For the Turkish town and district, see Taşkent.

|

Tashkent Тошкент Toshkent |

|

|---|---|

|

Capital city |

|

|

Clockwise from top: Skyline of Tashkent, Kukeldash Madrasa, Cathedral of the Dormition of the Mother of God, Supreme Assembly building, Amir Timur Museum, Humo Ice Dome, Hilton Tashkent City, Tashkent at night. |

|

|

Flag Seal |

|

| Nickname:

Tash (A rock) |

|

| Motto(s):

Kuch Adolatdadir! |

|

Location of Tashkent in Uzbekistan |

|

|

Tashkent Tashkent Tashkent |

|

| Coordinates: 41°18′40″N 69°16′47″E / 41.31111°N 69.27972°ECoordinates: 41°18′40″N 69°16′47″E / 41.31111°N 69.27972°E | |

| Country | |

| Settled | 5th to 3rd centuries BC |

| Divisions | 12 districts |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Administration |

| • Hakim (Mayor) | Jahongir Ortiqxo’jayev |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 334.8 km2 (129.3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 455 m (1,493 ft) |

| Population

(1 July 2022)[1] |

|

| • Capital city | 2,909,466 |

| • Rank | 1st in Uzbekistan |

| • Metro | over 6 million |

| Time zone | UTC+5 ( ) |

| Area code | 71 |

| Vehicle registration | 01 |

| HDI (2019) | 0.809[2] very high |

| International Airports | Islam Karimov Tashkent International Airport |

| Rapid transit system | Tashkent Metro |

| Website | tashkent.uz |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Official name | Western Tien-Shan Mountain |

| Criteria | Natural: |

| Reference | 1490 |

| Inscription | 2016 (40th Session) |

| Area | 528,177.6 ha (1,305,155 acres) |

Tashkent (, Uzbek: Toshkent, Тошкент / تاشکند, , from Russian: Ташкент) or Toshkent (; IPA: [tɒʃˈkent]), historically known as Chach, is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of 2,909,500 (2022).[1] It is located in northeastern Uzbekistan, near the border with Kazakhstan. Tashkent comes from the Turkic tash and kent, literally translated as «Stone City» or «City of Stones».

Before Islamic influence started in the mid-8th century AD, Tashkent was influenced by the Sogdian and Turkic cultures. After Genghis Khan destroyed it in 1219, it was rebuilt and profited from the Silk Road. From the 18th to the 19th century, the city became an independent city-state, before being re-conquered by the Khanate of Kokand. In 1865, Tashkent fell to the Russian Empire; it became the capital of Russian Turkestan. In Soviet times, it witnessed major growth and demographic changes due to forced deportations from throughout the Soviet Union. Much of Tashkent was destroyed in the 1966 Tashkent earthquake, but it was rebuilt as a model Soviet city. It was the fourth-largest city in the Soviet Union at the time, after Moscow, Leningrad and Kyiv.[3]

Today, as the capital of an independent Uzbekistan, Tashkent retains a multiethnic population, with ethnic Uzbeks as the majority. In 2009, it celebrated its 2,200 years of written history.[4]

History[edit]

Etymology[edit]

During its long history, Tashkent has had various changes in names and political and religious affiliations. Abu Rayhan Biruni wrote that the city’s name Tashkent comes from the Turkic tash and kent, literally translated as «Stone City» or «City of Stones».[5] Ilya Gershevitch (1974:55, 72) (apud Livshits, 2007:179) traces the city’s old name Chach back to Old Iranian *čāiča- «area of water, lake» (cf. Lake Čaēčista mentioned in the Avesta) (whence Middle Chinese transcription *źiäk > standard Chinese Shí with Chinese character 石 for «stone»[6][7]), and *Čačkand ~ Čačkanθ was the basis for Turkic adaption Tashkent, popularly etymologized as «stone city».[8]

Early history[edit]

Tashkent was first settled some time between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC by ancient people as an oasis on the Chirchik River, near the foothills of the West Tian Shan Mountains. In ancient times, this area contained Beitian, probably the summer «capital» of the Kangju confederacy.[9] Some scholars believe that a «Stone Tower» mentioned by Ptolemy in his famous treatise Geography, and by other early accounts of travel on the old Silk Road, referred to this settlement (due to its etymology). This tower is said to have marked the midway point between Europe and China. Other scholars, however, disagree with this identification, though it remains one of four most probable sites for the Stone Tower.[10][11]

History as Chach[edit]

Coinage of Chach circa 625-725 CE

In pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, the town and the province were known as Chach. The Shahnameh of Ferdowsi also refers to the city as Chach.

The principality of Chach had a square citadel built around the 5th to 3rd centuries BC, some 8 km (5.0 mi) south of the Syr Darya River. By the 7th century AD, Chach had more than 30 towns and a network of over 50 canals, forming a trade center between the Sogdians and Turkic nomads. The Buddhist monk Xuanzang (602/603? – 664 AD), who travelled from China to India through Central Asia, mentioned the name of the city as Zhěshí (赭時). The Chinese chronicles History of Northern Dynasties, Book of Sui, and Old Book of Tang mention a possession called Shí 石 («stone») or Zhěshí 赭時 with a capital of the same name since the fifth century AD.[14]

In 558–603, Chach was part of the Turkic Khaganate. At the beginning of the 7th century, the Turkic Kaganate, as a result of internecine wars and wars with its neighbors, disintegrated into the Western and Eastern Kaganates. The Western Turkic ruler Tong Yabghu Qaghan (618-630) set up his headquarters in the Ming-bulak area to the north of Chach. Here he received embassies from the emperors of the Tang Empire and Byzantium.[15] In 626, the Indian preacher Prabhakaramitra arrived with ten companions to the Khagan. In 628, a Buddhist Chinese monk Xuanzang arrived in Ming Bulak.

The Turkic rulers of Chach minted their coins with the inscription on the obverse side of the «lord of the Khakan money» (mid-8th century); with an inscription in the ruler Turk (VII century), in Nudjket in the middle of the VIII century, coins were issued with the obverse inscription “Nanchu (Banchu) Ertegin sovereign».[16]

Islamic Caliphate[edit]

Tashkent was conquered by the Arabs at the beginning of the 8th century.[17]

According to the descriptions of the authors of the 10th century, Shash was structurally divided into a citadel, an inner city (madina) and two suburbs — an inner (rabad-dahil) and an outer (rabad-harij). The citadel, surrounded by a special wall with two gates, contained the ruler’s palace and the prison.[18]

Post Caliphate rule[edit]

Under the Samanid Empire, whose founder Ismail Samani was a descendant of Persian Zoroastrian convert to Islam, the city came to be known as Binkath. However, the Arabs retained the old name of Chach for the surrounding region, pronouncing it ash-Shāsh (الشاش) instead. Kand, qand, kent, kad, kath, kud—all meaning a city—are derived from the Persian/Sogdian کنده (kanda), meaning a town or a city. They are found in city names such as Samarkand, Yarkand, Panjakent, Khujand etc.).

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Ali ash-Shashi, known as al-Kaffal ash-Shashi (904-975), was born in Tashkent — an Islamic theologian, scholar, jurist of the Shafi’i madhhab, hadith scholar and linguist.[citation needed]

After the 11th century, the name evolved from Chachkand/Chashkand to Tashkand. The modern spelling of «Tashkent» reflects Russian orthography and 20th-century Soviet influence.

At the end of the 10th century, Tashkent became part of the possessions of the Turkic state of the Karakhanids. In 998/99 the Tashkent oasis went to the Karakhanid Ahmad ibn Ali, who ruled the north-eastern regions of Mavarannahr. In 1177/78, a separate khanate was formed in the Tashkent oasis. Its center was Banakat, where dirhams Mu’izz ad-dunya wa-d-din Qilich-khan were minted, in 1195-1197 — Jalal ad-dunya wa-d-din Tafgach-khakan, in 1197-1206 — ‘Imad ad-dunya va-d-din Ulug Egdish Chagry-khan.[19]

Mongol conquest[edit]

The city was destroyed by Genghis Khan in 1219 and lost much of its population as a result of the Mongols’ destruction of the Khwarezmid Empire in 1220.

Timurid period[edit]

Under the Timurid and subsequent Shaybanid dynasties, the city’s population and culture gradually revived as a prominent strategic center of scholarship, commerce and trade along the Silk Road.

During the reign of Amir Timur (1336-1405), Tashkent was restored and in the 14th-15th centuries Tashkent was part of Timur’s empire. For Timur, Tashkent was considered a strategic city. In 1391 Timur set out in the spring from Tashkent to Desht-i-Kipchak to fight the Khan of the Golden Horde Tokhtamysh Khan. Timur returned from this victorious campaign through Tashkent.[20]

The most famous saint Sufi of Tashkent was Sheikh Khovendi at-Takhur (13th to the first half of the 14th century). According to legend, Amir Timur, who was treating his wounded leg in Tashkent with the healing water of the Zem-Zem spring, ordered to build a mausoleum for the saint. By order of Timur, the Zangiata mausoleum was built.

Uzbek Shaybanid’s dynasty period[edit]

In the 16th century, Tashkent was ruled by the Shaybanid dynasty.[21][22]

Barak khan madrasa, Shaybanids, 16th century

Shaybanid Suyunchkhoja Khan was an enlightened Uzbek ruler; following the traditions of his ancestors Mirzo Ulugbek and Abul Khair Khan, he gathered famous scientists, writers and poets at his court, among them: Vasifi, Abdullah Nasrullahi, Masud bin Osmani Kuhistani. Since 1518 Vasifi was the educator of the son of Suyunchhoja Khan Keldi Muhammad, with whom, after the death of his father in 1525, he moved to Tashkent. After the death of his former pupil, he became the educator of his son, Abu-l-Muzaffar Hasan-Sultan.[23]

Later the city was subordinated to Shaybanid Abdullah Khan II (the ruler actually from 1557, officially in 1583–1598), who issued his coins here[24]

From 1598 to 1604 Tashkent was ruled by the Shaybanid Keldi Muhammad, who issued silver and copper coins on his behalf.[25]

Kazakh ruled period[edit]

In 1598, Kazakh Taukeel Khan was at war with the Khanate of Bukhara. The Bukhara troops sent against him were defeated by Kazakhs in the battle between Tashkent and Samarkand. During the reign of Yesim-Khan,[26] a peace treaty was concluded between Bukhara and Kazakhs, according to which Kazakhs abandoned Samarkand, but left behind Tashkent, Turkestan and a number of Syr Darya cities.

Yesim-Khan ruled the Kazakh Khanate from 1598 to 1628, his main merit was that he managed to unite the Kazakh khanate.

The city was part of Kazakh Khanate between 1598-1723.[27]

Tashkent state[edit]

In 1784, Yunus Khoja, the ruler of the dakha (district) Shayhantahur, united the entire city under his rule and created an independent Tashkent state (1784-1807), which by the beginning of the 19th century seized vast lands.[28]

Kokand Khanate[edit]

In 1809, Tashkent was annexed to the Khanate of Kokand.[29] At the time, Tashkent had a population of around 100,000 and was considered the richest city in Central Asia.

Under the Kokand domination, Tashkent was surrounded by a moat and an adobe battlement (about 20 kilometers long) with 12 gates.[30]

It prospered greatly through trade with Russia but chafed under Kokand’s high taxes. The Tashkent clergy also favored the clergy of Bukhara over that of Kokand. However, before the Emir of Bukhara could capitalize on this discontent, the Russian army arrived.

Colonial period[edit]

In May 1865, Mikhail Grigorevich Chernyayev (Cherniaev), acting against the direct orders of the Tsar and outnumbered at least 15–1, staged a daring night attack against a city with a wall 25 km (16 mi) long with 11 gates and 30,000 defenders. While a small contingent staged a diversionary attack, the main force penetrated the walls, led by a Russian Orthodox priest. Although the defense was stiff, the Russians captured the city after two days of heavy fighting and the loss of only 25 dead as opposed to several thousand of the defenders (including Alimqul, the ruler of the Kokand Khanate). Chernyayev, dubbed the «Lion of Tashkent» by city elders, staged a hearts-and-minds campaign to win the population over. He abolished taxes for a year, rode unarmed through the streets and bazaars meeting common people, and appointed himself «Military Governor of Tashkent», recommending to Tsar Alexander II that the city become an independent khanate under Russian protection.

Coats of arms of Tashkent, 1909

The Tsar liberally rewarded Chernyayev and his men with medals and bonuses, but regarded the impulsive general as a loose cannon, and soon replaced him with General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman. Far from being granted independence, Tashkent became the capital of the new territory of Russian Turkistan, with Kaufman as first Governor-General. A cantonment and Russian settlement were built across the Ankhor Canal from the old city, and Russian settlers and merchants poured in. Tashkent was a center of espionage in the Great Game rivalry between Russia and the United Kingdom over Central Asia. The Turkestan Military District was established as part of the military reforms of 1874. The Trans-Caspian Railway arrived in 1889, and the railway workers who built it settled in Tashkent as well, bringing with them the seeds of Bolshevik Revolution.

Effect of the Russian Revolution[edit]

With the fall of the Russian Empire, the Russian Provisional Government removed all civil restrictions based on religion and nationality, contributing to local enthusiasm for the February Revolution. The Tashkent Soviet of Soldiers’ and Workers’ Deputies was soon set up, but primarily represented Russian residents, who made up about a fifth of the Tashkent population. Muslim leaders quickly set up the Tashkent Muslim Council (Tashkand Shura-yi-Islamiya) based in the old city. On 10 March 1917, there was a parade with Russian workers marching with red flags, Russian soldiers singing La Marseillaise and thousands of local Central Asians. Following various speeches, Governor-General Aleksey Kuropatkin closed the events with words «Long Live a great free Russia».[31]

The First Turkestan Muslim Conference was held in Tashkent 16–20 April 1917. Like the Muslim Council, it was dominated by the Jadid, Muslim reformers. A more conservative faction emerged in Tashkent centered around the Ulema. This faction proved more successful during the local elections of July 1917. They formed an alliance with Russian conservatives, while the Soviet became more radical. The Soviet attempt to seize power in September 1917 proved unsuccessful.[32]

In April 1918, Tashkent became the capital of the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Turkestan ASSR). The new regime was threatened by White forces, basmachi; revolts from within, and purges ordered from Moscow.

Soviet period[edit]

The Courage Monument in Tashkent on a 1979 Soviet stamp

The city began to industrialize in the 1920s and 1930s.

Violating the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. The government worked to relocate factories from western Russia and Ukraine to Tashkent to preserve the Soviet industrial capacity. This led to great increase in industry during World War II.

It also evacuated most of the German communist emigres to Tashkent.[33] The Russian population increased dramatically; evacuees from the war zones increased the total population of Tashkent to well over a million. Russians and Ukrainians eventually comprised more than half of the total residents of Tashkent.[34] Many of the former refugees stayed in Tashkent to live after the war, rather than return to former homes.

During the postwar period, the Soviet Union established numerous scientific and engineering facilities in Tashkent.

On 10 January 1966, then Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and Pakistan President Ayub Khan signed a pact in Tashkent with Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin as the mediator to resolve the terms of peace after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965. On the next day, Shastri died suddenly, reportedly due to a heart attack. It is widely speculated that Shastri was killed by poisoning the water he drank.[citation needed]

Much of Tashkent’s old city was destroyed by a powerful earthquake on 26 April 1966. More than 300,000 residents were left homeless, and some 78,000 poorly engineered homes were destroyed,[35] mainly in the densely populated areas of the old city where traditional adobe housing predominated.[36] The Soviet republics, and some other countries, such as Finland, sent «battalions of fraternal peoples» and urban planners to help rebuild devastated Tashkent.

Tashkent was rebuilt as a model Soviet city with wide streets planted with shade trees, parks, immense plazas for parades, fountains, monuments, and acres of apartment blocks. The Tashkent Metro was also built during this time. About 100,000 new homes were built by 1970,[35] but the builders occupied many, rather than the homeless residents of Tashkent.[citation needed] Further development in the following years increased the size of the city with major new developments in the Chilonzor area, north-east and south-east of the city.[35]

At the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Tashkent was the fourth-largest city in the USSR and a center of learning in the fields of science and engineering.

Due to the 1966 earthquake and the Soviet redevelopment, little architectural heritage has survived of Tashkent’s ancient history. Few structures mark its significance as a trading point on the historic Silk Road.

Capital of Uzbekistan[edit]

Tashkent is the capital of and the most cosmopolitan city in Uzbekistan. It was noted for its tree-lined streets, numerous fountains, and pleasant parks, at least until the tree-cutting campaigns initiated in 2009 by the local government.[37]

Since 1991, the city has changed economically, culturally, and architecturally. New development has superseded or replaced icons of the Soviet era. The largest statue ever erected for Lenin was replaced with a globe, featuring a geographic map of Uzbekistan. Buildings from the Soviet era have been replaced with new modern buildings. The «Downtown Tashkent» district includes the 22-story NBU Bank building, international hotels, the International Business Center, and the Plaza Building.

Japanese Gardens in Tashkent

The Tashkent Business district is a special district, established for the development of small, medium and large businesses in Uzbekistan. In 2018, was started to build a Tashkent city (new Downtown) which would include a new business district with skyscrapers of local and foreign companies, world hotels such as Hilton Tashkent Hotel, apartments, biggest malls, shops and other entertainments. The construction of the International Business Center is planned to be completed by the end of 2021.[38] Fitch assigns “BB-” rating to Tashkent city, “Stable” forecast.[39]

In 2007, Tashkent was named a «cultural capital of the Islamic world» by Moscow News, as the city has numerous historic mosques and significant Islamic sites, including the Islamic University.[40] Tashkent holds the Samarkand Kufic Quran, one of the earliest written copies of the Quran, which has been located in the city since 1924.[41]

Tashkent is the most visited city in the country,[42] and has greatly benefited from increasing tourism as a result of reforms under president Shavkat Mirziyoyev and opening up by abolishing visas for visitors from the European Union and other developing countries or making visas easier for foreigners.[43]

Tashkent over the years[edit]

- Development of Tashkent

-

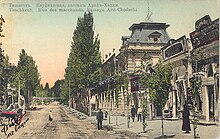

c. 1865

-

1913

-

1940

-

1965

-

1981

-

2000

The city and the origin of television[edit]

The first demonstration of a fully electronic TV set to the public was made in Tashkent in summer 1928 by Boris Grabovsky and his team. In his method that had been patented in Saratov in 1925, Boris Grabovsky proposed a new principle of TV imaging based on the vertical and horizontal electron beam sweeping under high voltage. Nowadays this principle of the TV imaging is used practically in all modern cathode-ray tubes. Historian and ethnographer Boris Golender (Борис Голендер in Russian), in a video lecture, described this event.[44] This date of demonstration of the fully electronic TV set is the earliest known so far. Despite this fact, most modern historians disputably consider Vladimir Zworykin and Philo Farnsworth[45] as inventors of the first fully electronic TV set. In 1964, the contribution made to the development of early television by Grabovsky was officially acknowledged by the Uzbek government and he was awarded the prestigious degree «Honorable Inventor of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic».

Geography and climate[edit]

Tashkent and vicinity, satellite image Landsat 5, 2010-06-30

| Tashkent | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Geography[edit]

Tashkent is situated in a well-watered plain on the road between Samarkand, Uzbekistan’s second city, and Shymkent across the border. Tashkent is just 13 km from two border crossings into Kazakhstan.

Closest geographic cities with populations of over 1 million are: Shymkent (Kazakhstan), Dushanbe (Tajikistan), Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan), Kashgar (China), Almaty (Kazakhstan), Kabul (Afghanistan) and Peshawar (Pakistan).

Tashkent sits at the confluence of the Chirchiq River and several of its tributaries and is built on deep alluvial deposits up to 15 m (49 ft). The city is located in an active tectonic area suffering large numbers of tremors and some earthquakes.

The local time in Tashkent is UTC/GMT +5 hours.

Climate[edit]

Tashkent features a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa)[47] bordering a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dsa).[47] As a result, Tashkent experiences cold and often snowy winters not typically associated with most Mediterranean climates and long, hot and dry summers. Most precipitation occurs during winter, which frequently falls as snow. The city experiences two peaks of precipitation in the early winter and spring. The slightly unusual precipitation pattern is partially due to its 500 m (1,600 ft) altitude. Summers are long in Tashkent, usually lasting from May to September. Tashkent can be extremely hot during the months of July and August. The city also sees very little precipitation during the summer, particularly from June through September.[48][49]

| Climate data for Tashkent (1981–2010, extremes 1881–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

27.0 (80.6) |

32.5 (90.5) |

36.4 (97.5) |

39.9 (103.8) |

45.0 (113.0) |

44.6 (112.3) |

43.1 (109.6) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.5 (99.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

27.3 (81.1) |

44.6 (112.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

35.6 (96.1) |

34.7 (94.5) |

29.3 (84.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

3.9 (39.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

20.5 (68.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

8.5 (47.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.5 (29.3) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.7 (56.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

0.0 (32.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28 (−18) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.7 (42.3) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−22.1 (−7.8) |

−29.5 (−21.1) |

−29.5 (−21.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53.3 (2.10) |

63.8 (2.51) |

70.2 (2.76) |

62.3 (2.45) |

41.2 (1.62) |

14.3 (0.56) |

4.5 (0.18) |

1.3 (0.05) |

6.0 (0.24) |

24.7 (0.97) |

43.9 (1.73) |

58.9 (2.32) |

444.4 (17.50) |

| Average precipitation days | 14 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 110 |

| Average snowy days | 9 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 27 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73 | 68 | 61 | 60 | 53 | 40 | 39 | 42 | 45 | 57 | 66 | 73 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 117.3 | 125.3 | 165.1 | 216.8 | 303.4 | 361.8 | 383.7 | 365.8 | 300.9 | 224.8 | 149.5 | 105.9 | 2,820.3 |

| Source 1: Centre of Hydrometeorological Service of Uzbekistan[50] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Pogoda.ru.net (mean temperatures/humidity/snow days 1981–2010, record low and record high temperatures),[51] NOAA (mean monthly sunshine hours, 1961–1990)[52] OGIMET[53] |

Demographics[edit]

Bread vendor in a market street of Tashkent

In 1983, the population of Tashkent amounted to 1,902,000 people living in a municipal area of 256 km2 (99 sq mi). By 1991, (Dissolution of the Soviet Union) the number of permanent residents of the capital had grown to approximately 2,136,600. Tashkent was the fourth most populated city in the former USSR, after Moscow, Leningrad (St. Petersburg), and Kyiv. Nowadays, Tashkent remains the fourth most populous city in the CIS. The population of the city was 2,716,176 people in 2020.[54]

As of 2008, the demographic structure of Tashkent was as follows:[citation needed]

- 78.0% – Uzbeks

- 5% – Russians

- 4.5% – Tatars

- 2.2% – Koryo-saram (Koreans)

- 2.1% – Tajiks

- 1.2% – Uighurs

- 7.0% – other ethnic backgrounds[citation needed]

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Uzbekistan State Statistics Committee[55][56] and Demoscope.ru[57][58][59][60][61] |

Uzbek is the main spoken language as well as Russian for inter-ethnic communication. As with most of Uzbekistan, street signs and other things are often a mix of Latin and Cyrillic scripts.[62][63]

Districts[edit]

Panorama of Tashkent pictured 2010

Amir Timur Street pictured 2006

A downtown street pictured 2012

Since 2020, when the Yangihayot district was created,[64] Tashkent is divided into the following 12 districts (Uzbek: tumanlar):

| Nr | District | Population (2021)[1] |

Area (km2)[65][64] |

Density (area/km2) |

Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bektemir | 31,400 | 17.83 | 1,761 |

|

| 2 | Chilanzar | 260,700 | 29.94 | 8,707 |

|

| 3 | Yashnobod | 258,800 | 33.7 | 7,680 |

|

| 4 | Mirobod | 142,800 | 17.1 | 8,351 |

|

| 5 | Mirzo Ulugbek | 285,000 | 35.15 | 8,108 |

|

| 6 | Sergeli | 105,700 | 37.36 | 2,829 |

|

| 7 | Shayxontoxur | 348,300 | 29.7 | 11,727 |

|

| 8 | Olmazor | 377,100 | 34.5 | 10,930 |

|

| 9 | Uchtepa | 278,200 | 24 | 11,592 |

|

| 10 | Yakkasaray | 121,600 | 14.6 | 8,329 |

|

| 11 | Yunusabad | 352,000 | 40.6 | 8,670 |

|

| 12 | Yangihayot | 132,800 | 44.20 | 3,005 |

At the time of the Tsarist take over it had four districts (Uzbek daha):

- Beshyoghoch

- Kukcha

- Shaykhontokhur

- Sebzor

In 1940 it had the following districts (Russian район):

- Oktyabr

- Kirov

- Stalin

- Frunze

- Lenin

- Kuybishev

By 1981 they were reorganized into:[35]

- Bektemir

- Akmal-Ikramov (Uchtepa)

- Khamza (Yashnobod)

- Lenin (Mirobod)

- Kuybishev (Mirzo Ulugbek)

- Sergeli

- Oktober (Shaykhontokhur)

- Sobir Rakhimov (Olmazar)

- Chilanzar

- Frunze (Yakkasaray)

- Kirov (Yunusabad)

Main sights[edit]

Alisher Navoi Opera and Ballet Theatre

Due to the destruction of most of the ancient city during the 1917 revolution and, later, the 1966 earthquake, little remains of Tashkent’s traditional architectural heritage. Tashkent is, however, rich in museums and Soviet-era monuments. They include:

- Kukeldash Madrasah. Dating back to the reign of Abdullah Khan II (1557–1598) it is being restored by the provincial Religious Board of Mawarannahr Moslems. There is talk of making it into a museum, but it is currently being used as a madrassah.

- Chorsu Bazaar, located near the Kukeldash Madrassa. This huge open air bazaar is the center of the old town of Tashkent. Everything imaginable is for sale. It is one of the major tourist attractions of the city.

- Hazrati Imam Complex. It includes several mosques, shrine, and a library which contains a manuscript Qur’an in Kufic script, considered to be the oldest extant Qur’an in the world. Dating from 655 and stained with the blood of murdered caliph, Uthman, it was brought by Timur to Samarkand, seized by the Russians as a war trophy and taken to Saint Petersburg. It was returned to Uzbekistan in 1924.[66]

- Yunus Khan Mausoleum. It is a group of three 15th-century mausoleums, restored in the 19th century. The biggest is the grave of Yunus Khan, grandfather of Mughal Empire founder Babur.

- Palace of Prince Romanov. During the 19th century Grand Duke Nikolai Konstantinovich, a first cousin of Alexander III of Russia was banished to Tashkent for some shady deals involving the Russian Crown Jewels. His palace still survives in the centre of the city. Once a museum, it has been appropriated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Alisher Navoi Opera and Ballet Theatre, built by the same architect who designed Lenin’s Tomb in Moscow, Aleksey Shchusev, with Japanese prisoner of war labor in World War II. It hosts Russian ballet and opera.

- Fine Arts Museum of Uzbekistan. It contains a major collection of art from the pre-Russian period, including Sogdian murals, Buddhist statues and Zoroastrian art, along with a more modern collection of 19th and 20th century applied art, such as suzani embroidered hangings. Of more interest is the large collection of paintings «borrowed» from the Hermitage by Grand Duke Romanov to decorate his palace in exile in Tashkent, and never returned. Behind the museum is a small park, containing the neglected graves of the Bolsheviks who died in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and to Osipov’s treachery in 1919,[67] along with first Uzbekistani President Yuldosh Akhunbabayev.

- Museum of Applied Arts. Housed in a traditional house originally commissioned for a wealthy tsarist diplomat, the house itself is the main attraction, rather than its collection of 19th and 20th century applied arts.

- State Museum of History of Uzbekistan the largest museum in the city. It is housed in the ex-Lenin Museum.

- Amir Timur Museum, housed in a building with brilliant blue dome and ornate interior. It houses exhibits of Timur and of President Islam Karimov. To adjacent south of the museum is Amir Timur Square where there is a statue of Timur on horseback, surrounded by some of the nicest gardens and fountains in the city.

- Navoi Literary Museum, commemorating Uzbekistan’s adopted literary hero, Alisher Navoi, with replica manuscripts, Islamic calligraphy and 15th century miniature paintings.

- The Tashkent Metro is known for extravagant design and architecture in the buildings. Taking photos in the system was banned until 2018.[68]

The Russian Orthodox church in Amir Temur Square, built in 1898, was demolished in 2009. The building had not been allowed to be used for religious purposes since the 1920s due to the anti-religious campaign conducted across the former Soviet Union by the Bolshevik (communist) government in Moscow. During the Soviet period the building was used for different non-religious purposes; after independence it was a bank.

Tashkent also has a World War II memorial park and a Defender of Motherland monument.[69][70][71]

Education[edit]

Most important scientific institutions of Uzbekistan, such as the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, are located in Tashkent. There are several universities and institutions of higher education:

- TEAM University

- The Branch of the Russian State University of Oil and Gas (NRU) named after I.M. Gubkin

- Tashkent Automobile and Road Construction Institute

- Tashkent State Technical University

- Tashkent Institute of Architecture and Construction

- Tashkent Institute of Irrigation and Melioration

- International Business School Kelajak Ilmi

- Tashkent University of Information Technologies

- Westminster International University in Tashkent

- Turin Polytechnic University in Tashkent

- National University of Uzbekistan

- University of World Economy and Diplomacy

- Tashkent State Economic University

- Tashkent State Institute of Law

- Tashkent Financial Institute

- State Conservatory of Uzbekistan

- Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute

- Tashkent State Medicine Academy

- Tashkent State University of Oriental Studies

- Tashkent Islamic University

- Management Development Institute of Singapore in Tashkent

- Tashkent Institute of Textile and Light Industry

- Tashkent Institute of Railway Transport Engineers

- National Institute of Arts and Design named after Kamaleddin Bekhzod

- Inha University Tashkent

- Uzbekistan State University of World Languages

- AKFA UNIVERSITY

Media[edit]

- Nine Uzbek language newspapers, four in English, and nine in Russian.

- Several television and cable television facilities, including Tashkent Tower, the second tallest structure in Central Asia.

- Moreover, there are digital broadcasting systems available in Tashkent which is unique in Central Asia.

Transportation[edit]

Inside a Tashkent Metro station

- Tashkent Metro

- Tashkent International Airport is the largest in the country, connecting the city to Asia, Europe and North American continents.

- Tashkent–Samarkand high-speed rail line

- Trolleybus system was closed down in 2010.

- Tram transport ended at 1 May 2016.

Entertainment and shopping[edit]

There are several shopping malls in Tashkent. These include Next, Samarqand Darvoza and Kontinent shopping malls.[72] Most of the malls, including Riviera and Compass mall, were built and are operated by the Tower Management Group.[73] This is part of the Orient Group of Companies.[74]

The capital’s most established theatre is the Alisher Navoi Theater, that has regular ballet and opera performances.[75] Ilkhom Theater, founded by Mark Weil in 1976, was the first independent theater in the Soviet Union. The theater still operates in Tashkent and is known for its historical reputation.[76]

Sport[edit]

Football is the most popular sport in Tashkent, with the most prominent football clubs being Pakhtakor Tashkent FK, FC Bunyodkor, and PFC Lokomotiv Tashkent, all three of which compete in the Uzbekistan Super League. Footballers Maksim Shatskikh, Peter Odemwingie and Vasilis Hatzipanagis were born in the city.

Humo Tashkent, a professional ice hockey team was established in 2019 with the aim of joining Kontinental Hockey League (KHL), a top level Eurasian league in future. Humo joined the second-tier Supreme Hockey League (VHL) for the 2019–20 season. Humo play their games at the Humo Ice Dome; both the team and arena derive their name from the mythical Huma bird.[77]

Humo Tashkent was a member of the reformed Uzbekistan Ice Hockey League which began play in February 2019.[78] Humo finished in first place at the end of the regular season.

Cyclist Djamolidine Abdoujaparov was born in the city, while tennis player Denis Istomin was raised there.

Akgul Amanmuradova and Iroda Tulyaganova are notable female tennis players from Tashkent.

Gymnasts Alina Kabaeva and Israeli Olympian Alexander Shatilov were also born in the city.

Former world champion and Israeli Olympic bronze medalist sprint canoer in the K-1 500 m event Michael Kolganov was also born in Tashkent.[79]

In Weightlifting, Uzbekistan won the heavyweight class in both the Rio.[80] and Tokyo [81]Olympic Games. Tashkent is hosting the 2021 Weightlifting World Championships.[82]

Notable people[edit]

- Behzod Abduraimov, Uzbek classical pianist

- Said Ahmad [uz], Uzbek novelist

- Ismoilkhuja Akhmedkhodjaev, Uzbek racing driver

- Turgun Alimatov, Uzbek classic music and shashmaqam player and composer

- Natasha Alam, Uzbekistani–American actress and model

- Abdulla Aripov, Uzbek politician and Prime Minister of Uzbekistan

- Lola Astanova, Russian-American pianist

- Sogdiana Fedorinskaya, Uzbekistani singer and actress

- Gʻafur Gʻulom, poet

- Olga Hritsenko, teacher, scientist, social worker; Honored Teacher of Ukraine

- Ravshan Irmatov, football referee

- Arthur Kaliyev, born in Tashkent raised in Staten Island, New York, American ice hockey player for the Los Angeles Kings of the NHL

- Rustam Kasimdzhanov, chess player, former FIDE World Champion

- Moshe Kaveh (born 1943), Israeli physicist and former President of Bar-Ilan University

- Vladimir Kozlov, Ukrainian-American professional wrestler

- Varvara Lepchenko, Uzbekistani-born American professional tennis player

- Olena Lytovchenko, writer

- Tohir Malik, novelist

- Boris Mavashev, Israeli seismologist

- Eson Kandov, singer and musician

- Abdulla Qodiriy, writer

- Mirjalol Qosimov, former player and head coach of the Uzbekistan national football team

- Igor Povalyayev, former Russian-Uzbekistani professional footballer

- Svetlana Radzivil, Uzbekistani high jumper

- Artur Rozyyev, former Russian professional football player

- Tursunoy Saidazimova, singer

- Shakhida Shaimardanova, composer

- Iroda Tulyaganova, former tennis player

- Alisher Usmanov, born in Chust, Uzbekistan, spent his childhood in Tashkent

- Milana Vayntrub, Uzbek-born American actress and comedian

- Rita Volk, Uzbekistani–American actress

- Hakim Karimovich Zaripov, circus performer

- Farrukh Zokirov, Uzbek and Soviet singer

- Zulfiya, writer and poet

- Sodiq Safoyev, first deputy chairperson of the Senate of Uzbekistan’s Parliament

- Ali Hamroyev, Uzbek actor, film director, screenwriter, and film producer

- Abid Sadykov, organic chemist, academician, and politician

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Tashkent is twinned with:[83]

Ankara, Turkey[84]

Ashgabat, Turkmenistan[85]

Astana, Kazakhstan[86]

Berlin, Germany

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Cairo, Egypt[87]

Dnipro, Ukraine

Kyiv, Ukraine

Moscow, Russia

Nagoya, Japan

Riga, Latvia

Seattle, United States[88]

Seoul, South Korea

Shanghai, China

Sverdlovsk, Ukraine

See also[edit]

- Gates of Tashkent

- Tashkent Declaration

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «Urban and rural population by district» (PDF) (in Uzbek). Tashkent City department of statistics.

- ^ «Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab». hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ Praying Through the 100 Gateway Cities of the 10/40 Window, ISBN 978-0-927-54580-8, p. 89.

- ^ «Юбилей Ташкента. Такое бывает только раз в 2200 лет». Фергана – международное агентство новостей. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Sachau, Edward C. Alberuni’s India: an Account of the Religion. Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India about AD 1030, vol. 1 London: KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRtJBNBR & CO. 1910. p.298.

- ^ Čāč at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Personal Names, Sogdian i. in Chinese sources at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Livshits, Vladimir (2007). «The Leader of the People of Chach in Sogdian Inscriptions» in Macuch, Maggi, & Sundermann (eds.) Iranian Languages and Texts from Iran and Turan. Ronald E. Emmerick Memorial Volume. p. 179

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. «The Consonantal System of Old Chinese,» Asia Major 9 (1963), p. 94.

- ^ Dean, Riaz (2022). The Stone Tower: Ptolemy, the Silk Road, and a 2,000-Year-Old Riddle. Delhi: Penguin Viking. pp. 134 (Map 4), 170. ISBN 978-0670093625.

- ^ Dean, Riaz (2015). «The Location of Ptolemy’s Stone Tower: the Case for Sulaiman-Too in Osh». The Silk Road. 13: 76.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Whitfield, Susan (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library. Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- ^ Bichurin, 1950. v. II

- ^ Golden, P.B. An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. Series: Turcologica. Wiesbaden: Otto-Harrassowitz. 1992

- ^ Baratova L. S. Drevnetyurkskiye monety Sredney Azii VI—IKH vv. (tipologiya, ikonografiya, istoricheskaya interpretatsiya). Avtoreferat diss. kand. ist. nauk. — T., 1995, s.12

- ^ O. G. Bol’shakov. Istoriya Khalifata, t. 4: apogey i padeniye. — Moskva: «Vostochnaya literatura» RAN, 2010

- ^ Filanovich, M.I. Tashkent (zarozhdeniye i razvitiye goroda i gorodskoy kul’tury). Tashkent, 1983, p.188

- ^ Kochnev B. D., Numizmaticheskaya istoriya Karakhanidskogo kaganata (991—1209 gg.). Moskva «Sofiya», 2006, p.157,234

- ^ Fasikh Akhmad ibn Dzhalal ad-Din Mukhammad al-Khavafi. Fasikhov svod. Tashkent: Fan. 1980, p.114

- ^ Dobromyslov A. I., Tashkent v proshlom i nastoyashchem. Tashkent, 1912, p.9

- ^ Istoriya Tashkenta. Tashkent: Fan, 1988, p.70

- ^ Yudin V. P. Materialy po istorii kazakhskikh khanstv XV-XVIII vekov. (Izvlecheniya iz persidskikh i tyurkskikh sochineniy). — Alma-Ata : Nauka, 1969, p.174.

- ^ Ye. A. Davidovich, Korpus zolotykh i serebryanykh monet Sheybanidov. XVI vek. M., 1992

- ^ Burnasheva R. Z., Nekotoryye svedeniya o chekanke mednykh monet v Tashkente v XVI—XIX vv. Izvestiya Natsional’noy akademii nauk Kazakhstana, № 1, 2007, p.153

- ^ «Yesim-Khan». www.researchgate.net.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia,Volume V, UNESCO Publishing, page 97,https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000130205/PDF/130205eng.pdf.multi

- ^ Istoriya Tashkenta (s drevneyshikh vremon do pobedy Fevral’skoy burzhuazno-demokraticheskoy revolyutsii) / Ziyayev KH. Z., Buryakov YU. V. Tashkent: «Fan», 1988

- ^ Planet, Lonely. «History in Tashkent, Uzbekistan».

- ^ Istoriya Tashkenta (s drevneyshikh vremyon do pobedy Fevralskoy burzhuazno-demokraticheskoy revolyutsii) / Ziyayev Kh. Z., Buryakov Y.F. Tashkent: «Fan», 1988

- ^ Jeff Sahadeo, Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent, Indiana University Press, 2007, p188

- ^ Rex A. Wade, The Russian Revolution, 1917, Cambridge University Press, 2005

- ^ Robert K. Shirer, «Johannes R. Becher 1891–1958» Archived 7 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopedia of German Literature, Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2000, by permission at Digital Commons, University of Nebraska, accessed 3 February 2013

- ^ Edward Allworth (1994), Central Asia, 130 Years of Russian Dominance: A Historical Overview Archived 30 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Duke University Press, p. 102. ISBN 0-8223-1521-1

- ^ a b c d Sadikov, A C; Akramob Z. M.; Bazarbaev, A.; Mirzlaev T.M.; Adilov S. R.; Baimukhamedov X. N.; et al. (1984). Geographical Atlas of Tashkent (Ташкент Географический Атлас) (in Russian) (2 ed.). Moscow. pp. 60, 64.

- ^ Nurtaev Bakhtiar (1998). «Damage for buildings of different type». Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ «Good bye the Tashkent Public Garden!». Ferghana.Ru. 23 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ https://www.fitchratings.com/research/ru/international-public-finance/fitch-prisvoilo-gorodu-tashkentu-rejting-bb-prognoz-stabil-nyj-17-06-2019 Archived 8 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine[bare URL]

- ^ «Moscow News – World – Tashkent Touts Islamic University». Mnweekly.ru. 21 June 2007. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ «Tashkent’s hidden Islamic relic». BBC. 5 January 2006. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ «Uzbekistan doubles the number of tourists in 2018». Brussels Express. 23 November 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ «Uzbekistan announces ambition to become major tourist destination». Euractiv. 19 November 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ «Видеолекторий «Ферганы»: Изобретение телевидения и Борис Грабовский». Фергана.Ру.

- ^ K. Krull, The boy who invented TV: The story of Philo Farnsworth, 2014

- ^

«World Weather Information Service – Tashkent». World Meteorological Organisation. Retrieved 16 August 2012. - ^ a b Updated Asian map of the Köppen climate classification system

- ^ Tashkent Travel. «Tashkent weather forecast». Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ Happy-Tellus.com. «Tashkent, Uzbekistan travel information». Helsinki, Finland: Infocenter International Ltd. Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^

«Average monthly data about air temperature and precipitation in 13 regional centers of the Republic of Uzbekistan over period from 1981 to 2010». Centre of Hydrometeorological Service of the Republic of Uzbekistan (Uzhydromet). Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019. - ^

«Weather and Climate-The Climate of Tashkent» (in Russian). Weather and Climate. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019. - ^

«Tashkent Climate Normals 1961–1990». National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 12 February 2017. - ^ «38457: Tashkent (Uzbekistan)». OGIMET. 16 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ «ТАШКЕНТ (город)». Dic.academic.ru. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ «Hududlar boʻyicha shahar va qishloq aholisi soni (2010–2021-yillar)» (in Uzbek). Uzbekistan State Statistics Committee. 16 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ^ «Постоянное среднее число населения» (in Russian). Uzbekistan State Statistics Committee. 27 September 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ «Демоскоп Weekly — Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей». www.demoscope.ru.

- ^ «Демоскоп Weekly — Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей». www.demoscope.ru.

- ^ «Демоскоп Weekly — Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей». www.demoscope.ru.

- ^ «Демоскоп Weekly — Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей». www.demoscope.ru.

- ^ «Демоскоп Weekly — Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей». www.demoscope.ru.

- ^ «Uzbekistan: A second coming for the Russian language?». eurasianet. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ «Uzbekistan: Dead Letter». Chalkboard. 23 July 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ a b «Deputies approved the creation of Yangihayot district of Tashkent» (in Russian). Gazeta.uz. 9 September 2020.

- ^ «Districts». City of Tashkent. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ MacWilliams, Ian (5 January 2006). «Tashkent’s hidden Islamic relic». BBC News. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ Smele, Jonathan D. (20 November 2015). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916–1926. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 58. ISBN 978-1442252806. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Inside Uzbekistan’s beautiful, rarely-seen metro. National Geographic. 2 October 2018.

- ^ uznews.net, Tashkent’s central park is history Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 25 November 2009

- ^ Army memorial dismantled in Tashkent Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 24 November 2009

- ^ Ferghana.ru, МИД России указал послу Узбекистана на обеспокоенность «Наших» Archived 25 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, 16 January 2010 (in Russian)

- ^ Usbekistan: Entlang der Seidenstraße nach Samarkand, Buchara und Chiwa ISBN 978-3-89794-390-2 p. 111

- ^ «В Ташкенте открылся новый ТРЦ Compass». uznews.uz (in Russian). Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ «Главная/EN». orientgroup.uz. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ «State Academic Bolshoi Theatre named after Alisher Navoi». gabt.uz. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ «Сайт театра «Ильхом»«. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ «Bird of Happiness – a symbol of the HC HUMO» (in Russian). 22 July 2019.

- ^ «Uzbekistan eyes to join International Ice Hockey Federation». 15 February 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ «Sports-reference.com». Sports-reference.com. 24 October 1974. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ «Results by Events Old BW».

- ^ «Results by Events».

- ^ «IWF World Championships». iwf.sport. 21 November 2021.

- ^ «Ну, здравствуй, брат! Города-побратимы Ташкента». vot.uz (in Russian). The Voice of Tashkent. 10 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ «Ankaranın Kardeş Şehirleri». ankara.bel.tr (in Turkish). Ankara. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ «Kostroma is looking for a twin city in Turkmenistan». orient.tm. Orient. 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ «Международный авторитет Астаны повышают города-побратимы». inform.kz (in Russian). KazInform. 6 July 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ «Brotherhood & Friendship Agreements». cairo.gov.eg. Cairo. Retrieved 15 November 2020.

- ^ Long, Priscilla (12 September 1988). «Seattle-Tashkent Peace Park in Uzbekistan is dedicated in Tashkent and at Seattle Center on September 12, 1988». HistoryLink.org. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

Museum of Fine Arts

Further reading[edit]

- Stronski, Paul, Tashkent: Forging a Soviet City, 1930–1966 (Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010).

- Jeff Sahadeo, Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent, 1865–1923 (Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press, 2010).

External links[edit]

ташкент

-

1

ташкент

Sokrat personal > ташкент

-

2

Ташкент

1) Colloquial: scorcher

2) Geography: Toshkent , Tashkent

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Ташкент

-

3

Ташкент

Русско-английский синонимический словарь > Ташкент

-

4

Ташкент (г.)

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Ташкент (г.)

-

5

Ташкент

Русско-английский географический словарь > Ташкент

-

6

Ташкент

Новый русско-английский словарь > Ташкент

-

7

Ташкент

Русско-английский словарь Wiktionary > Ташкент

-

8

Ташкент

Новый большой русско-английский словарь > Ташкент

-

9

Ташкент

Американизмы. Русско-английский словарь. > Ташкент

-

10

ташкент

Русско-английский большой базовый словарь > ташкент

-

11

(г.) Ташкент

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > (г.) Ташкент

-

12

П-537

НА ПРИМЕТЕ у кого быть, быть*,, иметься

PrepP

Invar

subj-complwith copula (

subj

: human, collect,

concr

, or count

abstr

)) a person (thing

etc

) has been noticed by

s.o.

, brought to the attention of

s.o. etc

, and

usu.

is the object of his ongoing interest, attention, plans

etc

: у Y-a есть на примете один (такой и т. п.) X — Y has an (a certain, one) X in mind

Y has his eye on an X (a certain X, one X (that…)etc

)

Y knows of an (oneetc

) X

there’s this one (a certain) X who(m) (that) Y has his eye on (who (that)…)(этот) X у Y-a давно на примете — Y has had an (his) eye on (this (that)) X for (quite) some time (for quite a while (now)

etc

)

Большой русско-английский фразеологический словарь > П-537

-

13

то и дело

every now and then; again and again; every moment

В ресторане играла радиола, то и дело прерывая её, дежурная объявляла посадку: Ташкент, Алма-Ата… (Д. Гранин, Иду на грозу) — Music was coming over the loudspeaker in the restaurant. Every now and then a voice would interrupt to announce the flight departures: Tashkent, Alma-Ata…

Он вышел на улицу и потихоньку стал прохаживаться до угла и обратно, то и дело оборачиваясь, чтоб не пропустить Наташу. (Ф. Кнорре, Шорох сухих листьев) — He went outside and began pacing to the corner and back, turning every moment to make sure of not missing Natasha.

В больничном дворе то и дело горланил одуревший от жары петух. (В. Шукшин, Нечаянный выстрел) — A heat-bemused cock crowed again and again in the hospital yard.

Русско-английский фразеологический словарь > то и дело

См. также в других словарях:

-

Ташкент — Ташкент … Словник лемківскої говірки

-

Ташкент — столица Узбекистана. По археологическим данным город основан в IV III тыс. до н. э., но в письменных источниках упоминается с IV V вв. н. э. под названиями Джадж, Чачкент, Шашкент, Бинкент. И только в XI в. в трудах среднеазиатских ученых Абу… … Географическая энциклопедия

-

Ташкент — Ташкент. Медресе Кукельдаш. ТАШКЕНТ, столица Узбекистана, областной центр, в предгорьях Западного Тянь Шаня. 2120 тыс. жителей. Железнодорожный узел. Метрополитен (1977). Машиностроение и металлообработка (сельскохозяйственные и текстильные… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

Ташкент — столица Узбекской ССР. Расположена в долине р. Чирчик. В период раннего средневековья город княжества Шаш (Чач) с тем же названием. В V VIII вв. на территории современного Ташкента возникли укреплённые поселения (городища Минг Урюк,… … Художественная энциклопедия

-

ТАШКЕНТ — ТАШКЕНТ, столица Узбекистана, областной центр, в предгорьях Западного Тянь Шаня. 2120 тыс. жителей. Железнодорожный узел. Метрополитен (1977). Машиностроение и металлообработка (сельскохозяйственные и текстильные машины, экскаваторы, самолеты,… … Современная энциклопедия

-

ТАШКЕНТ — столица (с 1930) Узбекистана, центр Ташкентской обл. Железнодорожный узел. 2113,3 тыс. жителей (1991; включая населенные пункты, подчиненные городской администрации, 2119,9 тыс. жителей). Ведущая отрасль промышленности машиностроение (ПО:… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Ташкент — I • Ташкент столица (с 1930) Узбекистана, центр Ташкентской области. Железнодорожный узел. 2121 тыс. жителей (1993). Ведущая отрасль промышленности машиностроение (ПО: «Узбексельмаш», «Узбектекстильмаш», авиационное и др.; заводы:… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

ташкент — ТАШКЕНТ, а, м. и в зн. сказ. Жара, зной, духота. назв. города, столицы Узбекистана; Возм. через уг. «ташкент» костер, печь, тепло … Словарь русского арго

-

Ташкент — столица и крупнейший город Узбекистана в предгорьях Западного Тянь Шаня, на реке Чирчик. Население свыше 2 млн. жителей.

Краткая… … Города мира -

ТАШКЕНТ — лидер эсминцев Черноморского флота (в строю с 1940). При обороне Одессы и Севастополя (1941 42) поддерживал огнем сухопутные войска, перевез большое количество войск и грузов. Погиб в июле 1942 в порту Новороссийска при налете вражеской авиации … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

ташкент — сущ., кол во синонимов: 7 • город (2765) • духота (18) • жара (23) • зной … Словарь синонимов

ташкент — перевод на английский

ташкент — tashkent

Москва, Ташкент, Бишкек.

Moscow, Tashkent and Pishpek.

Граф Вронский едет в Ташкент и желал бь проститься с нами.

Count Vronsky is leaving for Tashkent, and he would like to say goodbye to us.

Вронский — олицетворенная честь, и он уезжает в Ташкент…

Vronsky is the soul of honour, and he’s leaving for Tashkent…

в ташкент что ль в госпиталь, да?

Then they took him to the hospital To Tashkent I guess

Показать ещё примеры для «tashkent»…

Отправить комментарий

Текст комментария:

Устрою ее учиться.

В Ташкент. Мне помогут.

Хороший ты человек.

I’ll send her to a school, there.

There are some people willing to help in Tashkent.

You are a good man.

— Конечно.

Мы в Ташкенте жить будем?

Ты будешь жить и учиться в детском доме. Ташкент очень большой, красивый город.

— Of course.

Are we going to stay in Tanskhent?

You’re going to stay and study in the orphanage.

Сулман, скажи ты!

Москва, Ташкент, Бишкек.

Алтынай, посчитай сколько городов назвал Сулман.

You answer Shuvan.

Moscow, Tashkent and Pishpek.

Altynai, count how many cities Shuvan cited.

Аа, когда будете в Ташкенте?

Завтра к вечеру должны быть в Ташкенте.

— Можно мне спросить?

What time are you arriving in Tanskhent?

Tomorrom, towards the evening.

— May I ask something?

Или ты хочешь всю жизнь байские объедки подбирать?

Москва раз, Ташкент два, Бишкек три.

Молодец, Сулман.

Or you want to eat left-overs for the rest of your life?

Moscow-one, Tashkent-two, Pishpek-three.

Bravo, Shuvan.

— 16.

Аа, когда будете в Ташкенте?

Завтра к вечеру должны быть в Ташкенте.

— 16.

What time are you arriving in Tanskhent?

Tomorrom, towards the evening.

Мы в Ташкенте жить будем?

Ташкент очень большой, красивый город.

Там есть большие парки, сады, кино широкие улицы, магазины и высокие дома.

Are we going to stay in Tanskhent?

You’re going to stay and study in the orphanage.

Tanskhent is a very big and beautiful city. It has large parks, gardens and a cinema theatre… enormous roads and shops.

— Как его здоровье?

Собирается в Ташкент.

Исаия, ликуй!

— How is his wound?

He is recovering, and planning to go to Tashkent.

Rejoice, oh Isaiah!

Я не хочу и не могу иметь от вас ничего скрьтного.

Граф Вронский едет в Ташкент и желал бь проститься с нами.

Я сказала, что не хочу его принять.

I can’t and I don’t want to have any secrets from you.

Count Vronsky is leaving for Tashkent, and he would like to say goodbye to us.

I said I could not see him.

Я так люблю Анну и уважаю вас, что позволю себе дать совет — примите его.

Вронский — олицетворенная честь, и он уезжает в Ташкент…

Благодарю вас, княгиня, за участие и советь.

I love Anna and respect you so much that I venture to offer advice: do receive him.

Vronsky is the soul of honour, and he’s leaving for Tashkent…

Thank you, Princess, for your sympathy and advice.

А всё-таки ему левую. — Перестань.

Ромео из Ташкента загрустил, Джульетта в «Кукурузнике» умчалась.

Товарищ лейтенант, перестань пошлить.

Well, he’s got your left hand.

Our Romeo from Tashkent is sulking. His Juliet left in a biplane.

Lieutenant, stop being cheap.

В какую сторону мне плыть?

Я иммигрант из Ташкента и я заблудился.

Путь долог…

Which is the right direction?

Because I’m an immigrant from Tashkent and I lost my way

The way is long …

Бёрк — его так зовут?

25 лет назад, моя страна продала американцам, «Аннека Оил», права на строительство нефтепровода из Ташкента

Цена была абсурдной.

Burke? That’s his name?

Almost 25 years ago, my country sold an American company Anneca Oil, the rights to build a pipeline through Tashkent to Andijan region.

The price was absurd.

Думаю, ты найдешь самую занятную на сегодня историю на странице 20, в левом углу.

«По данным узбекских властей, отец Александр Набиев, местный священник из Ташкента, Узбекистан…»

Ты заинтригован, похищением священника?

Then let’s work. I think you’ll find today’s most intriguing story on page 20, bottom-left corner.

«According to Uzbek authorities, Father Aleksandr Nabiyev a local priest in the Tashkent region of Uzbekistan…»

You’re intrigued because a priest was kidnapped?

— У вас карандаш и бумага под рукой есть?

Пишите: на Казанский вокзал поездом Ташкент

— Москва прибыл дедушка.

— Do you have a pencil and a paper over there? — What pencil?

— Write down: a grandpa has arrived on Kazansky railway station.

He was on the train Tashkent — Moscow.

Чегой-то они?

Из Ташкента. Трясло их там…

Землетрясение, слыхала?

— From Tashkent.

— They were quaked there.

Have you heard of earthquakes?

Хуже всего если покалечат.

Я в Ташкенте в госпитале был, там пацаны лежат.

Палата целая.

The worst thing if you get crippled

When I was in Tashkent, I went to that hospital, and some

The whole ward

Всё ночью зубами скрипел. В атаку ходил.Спать никому не давал. Потом его куда-то отвезли.

в ташкент что ль в госпиталь, да?

Ага.

Been screaming whole night long, going to a combat ,no one could sleep

Then they took him to the hospital To Tashkent I guess

Aha

Совсем скоро.

Дела Ташкент, пап, мам Ташкент?

-Красноярск, Сибирь. -Оу, холодно.

Very soon

Business Tashkent? Papa, mama Tashkent?

Krasnoyarsk, Siberia, Oh, cold

Вертушка прилетит, к себе заберет.

В Ташкент.

Там хорошо. Тепло.

The choppers will take us

To Tashkent

There is good, warm.

Где намечена встреча?

Во вторник Ахмедов прибывает в Ташкент.

48 часами позже у него заказан обратный вылет.

Where’s the meet?

Ahmedov arrives in Tashkent on Tuesday.

He’s booked an outbound flight 48 hours later.

Спасибо вам, господин.

…в войсковой части в Ташкенте.

В Ташкенте?

Thank you, sir.

In the garrison in Tashkent.

Tashkent? But…

…в войсковой части в Ташкенте.

В Ташкенте?

Я бы предпочел остаться в Петербурге, сударь. Если Вы не возражаете.

In the garrison in Tashkent.

Tashkent? But…

I would like to stay in Peter, sir, if you don’t mind.

Я могу сделать лучше.

Сегодня вечером я отказался писать в Ташкент.

Я могу поменять решение, и Вы больше не увидите меня никогда.

I can do better than that.

Tonight I refused a posting to Tashkent.

I can change my mind, and you’ll never see me again.

Конечно

Ты хочешь, чтобы я уехал в Ташкент?

Тогда я еду в Ташкент.

Of course.

Do you want me to go to Tashkent?

So I’ll go to Tashkent.

Ты хочешь, чтобы я уехал в Ташкент?

Тогда я еду в Ташкент.

Нет!

Do you want me to go to Tashkent?

So I’ll go to Tashkent.

No!

Пойду, найду ее.

Кадры с камеры наблюдения из отеля Майкла в Ташкенте.

Это…

I’ll go find her.

Frame grabs from Michael’s hotel in Tashkent.

Is that…

Она думает только о себе, Майкл.

Ты должен понимать это лучше, чем кто-либо после того, что произошло в Ташкенте.

До нас только сейчас доходит.

She’s all about herself, Michael.

You should know that better than anybody after what happened in Tashkent.

And we are just getting this.

Вы и ваш муж купили в прошлом году

«Натуры Ташкента» Келли Ванг, да?

Это была картина или скульптура?

You and your husband bought

Kelly Vang’s «Tashkent Exteriors» last year, didn’t you?

Hmm, was that a painting or a sculpture?

Показать еще

Перевод «ташкент» на английский

Ваш текст переведен частично.

Вы можете переводить не более 999 символов за один раз.

Войдите или зарегистрируйтесь бесплатно на PROMT.One и переводите еще больше!

<>

Ташкент

м.р.

существительное

Склонение

Tashkent

Дата и место подписания: 03.02.2000 г., Ташкент.

Signature date and place: 03.02.2000, Tashkent.

Контексты

Дата и место подписания: 03.02.2000 г., Ташкент.

Signature date and place: 03.02.2000, Tashkent.

23 июня Владимир Путин прибыл в Ташкент на заседание Шанхайской организации сотрудничества.

On June 23, Vladimir Putin arrived to Tashkent for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit.

Первой столицей Узбекской ССР был город Самарканд, а с 1928 года столицей стал город Ташкент.

The first capital of the Uzbek SSR was Samarkand, replaced by Tashkent from 1928.

26 января 2005 года в ГУИН МВД (г. Ташкент) проведена встреча по вопросам борьбы с распространением ВИЧ/СПИДа в Центральной Азии с MHO » Counterpart International «.

On 26 January 2005, a meeting was held in the Central Penal Correction Department in Tashkent to discuss issues relating to HIV/AIDS control in Central Asia with the non-governmental organization Counterpart International.

Международные правозащитные организации в страну не пускают, она неоднократно отказывала во въезде докладчикам ООН, и Ташкент не разрешает спокойно работать в Узбекистане даже Международному Красному Кресту.

International human rights organizations are kept out; the country has repeatedly refused to allow visits from U.N. rapporteurs, and Tashkent won’t even allow the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to operate normally.

Бесплатный переводчик онлайн с русского на английский

Вам нужно переводить на английский сообщения в чатах, письма бизнес-партнерам и в службы поддержки онлайн-магазинов или домашнее задание? PROMT.One мгновенно переведет с русского на английский и еще на 20+ языков.

Точный переводчик

С помощью PROMT.One наслаждайтесь точным переводом с русского на английский, а также смотрите английскую транскрипцию, произношение и варианты переводов слов с примерами употребления в предложениях. Бесплатный онлайн-переводчик PROMT.One — достойная альтернатива Google Translate и другим сервисам, предоставляющим перевод с английского на русский и с русского на английский. Переводите в браузере на персональных компьютерах, ноутбуках, на мобильных устройствах или установите мобильное приложение Переводчик PROMT.One для iOS и Android.

Нужно больше языков?

PROMT.One бесплатно переводит онлайн с русского на азербайджанский, арабский, греческий, иврит, испанский, итальянский, казахский, китайский, корейский, немецкий, португальский, татарский, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, украинский, финский, французский, эстонский и японский.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

Перевод «ташкент» на английский

Tashkent

Uzbekistan

Tuscany

Toshkent

Столица узбекистана, ташкент («каменный город»), тяжело перенесла хх век: в результате землетрясения и революции было уничтожено большое количество памятников архитектуры, хотя сегодня выделяются средства, чтобы сделать центр города привлекательным и современным.

The capital of Uzbekistan, Tashkent («Stone City»), suffered a hard XX century: the earthquake and the Revolution destroyed a large number of architectural monuments, but today provides funds to make the city center attractive and modern.

В самых ранних китайских источниках ташкент фигурирует как ши, чжэши и юэни, в раннем средневековье — чач, шаш и джач.

In the earliest, Chinese sources Tashkent appears as SHi, CHzhemi and JUeni, in the early Middle Ages — CHach, SHashi Dzhach.

в как году ташкент стал столицей

In 1930, Tashkent became the capital.

Поэтому политическое давление на Ташкент невозможно.

That is why the political pressure on Tashkent is not possible.

Столица страны Ташкент быстро становится современным развитым международным мегаполисом.

The capital of the country Tashkent is rapidly becoming a modern developed, international mega polis.

В 1966-м отправился восстанавливать Ташкент после землетрясения.

In 1966, Tashkent began to rebuild after the tragic earthquake.

Однако после смены президента, Ташкент изменил свою политику на более открытую и дружелюбную.

However, after the change of the president, Tashkent changed its policy to a more open and friendly.

Также мы ждем несколько крупных визитов в Ташкент.

We are also waiting for several major visits to Tashkent.

При этом Ташкент, очевидно, имеет и политические амбиции.

At the same time, Tashkent, obviously, has political ambitions.

Однако постепенно название Ташкент вытесняет все остальные.

However, the name Tashkent gradually ousts all other names.

Ташкент — город с многовековой историей — сегодня претерпевает значительные экономические изменения.

Tashkent — a city with a long history — today is undergoing significant economic changes.

Для них Ташкент представлял важный пункт как источник доходов.

Tashkent represented for them an important point as an income source.

Территориально корпус университета расположен в городе Ташкент.

Territorially the university building is located in the city of Tashkent.

Город Ташкент представлен на фотографиях разными гранями своего прекрасного облика.

The city of Tashkent is presented in the photographs in the many facets of its beauty.

Ташкент отличает удивительно гармоничное сочетание национальных особенностей архитектуры с чертами современного города.

Tashkent is distinguished by surprisingly harmonious combination of national peculiarities of architecture with the features of a modern city.

Ташкент ставит вопрос о гарантиях для своей промышленности и других секторов экономики.

Tashkent raises the issue of guarantees for its industry and other sectors of its economy.

Работал дизайнером до 2007 года. (Ташкент).

He worked as a designer until 2007. (Tashkent).

В этих условиях Ташкент будет вынужден обратиться за экстренной военной помощью.

In such circumstances, Tashkent will have to ask for urgent military aid.

Как отмечается в хронике этой катастрофы, Ташкент первым принял сведения о землетрясении.

As it is noted in the chronicle of this accident, Tashkent was the first to accept data on earthquake.

Сохраняя свой исторический облик, Ташкент постоянно обновляется.

Retaining its historical appearance, Tashkent is being continuously renovated.

Результатов: 3024. Точных совпадений: 3024. Затраченное время: 63 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200