты и партеногенеза у младенца[14].

В более поздних исследованиях юнгианцев архетип уробороса уже понимается шире — в качестве единого целого, объединяющего сознание и бессознательное, и содержащего в себе как маскулинную, так и феминную сущности. В ходе же прохождения индивидуумом уроборической стадии развития (по Нойманну) составляющее уробороса разделяется на непосредственно Эго и Мировых родителей (архетип, являющийся фундаментом для ожиданий и чувств человека по отношению к родителям[53]). Поскольку архетип Мировых родителей на данном этапе становится в позицию конфронтации с Эго, их взаимодействие является первым этапом становления бессознательной самости человека, Героя[54].

Примечания

- ↑ 1 2 Kleisberg, Glenn. Lost Knowledge of the Ancients: A Graham Hancock Reader. — Inner Traditions / Bear & Co, 2010. — P. 27. — ISBN 9781591431176.

- ↑ Ellis, Jeanette. Forbidden Rites: Your Complete Introduction to Traditional Witchcraft. — O Books, 2009. — P. 480. — ISBN 9781846941382.

- ↑ 1 2 Eire, Carlos. A very brief history of eternity. — Princeton University Press, 2010. — P. 29. — ISBN 9780691133577.

- ↑ 1 2 Gauding, Madonna. The Signs and Symbols Bible: The Definitive Guide to Mysterious Markings. — Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2009. — P. 89. — ISBN 9781402770043.

- ↑ Murphy, Derek. Jesus Didn’t Exist! the Bible Tells Me So. — Lulu.com, 2006. — P. 61. — ISBN 9781411658783.