This article is about the male prostate gland. For the equivalent female prostate gland, see Skene’s gland. For the journal, see The Prostate.

| Prostate | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Details | |

| Precursor | Endodermic evaginations of the urethra |

| Artery | Internal pudendal artery, inferior vesical artery, and middle rectal artery |

| Vein | Prostatic venous plexus, pudendal plexus, vesical plexus, internal iliac vein |

| Nerve | Inferior hypogastric plexus |

| Lymph | internal iliac lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Prostata |

| MeSH | D011467 |

| TA98 | A09.3.08.001 |

| TA2 | 3637 |

| FMA | 9600 |

| Anatomical terminology

[edit on Wikidata] |

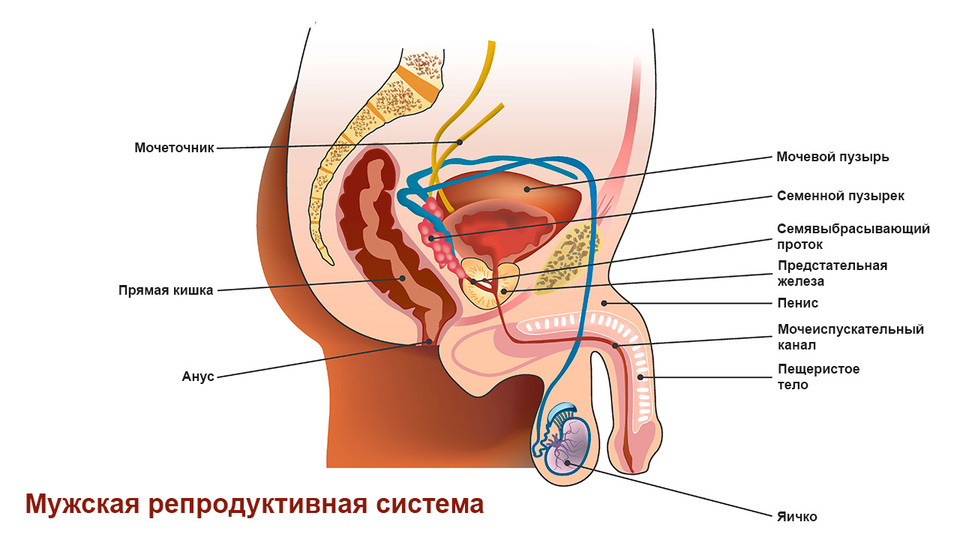

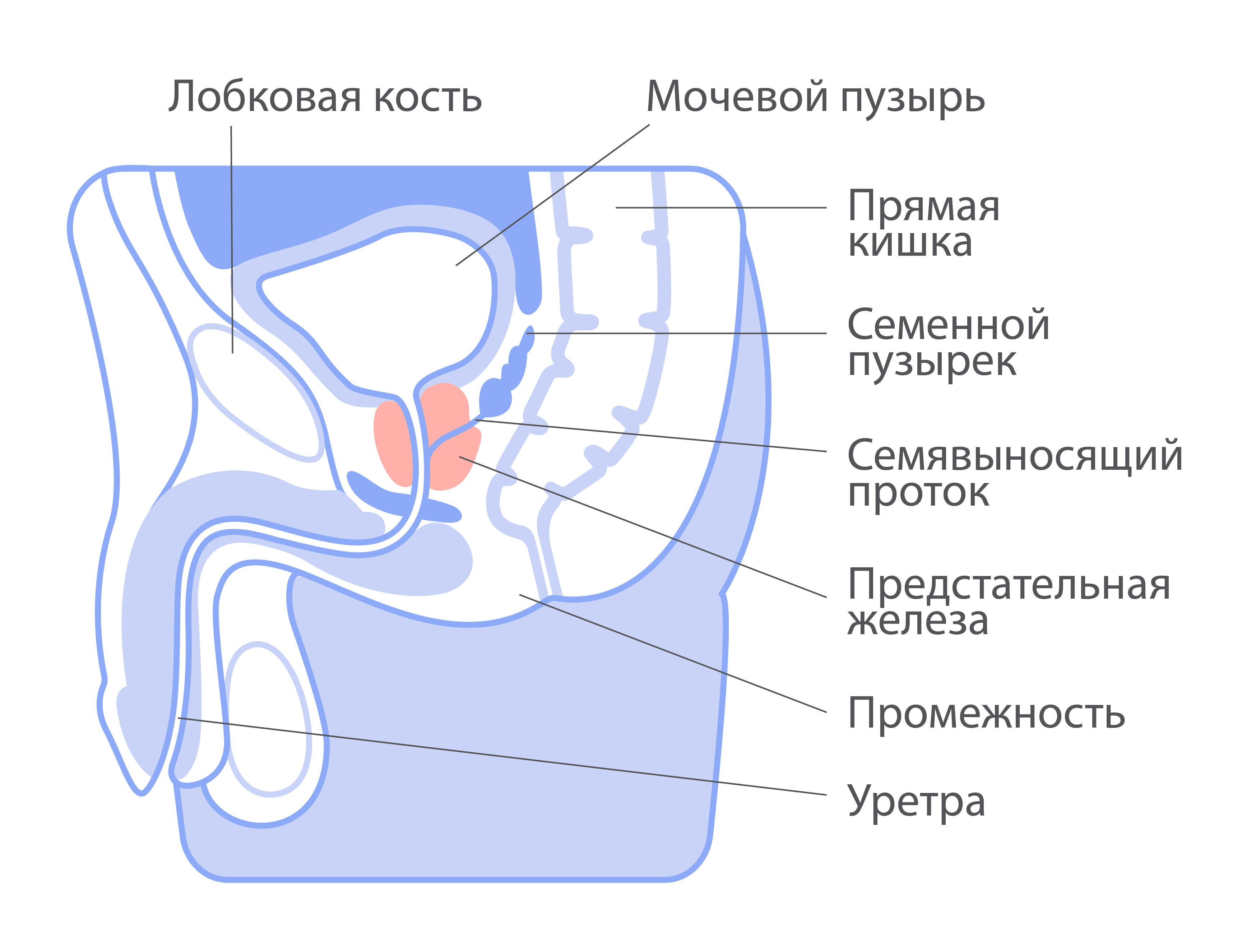

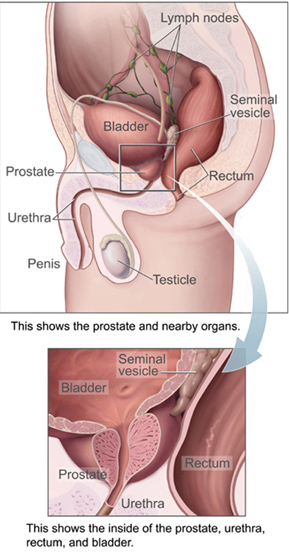

The prostate is both an accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found in all male mammals.[1] It differs between species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically. Anatomically, the prostate is found below the bladder, with the urethra passing through it. It is described in gross anatomy as consisting of lobes and in microanatomy by zone. It is surrounded by an elastic, fibromuscular capsule and contains glandular tissue as well as connective tissue.

The prostate glands produce and contain fluid that forms part of semen, the substance emitted during ejaculation as part of the male sexual response. This prostatic fluid is slightly alkaline, milky or white in appearance. The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm. The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first part of ejaculate, together with most of the sperm, because of the action of smooth muscle tissue within the prostate. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid, those in prostatic fluid have better motility, longer survival, and better protection of genetic material.

Disorders of the prostate include enlargement, inflammation, infection, and cancer. The word prostate comes from Ancient Greek προστάτης, prostátēs, meaning «one who stands before», «protector», «guardian», with the term originally used to describe the seminal vesicles.

Structure[edit]

The prostate is a gland of the male reproductive system. In adults, it is about the size of a walnut,[2] and has an average weight of about 11 grams, usually ranging between 7 and 16 grams.[3] The prostate is located in the pelvis. It sits below the urinary bladder and surrounds the urethra. The part of the urethra passing through it is called the prostatic urethra, which joins with the two ejaculatory ducts.[2] The prostate is covered in a surface called the prostatic capsule or prostatic fascia.[4]

The internal structure of the prostate has been described using both lobes and zones.[5][2] Because of the variation in descriptions and definitions of lobes, the zone classification is used more predominantly.[2]

The prostate has been described as consisting of three or four zones.[2][4] Zones are more typically able to be seen on histology, or in medical imaging, such as ultrasound or MRI.[2][5] The zones are:

| Name | Fraction of adult gland[2] | Description |

| Peripheral zone (PZ) | 70% | The back of the gland that surrounds the distal urethra and lies beneath the capsule. About 70–80% of prostatic cancers originate from this zone of the gland.[6][7] |

| Central zone (CZ) | 20% | This zone surrounds the ejaculatory ducts.[2] The central zone accounts for roughly 2.5% of prostate cancers; these cancers tend to be more aggressive and more likely to invade the seminal vesicles.[8] |

| Transition zone (TZ) | 5% | The transition zone surrounds the proximal urethra.[2] ~10–20% of prostate cancers originate in this zone. It is the region of the prostate gland that grows throughout life and causes the disease of benign prostatic enlargement.[6][7] |

| Anterior fibro-muscular zone (or stroma) | N/A | This area, not always considered a zone,[4] is usually devoid of glandular components and composed only, as its name suggests, of muscle and fibrous tissue.[2] |

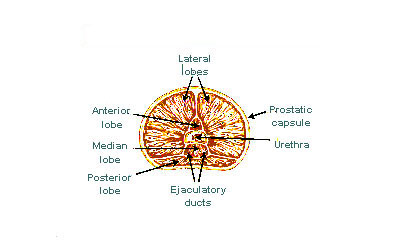

The «lobe» classification describes lobes that, while originally defined in the fetus, are also visible in gross anatomy, including dissection and when viewed endoscopically.[5][4] The five lobes are the anterior lobe or isthmus, the posterior lobe, the right and left lateral lobes, and the middle or median lobe.

-

Lobes of prostate

-

Zones of prostate

Inside of the prostate, adjacent and parallel to the prostatic urethra, there are two longitudinal muscle systems. On the front side (ventrally) runs the urethral dilator (musculus dilatator urethrae), on the backside (dorsally) runs the muscle switching the urethra into the ejaculatory state (musculus ejaculatorius).[9]

Blood and lymphatic vessels[edit]

The prostate receives blood through the inferior vesical artery, internal pudendal artery, and middle rectal arteries. These vessels enter the prostate on its outer posterior surface where it meets the bladder, and travel forward to the apex of the prostate.[4] Both the inferior vesical and the middle rectal arteries often arise together directly from the internal iliac arteries. On entering the bladder, the inferior vesical artery splits into a urethral branch, supplying the urethral prostate; and a capsular branch, which travels around the capsule and has smaller branches which perforate into the prostate.[4]

The veins of the prostate form a network – the prostatic venous plexus, primarily around its front and outer surface.[4] This network also receives blood from the deep dorsal vein of the penis, and is connected via branches to the vesical plexus and internal pudendal veins.[4] Veins drain into the vesical and then internal iliac veins.[4]

The lymphatic drainage of the prostate depends on the positioning of the area. Vessels surrounding the vas deferens, some of the vessels in the seminal vesicle, and a vessel from the posterior surface of the prostate drain into the external iliac lymph nodes.[4] Some of the seminal vesicle vessels, prostatic vessels, and vessels from the anterior prostate drain into internal iliac lymph nodes.[4] Vessels of the prostate itself also drain into the obturator and sacral lymph nodes.[4]

Microanatomy[edit]

The prostate consists of glandular and connective tissue.[2] Tall column-shaped cells form the lining (the epithelium) of the glands.[2] These form one layer or may be pseudostratified.[4] The epithelium is highly variable and areas of low cuboidal or flat cells can also be present, with transitional epithelium in the outer regions of the longer ducts.[10] The glands are formed as many follicles, which in drain into canals and subsequently 12–20 main ducts, These in turn drain into the urethra as it passes through the prostate.[4] There are also a small amount of flat cells, which sit next to the basement membranes of glands, and act as stem cells.[2]

The connective tissue of the prostate is made up of fibrous tissue and smooth muscle.[2] The fibrous tissue separates the gland into lobules.[2] It also sits between the glands and is composed of randomly orientated smooth-muscle bundles that are continuous with the bladder.[11]

Over time, thickened secretions called corpora amylacea accumulate in the gland.[2]

-

Microscopic glands of the prostate

Gene and protein expression[edit]

About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and almost 75% of these genes are expressed in the normal prostate.[12][13] About 150 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the prostate, with about 20 genes being highly prostate specific.[14] The corresponding specific proteins are expressed in the glandular and secretory cells of the prostatic gland and have functions that are important for the characteristics of semen, including prostate-specific proteins, such as the prostate specific antigen (PSA), and the Prostatic acid phosphatase.[15]

Development[edit]

In the developing embryo, at the hind end lies an inpouching called the cloaca. This, over the fourth to the seventh week, divides into a urogenital sinus and the beginnings of the anal canal, with a wall forming between these two inpouchings called the urorectal septum.[16] The urogenital sinus divides into three parts, with the middle part forming the urethra; the upper part is largest and becomes the urinary bladder, and the lower part then changes depending on the biological sex of the embryo.[16]

The prostatic part of the urethra develops from the middle, pelvic, part of the urogenital sinus, which is of endodermal origin.[17] Around the end of the third month of embryonic life, outgrowths arise from the prostatic part of the urethra and grow into the surrounding mesenchyme.[17] The cells lining this part of the urethra differentiate into the glandular epithelium of the prostate.[17] The associated mesenchyme differentiates into the dense connective tissue and the smooth muscle of the prostate.[18]

Condensation of mesenchyme, urethra, and Wolffian ducts gives rise to the adult prostate gland, a composite organ made up of several tightly fused glandular and non-glandular components. To function properly, the prostate needs male hormones (androgens), which are responsible for male sex characteristics. The main male hormone is testosterone, which is produced mainly by the testicles. It is dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a metabolite of testosterone, that predominantly regulates the prostate. The prostate gland enlarges over time, until the fourth decade of life.[4]

Function[edit]

The prostate secretes fluid which becomes part of semen. Semen is the fluid emitted (ejaculated) by males during the sexual response.[19] When sperm is emitted, it is transmitted from the vas deferens into the male urethra via the ejaculatory ducts, which lie within the prostate gland.[19] Ejaculation is the expulsion of semen from the urethra.[19] Semen is moved into the urethra following contractions of the smooth muscle of the vas deferens and seminal vesicles, following stimulation, primarily of the glans penis. Stimulation sends nerve signals via the internal pudendal nerves to the upper lumbar spine; the nerve signals causing contraction act via the hypogastric nerves.[19] After traveling into the urethra, the seminal fluid is ejaculated by contraction of the bulbocavernosus muscle.[19] The secretions of the prostate include proteolytic enzymes, prostatic acid phosphatase, fibrinolysin, zinc, and prostate-specific antigen.[4] Together with the secretions from the seminal vesicles, these form the major fluid part of semen.[4]

It is possible for some men to achieve orgasm solely through stimulation of the prostate gland, such as via prostate massage or anal intercourse.[20][21] This has led to the area of the rectal wall adjacent to the prostate to be popularly referred by the anatomically incorrect term, the «male G-spot».[22]

The prostate’s changes of shape, which facilitate the mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation, are mainly driven by the two longitudinal muscle systems running along the prostatic urethra. These are the urethral dilator (musculus dilatator urethrae) on the urethra’s front side, which contracts during urination and thereby shortens and tilts the prostate in its vertical dimension thus widening the prostatic section of the urethral tube,[23][24] and the muscle switching the urethra into the ejaculatory state (musculus ejaculatorius) on its backside.[9]

In case of an operation, e.g. because of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), damaging or sparing of these two muscle systems varies considerably depending on the choice of operation type and details of the procedure of the chosen technique. The effects on postoperational urination and ejaculation vary correspondingly.[25] (See also: Surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia).

Clinical significance[edit]

Inflammation[edit]

Micrograph showing an inflamed prostate gland, found in prostatitis. A large amount of darker cells, representing leukocytes, can be seen. An area without inflammation is seen on the left of the image. H&E stain.

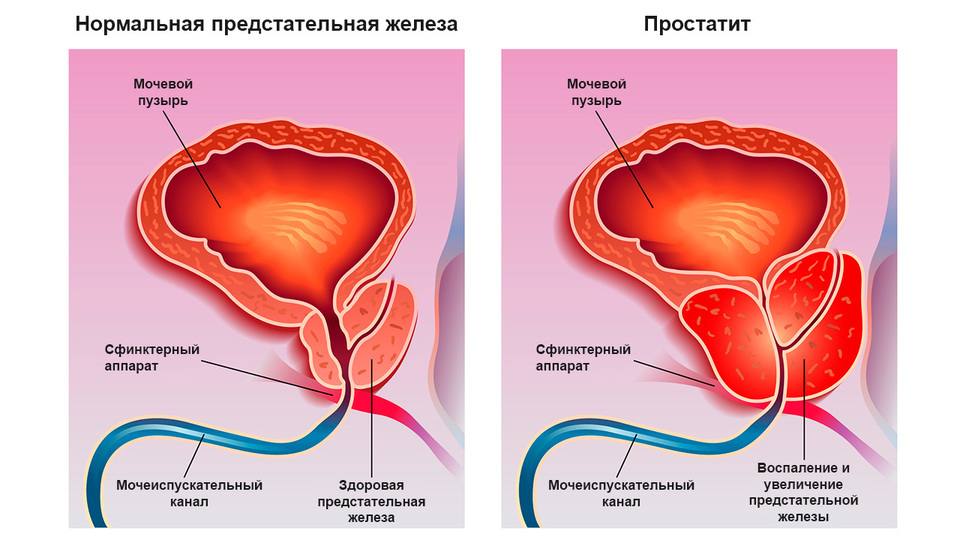

Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate gland. It can be caused by infection with bacteria, or other noninfective causes. Inflammation of the prostate can cause painful urination or ejaculation, groin pain, difficulty passing urine, or constitutional symptoms such as fever or tiredness.[26] When inflamed, the prostate becomes enlarged and is tender when touched during digital rectal examination. The bacteria responsible for the infection may be detected by a urine culture.[26]

Acute prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis are treated with antibiotics.[26] Chronic non-bacterial prostatitis, or male chronic pelvic pain syndrome is treated by a large variety of modalities including the medications alpha blockers, nonsteroidal antiinflammatories and amitriptyline,[26] antihistamines, and other anxiolytics.[27] Other treatments that are not medications may include physical therapy,[28] psychotherapy, nerve modulators, and surgery. More recently, a combination of trigger point and psychological therapy has proved effective for category III prostatitis as well.[27]

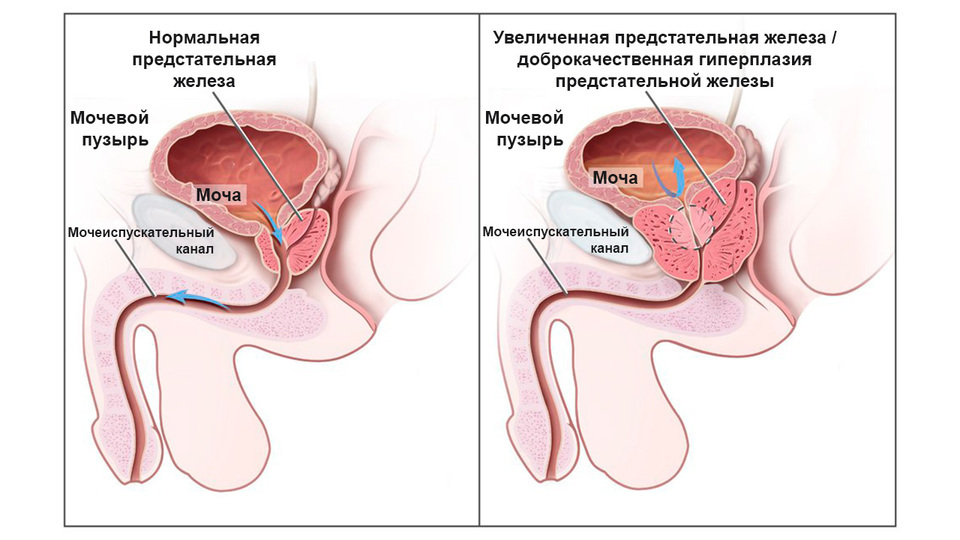

Enlarged prostate[edit]

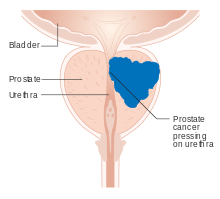

A diagram of prostate cancer pressing on the urethra, which can cause symptoms

An enlarged prostate is called prostatomegaly, with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) being the most common cause. BPH refers to an enlargement of the prostate due to an increase in the number of cells that make up the prostate (hyperplasia) from a cause that is not a malignancy. It is very common in older men.[26] It is often diagnosed when the prostate has enlarged to the point where urination becomes difficult. Symptoms include needing to urinate often (urinary frequency) or taking a while to get started (urinary hesitancy). If the prostate grows too large, it may constrict the urethra and impede the flow of urine, making urination painful and difficult, or in extreme cases completely impossible, causing urinary retention.[26] Over time, chronic retention may cause the bladder to become larger and cause a backflow of urine into the kidneys (hydronephrosis).[26]

BPH can be treated with medication, a minimally invasive procedure or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate. In general, treatment often begins with an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist medication such as tamsulosin, which reduces the tone of the smooth muscle found in the urethra that passes through the prostate, making it easier for urine to pass through.[26] For people with persistent symptoms, procedures may be considered. The surgery most often used in such cases is transurethral resection of the prostate,[26] in which an instrument is inserted through the urethra to remove prostate tissue that is pressing against the upper part of the urethra and restricting the flow of urine. Minimally invasive procedures include transurethral needle ablation of the prostate and transurethral microwave thermotherapy.[29] These outpatient procedures may be followed by the insertion of a temporary stent, to allow normal voluntary urination, without exacerbating irritative symptoms.[30]

Cancer[edit]

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers affecting older men in the UK, US, Northern Europe and Australia, and a significant cause of death for elderly men worldwide.[31] Often, a person does not have symptoms; when they do occur, symptoms may include urinary frequency, urgency, hesitation and other symptoms associated with BPH. Uncommonly, such cancers may cause weight loss, retention of urine, or symptoms such as back pain due to metastatic lesions that have spread outside of the prostate.[26]

A digital rectal examination and the measurement of a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level are usually the first investigations done to check for prostate cancer. PSA values are difficult to interpret, because a high value might be present in a person without cancer, and a low value can be present in someone with cancer.[26] The next form of testing is often the taking of a biopsy to assess for tumour activity and invasiveness.[26] Because of the significant risk of overdiagnosis with widespread screening in the general population, prostate cancer screening is controversial.[32] If a tumour is confirmed, medical imaging such as an MRI or bone scan may be done to check for the presence of tumour metastases in other parts of the body.[26]

Prostate cancer that is only present in the prostate is often treated with either surgical removal of the prostate or with radiotherapy or by the insertion of small radioactive particles of iodine-125 or palladium-103, called brachytherapy.[33][26] Cancer that has spread to other parts of the body is usually treated also with hormone therapy, to deprive a tumour of sex hormones (androgens) that stimulate proliferation. This is often done through the use of GnRH analogues or agents (such as bicalutamide) that block the receptors that androgens act on; occasionally, surgical removal of the testes may be done instead.[26] Cancer that does not respond to hormonal treatment, or that progresses after treatment, might be treated with chemotherapy such as docetaxel. Radiotherapy may also be used to help with pain associated with bony lesions.[26]

Sometimes, the decision may be made not to treat prostate cancer. If a cancer is small and localised, the decision may be made to monitor for cancer activity at intervals («active surveillance») and defer treatment.[26] If a person, because of frailty or other medical conditions or reasons, has a life expectancy less than ten years, then the impacts of treatment may outweigh any perceived benefits.[26]

Surgery[edit]

Surgery to remove the prostate is called prostatectomy, and is usually done as a treatment for cancer limited to the prostate, or prostatic enlargement.[34] When it is done, it may be done as open surgery or as laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery.[34] These are done under general anaesthetic.[35] Usually the procedure for cancer is a radical prostatectomy, which means that the seminal vesicles are removed and vas deferens is also tied off.[34] Part of the prostate can also be removed from within the urethra, called transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).[34] Open surgery may involve a cut that is made in the perineum, or via an approach that involves a cut down the midline from the belly button to the pubic bone.[34] Open surgery may be preferred if there is a suspicion that lymph nodes are involved and they need to be removed or biopsied during a procedure.[34] A perineal approach will not involve lymph node removal and may result in less pain and a faster recovery following an operation.[34] A TURP procedure uses a tube inserted into the urethra via the penis and some form of heat, electricity or laser to remove prostate tissue.[34]

The whole prostate can be removed. Complications that might develop because of surgery include urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction because of damage to nerves during the operation, particularly if a cancer is very close to nerves.[34][35] Ejaculation of semen will not occur during orgasm if the vas deferens are tied off and seminal vesicles removed, such as during a radical prosatectomy.[34] This will mean a man becomes infertile.[34] Sometimes, orgasm may not be able to occur or may be painful. The penis length may change if the part of the urethra within the prostate is also removed.[34] General complications due to surgery can also develop, such as infections, bleeding, inadvertent damage to nearby organs or within the abdomen, and the formation of blood clots.[34]

History[edit]

The prostate was first formally identified by Venetian anatomist Niccolò Massa in Anatomiae libri introductorius (Introduction to Anatomy) 1536 and illustrated by Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius in Tabulae anatomicae sex (six anatomical tables) in 1538.[36][5] Massa described it as a «glandular flesh upon which rests the neck of the bladder,» and Vesalius as a «glandular body».[37] The first time a word similar to ‘prostate’ was used to describe the gland is credited to André du Laurens in 1600, who described it as a term already in use by anatomists at the time.[37][5] The term was however used at least as early as 1549 by French surgeon Ambroise Pare.[5]

At the time, Du Laurens was describing what was considered to be a pair of organs (not the single two-lobed organ), and the Latin term prostatae that was used was a mistranslation of the term for the Ancient Greek word used to describe the seminal vesicles, parastatai;[37] although it has been argued that surgeons in Ancient Greece and Rome must have at least seen the prostate as an anatomical entity.[5] The term prostatae was taken rather than the grammatically correct prostator (singular) and prostatores (plural) because the gender of the Ancient Greek term was taken as female, when it was in fact male.[37]

The fact that the prostate was one and not two organs was an idea popularised throughout the early 18th century, as was the English language term used to describe the organ, prostate,[37] attributed to William Cheselden.[38] A monograph, «Practical observations on the treatment of the diseases of the prostate gland» by Everard Home in 1811, was important in the history of the prostate by describing and naming anatomical parts of the prostate, including the median lobe.[37] The idea of the five lobes of the prostate was popularized following anatomical studies conducted by American urologist Oswald Lowsley in 1912.[5][38] John E. McNeal first proposed the idea of «zones» in 1968; McNeal found that the relatively homogeneous cut surface of an adult prostate in no way resembled «lobes» and thus led to the description of «zones».[39]

Prostate cancer was first described in a speech to the Medical and Chiurgical Society of London in 1853 by surgeon John Adams[40][41] and increasingly described by the late 19th century.[42] Prostate cancer was initially considered a rare disease, probably because of shorter life expectancies and poorer detection methods in the 19th century. The first treatments of prostate cancer were surgeries to relieve urinary obstruction.[43] Samuel David Gross has been credited with the first mention of a prostatectomy, as «too absurd to be seriously entertained»[44][42] The first removal for prostate cancer (radical perineal prostatectomy) was first performed in 1904 by Hugh H. Young at Johns Hopkins Hospital;[45][42] partial removal of the gland was conducted by Theodore Billroth in 1867.[38]

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) replaced radical prostatectomy for symptomatic relief of obstruction in the middle of the 20th century because it could better preserve penile erectile function. Radical retropubic prostatectomy was developed in 1983 by Patrick Walsh.[46] In 1941, Charles B. Huggins published studies in which he used estrogen to oppose testosterone production in men with metastatic prostate cancer. This discovery of «chemical castration» won Huggins the 1966 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[47]

The role of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in reproduction was determined by Andrzej W. Schally and Roger Guillemin, who both won the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work. GnRH receptor agonists, such as leuprorelin and goserelin, were subsequently developed and used to treat prostate cancer.[48][49] Radiation therapy for prostate cancer was first developed in the early 20th century and initially consisted of intraprostatic radium implants. External beam radiotherapy became more popular as stronger X-ray radiation sources became available in the middle of the 20th century. Brachytherapy with implanted seeds (for prostate cancer) was first described in 1983.[50] Systemic chemotherapy for prostate cancer was first studied in the 1970s. The initial regimen of cyclophosphamide and 5-fluorouracil was quickly joined by multiple regimens using a host of other systemic chemotherapy drugs.[51]

Other animals[edit]

The prostate is found only in mammals.[52] The prostate glands of male marsupials are proportionally larger than those of placental mammals.[53] The presence of a functional prostate in monotremes is controversial, and if monotremes do possess functional prostates, they may not make the same contribution to semen as in other mammals.[54]

The structure of the prostate varies, ranging from tubuloalveolar (as in humans) to branched tubular. The gland is particularly well developed in dogs, foxes and boars, though in other mammals, such as bulls, it can be small and inconspicuous.[55][56][57] In other animals, such as marsupials[58][59] and small ruminants, the prostate is disseminate, meaning not specifically localisable as a distinct tissue, but present throughout the relevant part of the urethra; in other animals, such as red deer and American elk, it may be present as a specific organ and in a disseminate form.[60] In some marsupial species, the size of the prostate gland changes seasonally.[61] The prostate is the only accessory gland that occurs in male dogs.[62] Dogs can produce in one hour as much prostatic fluid as a human can in a day. They excrete this fluid along with their urine to mark their territory.[63] Additionally, dogs are the only species apart from humans seen to have a significant incidence of prostate cancer.[64] In cetaceans (whales, dolphins, porpoises) the prostate is composed of diffuse urethral glands[65] and is surrounded by a very powerful compressor muscle.[66]

The prostate gland originates with tissues in the urethral wall.[citation needed] This means the urethra, a compressible tube used for urination, runs through the middle of the prostate. This leads to an evolutionary design fault for some mammals, including human males. The prostate is prone to infection and enlargement later in life, constricting the urethra so urinating becomes slow and painful.[67]

Prostatic secretions vary among species. They are generally composed of simple sugars and are often slightly alkaline.[68]

Skene’s gland[edit]

Because the Skene’s gland and the male prostate act similarly by secreting prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which is an ejaculate protein produced in males, and of prostate-specific acid phosphatase, the Skene’s gland is sometimes referred to as the «female prostate».[69][70] Although it is homologous to the male prostate (developed from the same embryological tissues),[71][72] various aspects of its development in relation to the male prostate are widely unknown and a matter of research.[73]

See also[edit]

- Ejaculatory duct

- Seminal vesicles

- Prostate evolution in monotreme mammals

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Vásquez, Bélgica (2014-03-01). «Morphological Characteristics of Prostate in Mammals». International Journal of Medical and Surgical Sciences. 1 (1): 63–72. doi:10.32457/ijmss.2014.010. ISSN 0719-532X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Young, Barbara; O’Dowd, Geraldine; Woodford, Phillip (2013). Wheater’s functional histology: a text and colour atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 347–8. ISBN 9780702047473.

- ^ Leissner KH, Tisell LE (1979). «The weight of the human prostate». Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 13 (2): 137–42. doi:10.3109/00365597909181168. PMID 90380.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Standring, Susan, ed. (2016). «Prostate». Gray’s anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia. pp. 1266–1270. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goddard, Jonathan Charles (January 2019). «The history of the prostate, part one: say what you see». Trends in Urology & Men’s Health. 10 (1): 28–30. doi:10.1002/tre.676.

- ^ a b «Basic Principles: Prostate Anatomy» Archived 2010-10-15 at the Wayback Machine. Urology Match. Www.urologymatch.com. Web. 14 June 2010.

- ^ a b «Prostate Cancer Information from the Foundation of the Prostate Gland.» Prostate Cancer Treatment Guide. Web. 14 June 2010.

- ^ Cohen RJ, Shannon BA, Phillips M, Moorin RE, Wheeler TM, Garrett KL (2008). «Central zone carcinoma of the prostate gland: a distinct tumor type with poor prognostic features». The Journal of Urology. 179 (5): 1762–7, discussion 1767. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.017. PMID 18343454.

- ^ a b Michael Schünke, Erik Schulte, Udo Schumacher: PROMETHEUS Innere Organe. LernAtlas Anatomie, vol 2: Innere Organe, Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart/Germany 2012, ISBN 9783131395337, p. 298, PDF.

- ^ «Prostate Gland Development». ana.ed.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2003-04-30. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- ^ «Prostate». webpath.med.utah.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- ^ «The human proteome in prostate – The Human Protein Atlas». www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- ^ Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). «Tissue-based map of the human proteome». Science. 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- ^ O’Hurley, Gillian; Busch, Christer; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Stadler, Charlotte; Tolf, Anna; Lundberg, Emma; Schwenk, Jochen M.; Jirström, Karin (2015-08-03). «Analysis of the Human Prostate-Specific Proteome Defined by Transcriptomics and Antibody-Based Profiling Identifies TMEM79 and ACOXL as Two Putative, Diagnostic Markers in Prostate Cancer». PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0133449. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1033449O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133449. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4523174. PMID 26237329.

- ^ Kong, HY; Byun, J (January 2013). «Emerging roles of human prostatic Acid phosphatase». Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 21 (1): 10–20. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2012.095. PMC 3762301. PMID 24009853.

- ^ a b Sadley, TW (2019). «Bladder and urethra». Langman’s medical embryology (14th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 263–66. ISBN 9781496383907.

- ^ a b c Sadley, TW (2019). Langman’s medical embryology (14th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 265–6. ISBN 9781496383907.

- ^ Moore, Keith L.; Persaud, T. V. N.; Torchia, Mark G. (2008). Before We are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects (7th ed.). ISBN 978-1-4160-3705-7.

- ^ a b c d e Barrett, Kim E. (2019). Ganong’s review of medical physiology. Barman, Susan M.,, Brooks, Heddwen L.,, Yuan, Jason X.-J. (26th ed.). New York. pp. 411, 415. ISBN 9781260122404. OCLC 1076268769.

- ^ Rosenthal, Martha (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. pp. 133–135. ISBN 978-0618755714. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Komisaruk, Barry R.; Whipple, Beverly; Nasserzadeh, Sara & Beyer-Flores, Carlos (2009). The Orgasm Answer Guide. JHU Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8018-9396-4. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Levin, R. J. (2018). «Prostate-induced orgasms: A concise review illustrated with a highly relevant case study». Clinical Anatomy. 31 (1): 81–85. doi:10.1002/ca.23006. PMID 29265651.

- ^ Hocaoglu Y, Roosen A, Herrmann K, Tritschler S, Stief C, Bauer RM (2012). «Real-time magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): anatomical changes during physiological voiding in men». BJU Int. 109 (2): 234–9. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10255.x. PMID 21736694.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hocaoglu Y, Herrmann K, Walther S, Hennenberg M, Gratzke C, Bauer R; et al. (2013). «Contraction of the anterior prostate is required for the initiation of micturition». BJU Int. 111 (7): 1117–23. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11698.x. PMID 23356864.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lebdai S, Chevrot A, Doizi S, Pradere B, Delongchamps NB, Benchikh A; et al. (2019). «Do patients have to choose between ejaculation and miction? A systematic review about ejaculation preservation technics for benign prostatic obstruction surgical treatment» (PDF). World J Urol. 37 (2): 299–308. doi:10.1007/s00345-018-2368-6. PMID 29967947. S2CID 49556196. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-11. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Davidson’s 2018, pp. 437–9.

- ^ a b Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan CA (2006). «Sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: improvement after trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training». J. Urol. 176 (4 Pt 1): 1534–8, discussion 1538–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.383.7495. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.010. PMID 16952676.

- ^ «Physical Therapy Treatment for Prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome». 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ^ Christensen, TL; Andriole, GL (February 2009). «Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Current Treatment Strategies». Consultant. 49 (2).

- ^ Dineen MK, Shore ND, Lumerman JH, Saslawsky MJ, Corica AP (2008). «Use of a Temporary Prostatic Stent After Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy Reduced Voiding Symptoms and Bother Without Exacerbating Irritative Symptoms». J. Urol. 71 (5): 873–877. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.015. PMID 18374395.

- ^ Rawla P (April 2019). «Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer». World J Oncol (Review). 10 (2): 63–89. doi:10.14740/wjon1191. PMC 6497009. PMID 31068988.

- ^ Sandhu, Gurdarshan S.; Andriole, Gerald L. (September 2012). «Overdiagnosis of Prostate Cancer». Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 2012 (45): 146–151. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs031. ISSN 1052-6773. PMC 3540879. PMID 23271765.

- ^ «What is Brachytherapy?». American Brachytherapy Society. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m «Surgery for Prostate Cancer». www.cancer.org. The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b «Surgery to remove your prostate gland | Prostate cancer | Cancer Research UK». www.cancerresearchuk.org. Cancer Research UK. 18 Jun 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Ghabili, Kamyar; Tosoian, Jeffrey J.; Schaeffer, Edward M.; Pavlovich, Christian P.; Golzari, Samad E.J.; Khajir, Ghazal; Andreas, Darian; Benzon, Benjamin; Vuica-Ross, Milena; Ross, Ashley E. (November 2016). «The History of Prostate Cancer From Antiquity: Review of Paleopathological Studies». Urology. 97: 8–12. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2016.08.032. PMID 27591810.

- ^ a b c d e f Josef Marx, Franz; Karenberg, Axel (1 February 2009). «History of the Term Prostate». The Prostate. 69 (2): 208–213. doi:10.1002/pros.20871. PMID 18942121. S2CID 44922919.

- ^ a b c Young, Robert H; Eble, John N (January 2019). «The history of urologic pathology: an overview». Histopathology. 74 (1): 184–212. doi:10.1111/his.13753. PMID 30565309. S2CID 56476748.

- ^ Myers, Robert P (2000). «Structure of the adult prostate from a clinician’s standpoint». Clinical Anatomy. 13 (3): 214–5. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(2000)13:3<214::AID-CA10>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 10797630. S2CID 33861863.

- ^ Adams J (1853). «The case of scirrhous of the prostate gland with corresponding affliction of the lymphatic glands in the lumbar region and in the pelvis». Lancet. 1 (1547): 393–94. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)68759-8.

- ^ Ghabili K, Tosoian JJ, Schaeffer EM, Pavlovich CP, Golzari SE, Khajir G, Andreas D, Benzon B, Vuica-Ross M, Ross AE (November 2016). «The History of Prostate Cancer From Antiquity: Review of Paleopathological Studies». Urology. 97: 8–12. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2016.08.032. PMID 27591810.

- ^ a b c Nahon, I; Waddington, G; Dorey, G; Adams, R (2011). «The history of urologic surgery: from reeds to robotics». Urologic Nursing. 31 (3): 173–80. doi:10.7257/1053-816X.2011.31.3.173. PMID 21805756.

- ^ Lytton B (June 2001). «Prostate cancer: a brief history and the discovery of hormonal ablation treatment». The Journal of Urology. 165 (6 Pt 1): 1859–62. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66228-3. PMID 11371867.

- ^ Samuel David Gross (1851). A Practical Treatise On the Diseases and Injuries of the Urinary Bladder, the Prostate Gland, and the Urethra. Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea.

«The idea of extirpating the entire gland is, indeed, too absurd to be seriously entertained… Excision of the middle lobe would be far less objectionable»

- ^ Young HH (1905). «Four cases of radical prostatectomy». Johns Hopkins Bull. 16.

- ^ Walsh PC, Lepor H, Eggleston JC (1983). «Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: anatomical and pathological considerations». The Prostate. 4 (5): 473–85. doi:10.1002/pros.2990040506. PMID 6889192. S2CID 30740301.

- ^ Huggins CB, Hodges CV (1941). «Studies on prostate cancer: 1. The effects of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate». Cancer Res. 1 (4): 293. Archived from the original on 2017-06-30.

- ^ Schally AV, Kastin AJ, Arimura A (November 1971). «Hypothalamic follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH)-regulating hormone: structure, physiology, and clinical studies». Fertility and Sterility. 22 (11): 703–21. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)38580-6. PMID 4941683.

- ^ Tolis G, Ackman D, Stellos A, Mehta A, Labrie F, Fazekas AT, et al. (March 1982). «Tumor growth inhibition in patients with prostatic carcinoma treated with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 79 (5): 1658–62. Bibcode:1982PNAS…79.1658T. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.5.1658. PMC 346035. PMID 6461861.

- ^ Denmeade SR, Isaacs JT (May 2002). «A history of prostate cancer treatment». Nature Reviews. Cancer. 2 (5): 389–96. doi:10.1038/nrc801. PMC 4124639. PMID 12044015.

- ^ Scott WW, Johnson DE, Schmidt JE, Gibbons RP, Prout GR, Joiner JR, et al. (December 1975). «Chemotherapy of advanced prostatic carcinoma with cyclophosphamide or 5-fluorouracil: results of first national randomized study». The Journal of Urology. 114 (6): 909–11. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)67172-6. PMID 1104900.

- ^ Marker, Paul C; Donjacour, Annemarie A; Dahiya, Rajvir; Cunha, Gerald R (January 2003). «Hormonal, cellular, and molecular control of prostatic development». Developmental Biology. 253 (2): 165–174. doi:10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00031-3. PMID 12645922.

- ^ Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe; Marilyn Renfree (30 January 1987). Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33792-2.

- ^ Temple-Smith, P; Grant, T (2001). «Uncertain breeding: a short history of reproduction in monotremes». Reproduction, Fertility, and Development. 13 (7–8): 487–97. doi:10.1071/rd01110. PMID 11999298.

- ^ Sherwood, Lauralee; Klandorf, Hillar; Yancey, Paul (January 2012). Animal Physiology: From Genes to Organisms. p. 779. ISBN 9781133709510.

- ^ Nelsen, O. E. (1953) Comparative embryology of the vertebrates Blakiston, page 31.

- ^ Hafez, E. S. E.; Hafez, B. (2013). Reproduction in Farm Animals. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-71028-9.

- ^ Vogelnest, Larry; Portas, Timothy (2019-05-01). Current Therapy in Medicine of Australian Mammals. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4863-0753-1.

- ^ Society, Australian Mammal (December 1978). Australian Mammal Society. Australian Mammal Society.

- ^ Chenoweth, Peter J.; Lorton, Steven (2014). Animal Andrology: Theories and Applications. CABI. ISBN 978-1-78064-316-8.

- ^ C. Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe (2005). Life of Marsupials. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-06257-3.

- ^ John W. Hermanson; Howard E. Evans; Alexander de Lahunta (20 December 2018). Miller and Evans’ Anatomy of the Dog – E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-323-54602-7.

- ^ Glover, Tim (2012-07-12). Mating Males: An Evolutionary Perspective on Mammalian Reproduction. p. 31. ISBN 9781107000018.

- ^ Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (24 December 2009). Textbook of veterinary internal medicine : diseases of the dog and the cat (7th ed.). St. Louis, Mo. p. 2057. ISBN 9781437702828.

- ^ William F. Perrin; Bernd Würsig; J.G.M. Thewissen (26 February 2009). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- ^ Rommel, Sentiel A., D. Ann Pabst, and William A. McLellan. «Functional anatomy of the cetacean reproductive system, with comparisons to the domestic dog.» Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Cetacea. Science Publishers (2016): 127–145.

- ^ Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why Evolution is True. p. 90. ISBN 9780199230846.

- ^ Alan J., Wein; Louis R., Kavoussi; Alan W., Partin; Craig A., Peters (23 October 2015). Campbell-Walsh Urology (Eleventh ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1005–. ISBN 9780323263740.

- ^ Pastor Z, Chmel R (2017). «Differential diagnostics of female «sexual» fluids: a narrative review». International Urogynecology Journal. 29 (5): 621–629. doi:10.1007/s00192-017-3527-9. PMID 29285596. S2CID 5045626.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Bullough, Vern L.; Bullough, Bonnie (2014). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 231. ISBN 978-1135825096.

- ^ Lentz, Gretchen M; Lobo, Rogerio A.; Gershenson, David M; Katz, Vern L. (2012). Comprehensive Gynecology. Elsevier Health Sciences, Philadelphia. p. 41. ISBN 978-0323091312.

- ^ Hornstein, Theresa; Schwerin, Jeri Lynn (2013). Biology of women. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar, Cengage Learning. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-285-40102-7. OCLC 911037670.

- ^ Toivanen R, Shen MM (2017). «Prostate organogenesis: tissue induction, hormonal regulation and cell type specification». Development. 144 (8): 1382–1398. doi:10.1242/dev.148270. PMC 5399670. PMID 28400434.

General and cited sources[edit]

- Ralston, Stuart H.; Penman, Ian D.; Strachan, Mark W.; Hobson, Richard P., eds. (2018). Davidson’s principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

- Attribution

- Portions of the text of this article originate from NIH Publication No. 02-4806, a public domain resource. «What I need to know about Prostate Problems». National Institutes of Health. 2002-06-01. No. 02-4806. Archived from the original on 2002-06-01. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

External links[edit]

Media related to Prostate at Wikimedia Commons

This article is about the male prostate gland. For the equivalent female prostate gland, see Skene’s gland. For the journal, see The Prostate.

| Prostate | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Details | |

| Precursor | Endodermic evaginations of the urethra |

| Artery | Internal pudendal artery, inferior vesical artery, and middle rectal artery |

| Vein | Prostatic venous plexus, pudendal plexus, vesical plexus, internal iliac vein |

| Nerve | Inferior hypogastric plexus |

| Lymph | internal iliac lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Prostata |

| MeSH | D011467 |

| TA98 | A09.3.08.001 |

| TA2 | 3637 |

| FMA | 9600 |

| Anatomical terminology

[edit on Wikidata] |

The prostate is both an accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found in all male mammals.[1] It differs between species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically. Anatomically, the prostate is found below the bladder, with the urethra passing through it. It is described in gross anatomy as consisting of lobes and in microanatomy by zone. It is surrounded by an elastic, fibromuscular capsule and contains glandular tissue as well as connective tissue.

The prostate glands produce and contain fluid that forms part of semen, the substance emitted during ejaculation as part of the male sexual response. This prostatic fluid is slightly alkaline, milky or white in appearance. The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm. The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first part of ejaculate, together with most of the sperm, because of the action of smooth muscle tissue within the prostate. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid, those in prostatic fluid have better motility, longer survival, and better protection of genetic material.

Disorders of the prostate include enlargement, inflammation, infection, and cancer. The word prostate comes from Ancient Greek προστάτης, prostátēs, meaning «one who stands before», «protector», «guardian», with the term originally used to describe the seminal vesicles.

Structure[edit]

The prostate is a gland of the male reproductive system. In adults, it is about the size of a walnut,[2] and has an average weight of about 11 grams, usually ranging between 7 and 16 grams.[3] The prostate is located in the pelvis. It sits below the urinary bladder and surrounds the urethra. The part of the urethra passing through it is called the prostatic urethra, which joins with the two ejaculatory ducts.[2] The prostate is covered in a surface called the prostatic capsule or prostatic fascia.[4]

The internal structure of the prostate has been described using both lobes and zones.[5][2] Because of the variation in descriptions and definitions of lobes, the zone classification is used more predominantly.[2]

The prostate has been described as consisting of three or four zones.[2][4] Zones are more typically able to be seen on histology, or in medical imaging, such as ultrasound or MRI.[2][5] The zones are:

| Name | Fraction of adult gland[2] | Description |

| Peripheral zone (PZ) | 70% | The back of the gland that surrounds the distal urethra and lies beneath the capsule. About 70–80% of prostatic cancers originate from this zone of the gland.[6][7] |

| Central zone (CZ) | 20% | This zone surrounds the ejaculatory ducts.[2] The central zone accounts for roughly 2.5% of prostate cancers; these cancers tend to be more aggressive and more likely to invade the seminal vesicles.[8] |

| Transition zone (TZ) | 5% | The transition zone surrounds the proximal urethra.[2] ~10–20% of prostate cancers originate in this zone. It is the region of the prostate gland that grows throughout life and causes the disease of benign prostatic enlargement.[6][7] |

| Anterior fibro-muscular zone (or stroma) | N/A | This area, not always considered a zone,[4] is usually devoid of glandular components and composed only, as its name suggests, of muscle and fibrous tissue.[2] |

The «lobe» classification describes lobes that, while originally defined in the fetus, are also visible in gross anatomy, including dissection and when viewed endoscopically.[5][4] The five lobes are the anterior lobe or isthmus, the posterior lobe, the right and left lateral lobes, and the middle or median lobe.

-

Lobes of prostate

-

Zones of prostate

Inside of the prostate, adjacent and parallel to the prostatic urethra, there are two longitudinal muscle systems. On the front side (ventrally) runs the urethral dilator (musculus dilatator urethrae), on the backside (dorsally) runs the muscle switching the urethra into the ejaculatory state (musculus ejaculatorius).[9]

Blood and lymphatic vessels[edit]

The prostate receives blood through the inferior vesical artery, internal pudendal artery, and middle rectal arteries. These vessels enter the prostate on its outer posterior surface where it meets the bladder, and travel forward to the apex of the prostate.[4] Both the inferior vesical and the middle rectal arteries often arise together directly from the internal iliac arteries. On entering the bladder, the inferior vesical artery splits into a urethral branch, supplying the urethral prostate; and a capsular branch, which travels around the capsule and has smaller branches which perforate into the prostate.[4]

The veins of the prostate form a network – the prostatic venous plexus, primarily around its front and outer surface.[4] This network also receives blood from the deep dorsal vein of the penis, and is connected via branches to the vesical plexus and internal pudendal veins.[4] Veins drain into the vesical and then internal iliac veins.[4]

The lymphatic drainage of the prostate depends on the positioning of the area. Vessels surrounding the vas deferens, some of the vessels in the seminal vesicle, and a vessel from the posterior surface of the prostate drain into the external iliac lymph nodes.[4] Some of the seminal vesicle vessels, prostatic vessels, and vessels from the anterior prostate drain into internal iliac lymph nodes.[4] Vessels of the prostate itself also drain into the obturator and sacral lymph nodes.[4]

Microanatomy[edit]

The prostate consists of glandular and connective tissue.[2] Tall column-shaped cells form the lining (the epithelium) of the glands.[2] These form one layer or may be pseudostratified.[4] The epithelium is highly variable and areas of low cuboidal or flat cells can also be present, with transitional epithelium in the outer regions of the longer ducts.[10] The glands are formed as many follicles, which in drain into canals and subsequently 12–20 main ducts, These in turn drain into the urethra as it passes through the prostate.[4] There are also a small amount of flat cells, which sit next to the basement membranes of glands, and act as stem cells.[2]

The connective tissue of the prostate is made up of fibrous tissue and smooth muscle.[2] The fibrous tissue separates the gland into lobules.[2] It also sits between the glands and is composed of randomly orientated smooth-muscle bundles that are continuous with the bladder.[11]

Over time, thickened secretions called corpora amylacea accumulate in the gland.[2]

-

Microscopic glands of the prostate

Gene and protein expression[edit]

About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and almost 75% of these genes are expressed in the normal prostate.[12][13] About 150 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the prostate, with about 20 genes being highly prostate specific.[14] The corresponding specific proteins are expressed in the glandular and secretory cells of the prostatic gland and have functions that are important for the characteristics of semen, including prostate-specific proteins, such as the prostate specific antigen (PSA), and the Prostatic acid phosphatase.[15]

Development[edit]

In the developing embryo, at the hind end lies an inpouching called the cloaca. This, over the fourth to the seventh week, divides into a urogenital sinus and the beginnings of the anal canal, with a wall forming between these two inpouchings called the urorectal septum.[16] The urogenital sinus divides into three parts, with the middle part forming the urethra; the upper part is largest and becomes the urinary bladder, and the lower part then changes depending on the biological sex of the embryo.[16]

The prostatic part of the urethra develops from the middle, pelvic, part of the urogenital sinus, which is of endodermal origin.[17] Around the end of the third month of embryonic life, outgrowths arise from the prostatic part of the urethra and grow into the surrounding mesenchyme.[17] The cells lining this part of the urethra differentiate into the glandular epithelium of the prostate.[17] The associated mesenchyme differentiates into the dense connective tissue and the smooth muscle of the prostate.[18]

Condensation of mesenchyme, urethra, and Wolffian ducts gives rise to the adult prostate gland, a composite organ made up of several tightly fused glandular and non-glandular components. To function properly, the prostate needs male hormones (androgens), which are responsible for male sex characteristics. The main male hormone is testosterone, which is produced mainly by the testicles. It is dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a metabolite of testosterone, that predominantly regulates the prostate. The prostate gland enlarges over time, until the fourth decade of life.[4]

Function[edit]

The prostate secretes fluid which becomes part of semen. Semen is the fluid emitted (ejaculated) by males during the sexual response.[19] When sperm is emitted, it is transmitted from the vas deferens into the male urethra via the ejaculatory ducts, which lie within the prostate gland.[19] Ejaculation is the expulsion of semen from the urethra.[19] Semen is moved into the urethra following contractions of the smooth muscle of the vas deferens and seminal vesicles, following stimulation, primarily of the glans penis. Stimulation sends nerve signals via the internal pudendal nerves to the upper lumbar spine; the nerve signals causing contraction act via the hypogastric nerves.[19] After traveling into the urethra, the seminal fluid is ejaculated by contraction of the bulbocavernosus muscle.[19] The secretions of the prostate include proteolytic enzymes, prostatic acid phosphatase, fibrinolysin, zinc, and prostate-specific antigen.[4] Together with the secretions from the seminal vesicles, these form the major fluid part of semen.[4]

It is possible for some men to achieve orgasm solely through stimulation of the prostate gland, such as via prostate massage or anal intercourse.[20][21] This has led to the area of the rectal wall adjacent to the prostate to be popularly referred by the anatomically incorrect term, the «male G-spot».[22]

The prostate’s changes of shape, which facilitate the mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation, are mainly driven by the two longitudinal muscle systems running along the prostatic urethra. These are the urethral dilator (musculus dilatator urethrae) on the urethra’s front side, which contracts during urination and thereby shortens and tilts the prostate in its vertical dimension thus widening the prostatic section of the urethral tube,[23][24] and the muscle switching the urethra into the ejaculatory state (musculus ejaculatorius) on its backside.[9]

In case of an operation, e.g. because of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), damaging or sparing of these two muscle systems varies considerably depending on the choice of operation type and details of the procedure of the chosen technique. The effects on postoperational urination and ejaculation vary correspondingly.[25] (See also: Surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia).

Clinical significance[edit]

Inflammation[edit]

Micrograph showing an inflamed prostate gland, found in prostatitis. A large amount of darker cells, representing leukocytes, can be seen. An area without inflammation is seen on the left of the image. H&E stain.

Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate gland. It can be caused by infection with bacteria, or other noninfective causes. Inflammation of the prostate can cause painful urination or ejaculation, groin pain, difficulty passing urine, or constitutional symptoms such as fever or tiredness.[26] When inflamed, the prostate becomes enlarged and is tender when touched during digital rectal examination. The bacteria responsible for the infection may be detected by a urine culture.[26]

Acute prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis are treated with antibiotics.[26] Chronic non-bacterial prostatitis, or male chronic pelvic pain syndrome is treated by a large variety of modalities including the medications alpha blockers, nonsteroidal antiinflammatories and amitriptyline,[26] antihistamines, and other anxiolytics.[27] Other treatments that are not medications may include physical therapy,[28] psychotherapy, nerve modulators, and surgery. More recently, a combination of trigger point and psychological therapy has proved effective for category III prostatitis as well.[27]

Enlarged prostate[edit]

A diagram of prostate cancer pressing on the urethra, which can cause symptoms

An enlarged prostate is called prostatomegaly, with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) being the most common cause. BPH refers to an enlargement of the prostate due to an increase in the number of cells that make up the prostate (hyperplasia) from a cause that is not a malignancy. It is very common in older men.[26] It is often diagnosed when the prostate has enlarged to the point where urination becomes difficult. Symptoms include needing to urinate often (urinary frequency) or taking a while to get started (urinary hesitancy). If the prostate grows too large, it may constrict the urethra and impede the flow of urine, making urination painful and difficult, or in extreme cases completely impossible, causing urinary retention.[26] Over time, chronic retention may cause the bladder to become larger and cause a backflow of urine into the kidneys (hydronephrosis).[26]

BPH can be treated with medication, a minimally invasive procedure or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate. In general, treatment often begins with an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist medication such as tamsulosin, which reduces the tone of the smooth muscle found in the urethra that passes through the prostate, making it easier for urine to pass through.[26] For people with persistent symptoms, procedures may be considered. The surgery most often used in such cases is transurethral resection of the prostate,[26] in which an instrument is inserted through the urethra to remove prostate tissue that is pressing against the upper part of the urethra and restricting the flow of urine. Minimally invasive procedures include transurethral needle ablation of the prostate and transurethral microwave thermotherapy.[29] These outpatient procedures may be followed by the insertion of a temporary stent, to allow normal voluntary urination, without exacerbating irritative symptoms.[30]

Cancer[edit]

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers affecting older men in the UK, US, Northern Europe and Australia, and a significant cause of death for elderly men worldwide.[31] Often, a person does not have symptoms; when they do occur, symptoms may include urinary frequency, urgency, hesitation and other symptoms associated with BPH. Uncommonly, such cancers may cause weight loss, retention of urine, or symptoms such as back pain due to metastatic lesions that have spread outside of the prostate.[26]

A digital rectal examination and the measurement of a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level are usually the first investigations done to check for prostate cancer. PSA values are difficult to interpret, because a high value might be present in a person without cancer, and a low value can be present in someone with cancer.[26] The next form of testing is often the taking of a biopsy to assess for tumour activity and invasiveness.[26] Because of the significant risk of overdiagnosis with widespread screening in the general population, prostate cancer screening is controversial.[32] If a tumour is confirmed, medical imaging such as an MRI or bone scan may be done to check for the presence of tumour metastases in other parts of the body.[26]

Prostate cancer that is only present in the prostate is often treated with either surgical removal of the prostate or with radiotherapy or by the insertion of small radioactive particles of iodine-125 or palladium-103, called brachytherapy.[33][26] Cancer that has spread to other parts of the body is usually treated also with hormone therapy, to deprive a tumour of sex hormones (androgens) that stimulate proliferation. This is often done through the use of GnRH analogues or agents (such as bicalutamide) that block the receptors that androgens act on; occasionally, surgical removal of the testes may be done instead.[26] Cancer that does not respond to hormonal treatment, or that progresses after treatment, might be treated with chemotherapy such as docetaxel. Radiotherapy may also be used to help with pain associated with bony lesions.[26]

Sometimes, the decision may be made not to treat prostate cancer. If a cancer is small and localised, the decision may be made to monitor for cancer activity at intervals («active surveillance») and defer treatment.[26] If a person, because of frailty or other medical conditions or reasons, has a life expectancy less than ten years, then the impacts of treatment may outweigh any perceived benefits.[26]

Surgery[edit]

Surgery to remove the prostate is called prostatectomy, and is usually done as a treatment for cancer limited to the prostate, or prostatic enlargement.[34] When it is done, it may be done as open surgery or as laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery.[34] These are done under general anaesthetic.[35] Usually the procedure for cancer is a radical prostatectomy, which means that the seminal vesicles are removed and vas deferens is also tied off.[34] Part of the prostate can also be removed from within the urethra, called transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).[34] Open surgery may involve a cut that is made in the perineum, or via an approach that involves a cut down the midline from the belly button to the pubic bone.[34] Open surgery may be preferred if there is a suspicion that lymph nodes are involved and they need to be removed or biopsied during a procedure.[34] A perineal approach will not involve lymph node removal and may result in less pain and a faster recovery following an operation.[34] A TURP procedure uses a tube inserted into the urethra via the penis and some form of heat, electricity or laser to remove prostate tissue.[34]

The whole prostate can be removed. Complications that might develop because of surgery include urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction because of damage to nerves during the operation, particularly if a cancer is very close to nerves.[34][35] Ejaculation of semen will not occur during orgasm if the vas deferens are tied off and seminal vesicles removed, such as during a radical prosatectomy.[34] This will mean a man becomes infertile.[34] Sometimes, orgasm may not be able to occur or may be painful. The penis length may change if the part of the urethra within the prostate is also removed.[34] General complications due to surgery can also develop, such as infections, bleeding, inadvertent damage to nearby organs or within the abdomen, and the formation of blood clots.[34]

History[edit]

The prostate was first formally identified by Venetian anatomist Niccolò Massa in Anatomiae libri introductorius (Introduction to Anatomy) 1536 and illustrated by Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius in Tabulae anatomicae sex (six anatomical tables) in 1538.[36][5] Massa described it as a «glandular flesh upon which rests the neck of the bladder,» and Vesalius as a «glandular body».[37] The first time a word similar to ‘prostate’ was used to describe the gland is credited to André du Laurens in 1600, who described it as a term already in use by anatomists at the time.[37][5] The term was however used at least as early as 1549 by French surgeon Ambroise Pare.[5]

At the time, Du Laurens was describing what was considered to be a pair of organs (not the single two-lobed organ), and the Latin term prostatae that was used was a mistranslation of the term for the Ancient Greek word used to describe the seminal vesicles, parastatai;[37] although it has been argued that surgeons in Ancient Greece and Rome must have at least seen the prostate as an anatomical entity.[5] The term prostatae was taken rather than the grammatically correct prostator (singular) and prostatores (plural) because the gender of the Ancient Greek term was taken as female, when it was in fact male.[37]

The fact that the prostate was one and not two organs was an idea popularised throughout the early 18th century, as was the English language term used to describe the organ, prostate,[37] attributed to William Cheselden.[38] A monograph, «Practical observations on the treatment of the diseases of the prostate gland» by Everard Home in 1811, was important in the history of the prostate by describing and naming anatomical parts of the prostate, including the median lobe.[37] The idea of the five lobes of the prostate was popularized following anatomical studies conducted by American urologist Oswald Lowsley in 1912.[5][38] John E. McNeal first proposed the idea of «zones» in 1968; McNeal found that the relatively homogeneous cut surface of an adult prostate in no way resembled «lobes» and thus led to the description of «zones».[39]

Prostate cancer was first described in a speech to the Medical and Chiurgical Society of London in 1853 by surgeon John Adams[40][41] and increasingly described by the late 19th century.[42] Prostate cancer was initially considered a rare disease, probably because of shorter life expectancies and poorer detection methods in the 19th century. The first treatments of prostate cancer were surgeries to relieve urinary obstruction.[43] Samuel David Gross has been credited with the first mention of a prostatectomy, as «too absurd to be seriously entertained»[44][42] The first removal for prostate cancer (radical perineal prostatectomy) was first performed in 1904 by Hugh H. Young at Johns Hopkins Hospital;[45][42] partial removal of the gland was conducted by Theodore Billroth in 1867.[38]

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) replaced radical prostatectomy for symptomatic relief of obstruction in the middle of the 20th century because it could better preserve penile erectile function. Radical retropubic prostatectomy was developed in 1983 by Patrick Walsh.[46] In 1941, Charles B. Huggins published studies in which he used estrogen to oppose testosterone production in men with metastatic prostate cancer. This discovery of «chemical castration» won Huggins the 1966 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[47]

The role of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) in reproduction was determined by Andrzej W. Schally and Roger Guillemin, who both won the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this work. GnRH receptor agonists, such as leuprorelin and goserelin, were subsequently developed and used to treat prostate cancer.[48][49] Radiation therapy for prostate cancer was first developed in the early 20th century and initially consisted of intraprostatic radium implants. External beam radiotherapy became more popular as stronger X-ray radiation sources became available in the middle of the 20th century. Brachytherapy with implanted seeds (for prostate cancer) was first described in 1983.[50] Systemic chemotherapy for prostate cancer was first studied in the 1970s. The initial regimen of cyclophosphamide and 5-fluorouracil was quickly joined by multiple regimens using a host of other systemic chemotherapy drugs.[51]

Other animals[edit]

The prostate is found only in mammals.[52] The prostate glands of male marsupials are proportionally larger than those of placental mammals.[53] The presence of a functional prostate in monotremes is controversial, and if monotremes do possess functional prostates, they may not make the same contribution to semen as in other mammals.[54]

The structure of the prostate varies, ranging from tubuloalveolar (as in humans) to branched tubular. The gland is particularly well developed in dogs, foxes and boars, though in other mammals, such as bulls, it can be small and inconspicuous.[55][56][57] In other animals, such as marsupials[58][59] and small ruminants, the prostate is disseminate, meaning not specifically localisable as a distinct tissue, but present throughout the relevant part of the urethra; in other animals, such as red deer and American elk, it may be present as a specific organ and in a disseminate form.[60] In some marsupial species, the size of the prostate gland changes seasonally.[61] The prostate is the only accessory gland that occurs in male dogs.[62] Dogs can produce in one hour as much prostatic fluid as a human can in a day. They excrete this fluid along with their urine to mark their territory.[63] Additionally, dogs are the only species apart from humans seen to have a significant incidence of prostate cancer.[64] In cetaceans (whales, dolphins, porpoises) the prostate is composed of diffuse urethral glands[65] and is surrounded by a very powerful compressor muscle.[66]

The prostate gland originates with tissues in the urethral wall.[citation needed] This means the urethra, a compressible tube used for urination, runs through the middle of the prostate. This leads to an evolutionary design fault for some mammals, including human males. The prostate is prone to infection and enlargement later in life, constricting the urethra so urinating becomes slow and painful.[67]

Prostatic secretions vary among species. They are generally composed of simple sugars and are often slightly alkaline.[68]

Skene’s gland[edit]

Because the Skene’s gland and the male prostate act similarly by secreting prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which is an ejaculate protein produced in males, and of prostate-specific acid phosphatase, the Skene’s gland is sometimes referred to as the «female prostate».[69][70] Although it is homologous to the male prostate (developed from the same embryological tissues),[71][72] various aspects of its development in relation to the male prostate are widely unknown and a matter of research.[73]

See also[edit]

- Ejaculatory duct

- Seminal vesicles

- Prostate evolution in monotreme mammals

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Vásquez, Bélgica (2014-03-01). «Morphological Characteristics of Prostate in Mammals». International Journal of Medical and Surgical Sciences. 1 (1): 63–72. doi:10.32457/ijmss.2014.010. ISSN 0719-532X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Young, Barbara; O’Dowd, Geraldine; Woodford, Phillip (2013). Wheater’s functional histology: a text and colour atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 347–8. ISBN 9780702047473.

- ^ Leissner KH, Tisell LE (1979). «The weight of the human prostate». Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 13 (2): 137–42. doi:10.3109/00365597909181168. PMID 90380.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Standring, Susan, ed. (2016). «Prostate». Gray’s anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia. pp. 1266–1270. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goddard, Jonathan Charles (January 2019). «The history of the prostate, part one: say what you see». Trends in Urology & Men’s Health. 10 (1): 28–30. doi:10.1002/tre.676.

- ^ a b «Basic Principles: Prostate Anatomy» Archived 2010-10-15 at the Wayback Machine. Urology Match. Www.urologymatch.com. Web. 14 June 2010.

- ^ a b «Prostate Cancer Information from the Foundation of the Prostate Gland.» Prostate Cancer Treatment Guide. Web. 14 June 2010.

- ^ Cohen RJ, Shannon BA, Phillips M, Moorin RE, Wheeler TM, Garrett KL (2008). «Central zone carcinoma of the prostate gland: a distinct tumor type with poor prognostic features». The Journal of Urology. 179 (5): 1762–7, discussion 1767. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.017. PMID 18343454.

- ^ a b Michael Schünke, Erik Schulte, Udo Schumacher: PROMETHEUS Innere Organe. LernAtlas Anatomie, vol 2: Innere Organe, Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart/Germany 2012, ISBN 9783131395337, p. 298, PDF.

- ^ «Prostate Gland Development». ana.ed.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2003-04-30. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- ^ «Prostate». webpath.med.utah.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-17.

- ^ «The human proteome in prostate – The Human Protein Atlas». www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- ^ Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). «Tissue-based map of the human proteome». Science. 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- ^ O’Hurley, Gillian; Busch, Christer; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn M.; Stadler, Charlotte; Tolf, Anna; Lundberg, Emma; Schwenk, Jochen M.; Jirström, Karin (2015-08-03). «Analysis of the Human Prostate-Specific Proteome Defined by Transcriptomics and Antibody-Based Profiling Identifies TMEM79 and ACOXL as Two Putative, Diagnostic Markers in Prostate Cancer». PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0133449. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1033449O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133449. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4523174. PMID 26237329.

- ^ Kong, HY; Byun, J (January 2013). «Emerging roles of human prostatic Acid phosphatase». Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 21 (1): 10–20. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2012.095. PMC 3762301. PMID 24009853.

- ^ a b Sadley, TW (2019). «Bladder and urethra». Langman’s medical embryology (14th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 263–66. ISBN 9781496383907.

- ^ a b c Sadley, TW (2019). Langman’s medical embryology (14th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 265–6. ISBN 9781496383907.

- ^ Moore, Keith L.; Persaud, T. V. N.; Torchia, Mark G. (2008). Before We are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects (7th ed.). ISBN 978-1-4160-3705-7.

- ^ a b c d e Barrett, Kim E. (2019). Ganong’s review of medical physiology. Barman, Susan M.,, Brooks, Heddwen L.,, Yuan, Jason X.-J. (26th ed.). New York. pp. 411, 415. ISBN 9781260122404. OCLC 1076268769.

- ^ Rosenthal, Martha (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. pp. 133–135. ISBN 978-0618755714. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Komisaruk, Barry R.; Whipple, Beverly; Nasserzadeh, Sara & Beyer-Flores, Carlos (2009). The Orgasm Answer Guide. JHU Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8018-9396-4. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ Levin, R. J. (2018). «Prostate-induced orgasms: A concise review illustrated with a highly relevant case study». Clinical Anatomy. 31 (1): 81–85. doi:10.1002/ca.23006. PMID 29265651.

- ^ Hocaoglu Y, Roosen A, Herrmann K, Tritschler S, Stief C, Bauer RM (2012). «Real-time magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): anatomical changes during physiological voiding in men». BJU Int. 109 (2): 234–9. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10255.x. PMID 21736694.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hocaoglu Y, Herrmann K, Walther S, Hennenberg M, Gratzke C, Bauer R; et al. (2013). «Contraction of the anterior prostate is required for the initiation of micturition». BJU Int. 111 (7): 1117–23. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11698.x. PMID 23356864.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lebdai S, Chevrot A, Doizi S, Pradere B, Delongchamps NB, Benchikh A; et al. (2019). «Do patients have to choose between ejaculation and miction? A systematic review about ejaculation preservation technics for benign prostatic obstruction surgical treatment» (PDF). World J Urol. 37 (2): 299–308. doi:10.1007/s00345-018-2368-6. PMID 29967947. S2CID 49556196. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-11. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Davidson’s 2018, pp. 437–9.

- ^ a b Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan CA (2006). «Sexual dysfunction in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: improvement after trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training». J. Urol. 176 (4 Pt 1): 1534–8, discussion 1538–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.383.7495. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.010. PMID 16952676.

- ^ «Physical Therapy Treatment for Prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome». 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ^ Christensen, TL; Andriole, GL (February 2009). «Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Current Treatment Strategies». Consultant. 49 (2).

- ^ Dineen MK, Shore ND, Lumerman JH, Saslawsky MJ, Corica AP (2008). «Use of a Temporary Prostatic Stent After Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy Reduced Voiding Symptoms and Bother Without Exacerbating Irritative Symptoms». J. Urol. 71 (5): 873–877. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.015. PMID 18374395.

- ^ Rawla P (April 2019). «Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer». World J Oncol (Review). 10 (2): 63–89. doi:10.14740/wjon1191. PMC 6497009. PMID 31068988.

- ^ Sandhu, Gurdarshan S.; Andriole, Gerald L. (September 2012). «Overdiagnosis of Prostate Cancer». Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Monographs. 2012 (45): 146–151. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs031. ISSN 1052-6773. PMC 3540879. PMID 23271765.

- ^ «What is Brachytherapy?». American Brachytherapy Society. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m «Surgery for Prostate Cancer». www.cancer.org. The American Cancer Society medical and editorial content team. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b «Surgery to remove your prostate gland | Prostate cancer | Cancer Research UK». www.cancerresearchuk.org. Cancer Research UK. 18 Jun 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Ghabili, Kamyar; Tosoian, Jeffrey J.; Schaeffer, Edward M.; Pavlovich, Christian P.; Golzari, Samad E.J.; Khajir, Ghazal; Andreas, Darian; Benzon, Benjamin; Vuica-Ross, Milena; Ross, Ashley E. (November 2016). «The History of Prostate Cancer From Antiquity: Review of Paleopathological Studies». Urology. 97: 8–12. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2016.08.032. PMID 27591810.

- ^ a b c d e f Josef Marx, Franz; Karenberg, Axel (1 February 2009). «History of the Term Prostate». The Prostate. 69 (2): 208–213. doi:10.1002/pros.20871. PMID 18942121. S2CID 44922919.

- ^ a b c Young, Robert H; Eble, John N (January 2019). «The history of urologic pathology: an overview». Histopathology. 74 (1): 184–212. doi:10.1111/his.13753. PMID 30565309. S2CID 56476748.

- ^ Myers, Robert P (2000). «Structure of the adult prostate from a clinician’s standpoint». Clinical Anatomy. 13 (3): 214–5. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(2000)13:3<214::AID-CA10>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 10797630. S2CID 33861863.

- ^ Adams J (1853). «The case of scirrhous of the prostate gland with corresponding affliction of the lymphatic glands in the lumbar region and in the pelvis». Lancet. 1 (1547): 393–94. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)68759-8.

- ^ Ghabili K, Tosoian JJ, Schaeffer EM, Pavlovich CP, Golzari SE, Khajir G, Andreas D, Benzon B, Vuica-Ross M, Ross AE (November 2016). «The History of Prostate Cancer From Antiquity: Review of Paleopathological Studies». Urology. 97: 8–12. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2016.08.032. PMID 27591810.

- ^ a b c Nahon, I; Waddington, G; Dorey, G; Adams, R (2011). «The history of urologic surgery: from reeds to robotics». Urologic Nursing. 31 (3): 173–80. doi:10.7257/1053-816X.2011.31.3.173. PMID 21805756.

- ^ Lytton B (June 2001). «Prostate cancer: a brief history and the discovery of hormonal ablation treatment». The Journal of Urology. 165 (6 Pt 1): 1859–62. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66228-3. PMID 11371867.

- ^ Samuel David Gross (1851). A Practical Treatise On the Diseases and Injuries of the Urinary Bladder, the Prostate Gland, and the Urethra. Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea.

«The idea of extirpating the entire gland is, indeed, too absurd to be seriously entertained… Excision of the middle lobe would be far less objectionable»